Lesson Two - Social Inequality in Canada

2.4 Theoretical Perspective on Social Inequality

Basketball is one of the highest-paying professional sports. There is stratification even among teams. For example, the Minnesota Timberwolves hand out the lowest annual payroll, while the Los Angeles Lakers reportedly pay the highest. Kobe Bryant, a Lakers shooting guard who retired in 2016, was one of the highest paid athletes in the NBA, earning around $25 million a year (Basketballreference.com, 2011). Even within specific fields, layers are stratified and members are ranked.

In sociology, even an issue such as NBA salaries can be seen from various points of view. Functionalists will examine the purpose of such high salaries, while critical sociologists will study the exorbitant salaries as an unfair distribution of money. Social stratification takes on new meanings when it is examined from different sociological perspectives — functionalism, critical sociology, and interpretive sociology.

Functionalism

In sociology, the functionalist perspective examines how society’s parts operate. According to functionalism, different aspects of society exist because they serve a needed purpose. What is the function of social stratification?

In 1945, sociologists Kingsley Davis (1908-1997) and Wilbert Moore (1914-1987) published the Davis-Moore thesis, which argued that the greater the functional importance of a social role, the greater must be the reward. The theory posits that social stratification represents the inherently unequal value of different work. Certain tasks in society are more valuable than others. Qualified people who fill those positions must be rewarded more than others.

According to Davis and Moore, a firefighter’s job is more important than, for instance, a grocery store cashier’s job. The cashier position does not require the same skill and training level as firefighting. Without the incentive of higher pay and better benefits, why would someone be willing to rush into burning buildings? If pay levels were the same, the firefighter might as well work as a grocery store cashier. Davis and Moore believed that rewarding more important work with higher levels of income, prestige, and power encourages people to work harder and longer.

Davis and Moore stated that, in most cases, the degree of skill required for a job determines that job’s importance. They also stated that the more skill required for a job, the fewer qualified people there would be to do that job. Certain jobs, such as cleaning hallways or answering phones, do not require much skill. The employees don’t need a college degree. Other work, like designing a highway system or delivering a baby, requires immense skill.

In 1953, Melvin Tumin (1919-1994) countered the Davis-Moore thesis in Some Principles of Stratification: A Critical Analysis. Tumin questioned what determined a job’s degree of importance. The Davis-Moore thesis does not explain, he argued, why a media personality with little education, skill, or talent becomes famous and rich on a reality show or a campaign trail. The thesis also does not explain inequalities in the education system, or inequalities due to race or gender. Tumin believed social stratification prevented qualified people from attempting to fill roles (1953). For example, an underprivileged youth has less chance of becoming a scientist, no matter how smart he or she is, because of the relative lack of opportunity available.

The Davis-Moore thesis, though open for debate, was an early attempt to explain why stratification exists. The thesis states that social stratification is necessary to promote excellence, productivity, and efficiency, thus giving people something to strive for. Davis and Moore believed that the system serves society as a whole because it allows everyone to benefit to a certain extent.

Critical Sociology

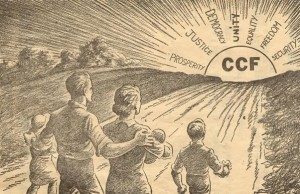

“Towards the Dawn,” a 1930s promotional poster for the Saskatchewan Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) [Long Description] (Image courtesy of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation/ Wikimedia Commons)

Critical sociologists are deeply critical of social inequality, asserting that it benefits only some people not all of society. For instance, to a critical sociologist it seems problematic that after a long period of increasing equality of incomes from World War II to the 1970s, the wealthiest 1 percent of income earners have been increasing their share of the total income of Canadians from 7.7 percent in 1977 to 13.8 percent in 2007 (Yalnizyan, 2010). In 1982, the median income earner in the top 1 percent of incomes earned seven times more than the median income earner in the other 99 percent. In 2010, the median income earner in the top 1 percent earned ten times more. Moreover, while the median income for the top 1 percent increased from $191,600 to $283,000 in constant dollars (i.e., adjusted for inflation), the median income for the bottom 99 percent only increased from $28,000 to $28,400 (Statistics Canada, 2013). Canada’s richest 1 percent took almost a third (32 percent) of all growth in incomes 2007 (Yalnizyan, 2010).

Critical sociologists view this “great U-turn” in income equality over the 20th and 21st centuries as a product of both the ability of corporate elites to grant themselves huge salary and bonus increases and the shift toward neoliberal public policy and tax cuts. Rather than creating conditions in which wealth trickles down, tax cuts and neoliberal policies tremendously benefit the rich at the expense of the poor. This is an example of the way that stratification perpetuates inequality. Contrary to the analysis of functionalists, huge corporate bonuses continued to be awarded even when dysfunctional corporate and financial mismanagement of the economy led to the global financial crisis of 2008. Nor is it the case that corporate elites work harder to merit more rewards. Over the period of increasing inequality in income, the only group not working more weeks and hours in the paid workforce is the richest 10 percent of families (Yalnizyan, 2007).

Critical sociologists try to bring awareness to inequalities, such as how a rich society can have so many poor members. Many critical sociologists draw on the work of Karl Marx. During the 19th-century era of industrialization, Marx analyzed the way the owning class or capitalists raked in profits and got rich, while working-class proletarians earned skimpy wages and struggled to survive. With such opposing interests, the two groups were divided by differences of wealth and power. Marx saw workers experience deep exploitation, alienation, and misery resulting from class power (Marx, 1848). He also predicted that the growing collective impoverishment of the working class would lead them, through the leadership of unions, to recognize their common class interests. A common class “consciousness” uniting different types of labour would lead to the revolutionary conditions whereby the working class could throw off their “fetters” and overthrow the capitalists. With the abolition of private property (i.e., productive property) and collective ownership of the means of production, Marx imagined that class conflict could be ended forever. A “communist” society that abolished the private ownership of the means of production would be a true democracy. Marx did not live see the state socialist systems in the Soviet Union and elsewhere that called themselves communist but ended up replacing capitalist-based inequality with bureaucratic-based inequality.

Today, while working conditions have improved, critical sociologists believe that the strained working relationship between employers and employees still exists. Capitalists own the means of production, and a neoliberal political system is in place to make business owners rich and keep workers poor. Moreover, the privileged position of the middle classes has been steadily eroded by growing inequalities of wealth and income. Some sociologists argue that the middle class is becoming proletarianized, meaning that in terms of income, property, control over working conditions, and overall life chances, the middle class is becoming more and more indistinguishable from the wage-earning working class (Abercrombie & Urry, 1983). Nevertheless, according to critical sociologists, increasing social inequality is neither inevitable nor necessary.

Interpretive Sociology

Within interpretive sociology, symbolic interactionism is a theory that uses everyday interactions of individuals to explain society as a whole. Symbolic interactionism examines stratification from a micro-level perspective. This analysis strives to explain how people’s social standing affects their everyday interactions.

In most communities, people interact primarily with others who share the same social standing. It is precisely because of social stratification that people tend to live, work, and associate with others like themselves, people who share their same income level, educational background, or racial background, and even tastes in food, music, and clothing. The built-in system of social stratification groups people together.

Symbolic interactionists also note that people’s appearance reflects their perceived social standing. Housing, clothing, and transportation indicate social status, as do hairstyles, taste in accessories, and personal style. Pierre Bourdieu’s (1930-2002) concept of cultural capital suggests that cultural “assets” such as education and taste are accumulated and passed down between generations in the same manner as financial capital or wealth (1984). This marks individuals from an early age by such things as knowing how to wear a suit or having an educated manner of speaking. In fact the children of parents with a postsecondary degree are 60 percent likely to attend university themselves, while the children of parents with less than a high school education have only a 32 percent chance of attending university (Shaienks & Gluszynski, 2007).

Cultural capital is capital also in the sense of an investment, as it is expensive and difficult to attain while providing access to better occupations. Bourdieu argued that the privilege accorded to those who hold cultural capital is a means of reproducing the power of the ruling classes. People with the “wrong” cultural attributes have difficulty attaining the same privileged status. Cultural capital becomes a key measure of distinction between social strata.

Imelda Marcos, the wife of the Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos, was reputed to be one of the ten wealthiest woman in the world in 1975. When her husband was deposed in 1986, the couple fled leaving behind 2,000 to 3,000 shoes from world renowned designers Ferragamo, Givenchy, Chanel, and Christian Dior. (Image courtesy of Vince Lamb/Flickr)

In the Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929) described the activity of conspicuous consumption as the tendency of people to buy things as a display of status rather than out of need. Conspicuous consumption refers to buying certain products to make a social statement about status. Carrying pricey but eco-friendly water bottles could indicate a person’s social standing. Some people buy expensive trendy sneakers even though they will never wear them to jog or play sports. A $17,000 car provides transportation as easily as a $100,000 vehicle, but the luxury car makes a social statement that the less-expensive car can’t live up to. All of these symbols of stratification are worthy of examination by interpretive sociologists because their social significance is determined by the shared meanings they hold.