Lesson One - Culture

1.2 Elements of Culture

Making Connections: Policy & Debate

Is Canada Bilingual?

In the 1960s it became clear that the federal government needed to develop a bilingual language policy to integrate French Canadians into the national identity and prevent their further alienation. The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1965) recommended establishing official bilingualism within the federal government. As a result, the Official Languages Act became law in 1969 and established both English and French as the official languages of the federal government and federal institutions such as the courts. The Trudeau governments of the late 1960s and early 1970s had an even broader ambition to make Canada itself bilingual. Not only would Canadians be able to access government services in either French or English, no matter where they were in the country, but also French or English education. The entire country would be home for both French or English speakers (McRoberts 1997).

However, in the 1971 census, 67 percent of Canadians spoke English most often at home, while only 26 percent spoke French at home and most of these were in Quebec. Approximately 13 percent of Canadians could maintain a conversation in both languages (Statistics Canada 2007). Outside Quebec, the highest proportion of French spoken at home was 31.4 percent in New Brunswick. The next highest were Ontario at 4.6 percent and Manitoba at 4 percent. In British Columbia, only 0.5 percent of the population spoke French at home. French speakers had widely settled Canada, but French speaking outside Quebec had lost ground since Confederation because of the higher rates of anglophone immigrants, the assimilation of francophones, and the lack of French-speaking institutions outside Quebec (McRoberts 1997). It seemed even in 1971 that the ideal of creating a bilingual nation was unlikely and unrealistic.

What has happened to the concept of bilingualism over the last 40 years? According to the 2011 census, 58 percent of the Canadian population spoke English at home, while only 18.2 percent spoke French at home. Proportionately the number of both English and French speakers has actually decreased since the introduction of the Official Languages Act in 1969. On the other hand, the number of people who can maintain a conversation in both official languages has increased to 17.5 percent from 13 percent (Statistics Canada 2007). However, the most significant linguistic change in Canada has not been French-English bilingualism, but the growth in the use of languages other than French and English. In a sense, what has happened is that the shifting cultural composition of Canada has rendered the goal of a bilingual nation anachronistic.

|

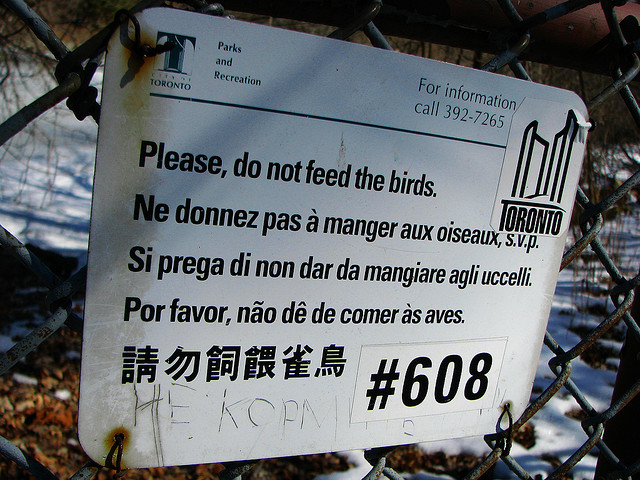

Nowadays, many signs—on streets and in stores—are multilingual. |

Today it would be more accurate to speak of Canada as a multilingual nation. One-fifth of Canadians speak a language other than French or English at home; 11.5 percent report speaking English and a language other than French, and 1.3 percent report speaking French and a language other than English. In Toronto, 32.2 percent of the population speak a language other than French and English at home; 8.8 percent of whom speak Cantonese, 8 percent Punjabi, 7 percent an unspecified dialect of Chinese, 5.9 percent Urdu, and 5.7 percent Tamil. In Greater Vancouver, 31 percent of the population speak a language other than French and English at home; 17.7 percent of whom speak Punjabi, followed by Cantonese (16.0 percent), unspecified Chinese (12.2 percent), Mandarin (11.8 percent), and Philippine Tagalog (6.7 percent).

Today, the government of Canada still conducts its business in both official languages. French and English are the dominant languages in the workplace and school. Labels on products are required to be in both French and English. But increasingly a lot of product information is available in in multiple languages. In Vancouver and Toronto, and to a lesser extent Montreal, linguistic diversity has become increasingly prevalent. French and English are still the central languages of convergence and integration for immigrant communities who speak other languages—only 1.8 percent of the population were unable to conduct a conversation in either English or French in 2011—but increasingly Canada is linguistically diverse rather than bilingual.