Lesson One - Population, Urbanization, and the Environment

1.2 Urbanization

Figure 20.7. The towers of Vancouver are an iconic image of city life. (Photo courtesy of Magnus Larsson/flickr)

Urbanization is the study of the social, political, and economic relationships in cities, and someone specializing in urban sociology would study those relationships. In some ways, cities can be microcosms of universal human behaviour, while in others they provide a unique environment that yields their own brand of human behaviour. There is no strict dividing line between rural and urban; rather, there is a continuum where one bleeds into the other. However, once a geographically concentrated population has reached approximately 100,000 people, it typically behaves like a city regardless of what its designation might be.

The Growth of Cities

According to sociologist Gideon Sjoberg (1965), there are three prerequisites for the development of a city. First, good environment with fresh water and a favourable climate; second, advanced technology, which will produce a food surplus to support non-farmers; and third, strong social organization to ensure social stability and a stable economy. Most scholars agree that the first cities were developed somewhere in ancient Mesopotamia, though there are disagreements about exactly where. Most early cities were small by today’s standards, and the largest city around 100 CE was most likely Rome, with about 650,000 inhabitants (Chandler and Fox 1974). The factors limiting the size of ancient cities included lack of adequate sewage control, limited food supply, and immigration restrictions. For example, serfs were tied to the land, and transportation was limited and inefficient. Today, the primary influence on cities’ growth is economic forces.

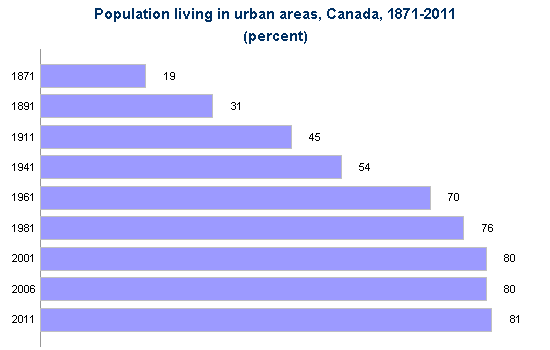

Figure 20.8. As this chart illustrates, the shift from rural to urban living in Canada has been dramatic and continuous. (Graph courtesy of Employment and Social Development Canada 2014). This reproduction is a copy of the version available at http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=34. The Government of Canada allows reproduction of this graph in whole or in part for non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, (http://www.esdc.gc.ca/eng/terms/index.shtml).

Urbanization in Canada

Urbanization in Canada proceeded rapidly during the Industrial Era of 1870 to 1920. The percentage of Canadians living in cities went from 19 percent in 1871 to 49 percent in 1920 (Statistics Canada 2011). As more and more opportunities for work appeared in factories, workers left farms (and the rural communities that housed them) to move to the cities. Urban development in Canada in this period focused on Montreal and Toronto, which were the two major hubs of transportation, commerce, and industrial production in the country. These cities began to take on a modern industrial urban form with tall office towers downtown and a vast spatial expansion of suburbs surrounding them.

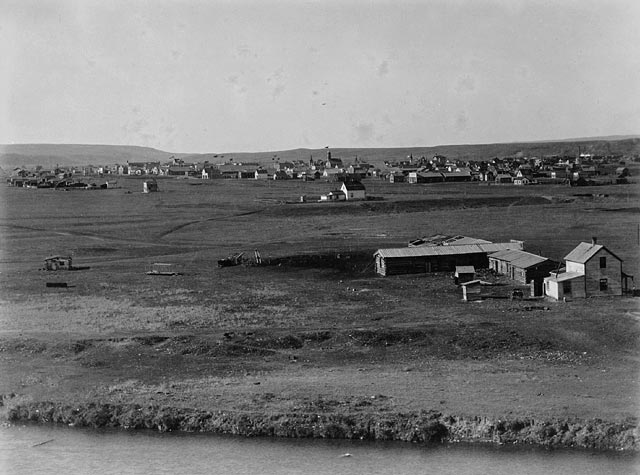

Figure 20.9. Calgary in 1885. Montreal and Toronto were Canada’s major urban centres for most of the 19th and early 20th centuries. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Following the Industrial Era, urbanization in Canada from the 1940s onward took the form of the corporate city. Stelter (1986) describes the corporate city as being more focused economically on corporate management and financial (and other related professional) services than industrial production. Five features define the form of corporate cities: dispersal of population in suburbs, high-rise apartment buildings, isolated industrial parks, downtown cores of office towers, and suburban shopping malls. This development was made possible by the reorientation of the city to automobile and truck use, deindustrialization and the rise of the service and knowledge economy, and a spatial decentralization of the population.

Finally we might note the transformation of the corporate city into a postmodern city form. Postmodern cities are defined by their orientation to circuits of global consumption, the fragmentation of previously homogeneous urban cultures, and the emergence of multiple centres or cores. John Hannigan (1998) describes three related developments that characterize the postmodern city: the edge city, dual city, and fantasy city formations. Edge cities are urban areas in suburbs or residential areas that have no central core or clear boundaries but form around clusters of shopping malls, entertainment complexes, and office towers at major transportation intersections. Dual cities are cities that are divided into wealthy, high-tech, information-based zones of urban development and poorer, run-down, marginalized zones of urban underdevelopment and informal economic activity. Mike Davis (1990) used the term “fortress city” to describe the way that cities abandon the commitment to creating viable public spaces and universal access to urban resources in favour of the privatization of public spaces, a “militarization” of private and public security services, and the creation of exclusive gated communities for the wealthy and middle classes. Fantasy cities are cities that choose to transform themselves into Disneyland-like “theme parks” or sites of mega-events (like the Olympics or FIFA World Cup competitions) to draw international tourists. Victoria, B.C., for example, has branded itself as a safe, historical—“more English than the English”—heritage destination for cruise ship and other types of tourism.

Suburbs and Exurbs

As cities grew more crowded, and often more impoverished and costly, more and more people began to migrate back out of them. But instead of returning to rural small towns (like they had resided in before moving to the city), these people needed close access to the cities for their jobs. In the 1850s, as the urban population greatly expanded and transportation options improved, suburbs developed. Suburbs are the communities surrounding cities, typically close enough for a daily commute in, but far enough away to allow for more space than city living affords. The bucolic suburban landscape of the early 20th century has largely disappeared due to sprawl. Suburban sprawl contributes to traffic congestion, which in turn contributes to commuting time. Commuting times and distances have continued to increase as new suburbs developed farther and farther from city centres. Simultaneously, this dynamic contributed to an exponential increase in natural resource use, like petroleum, which sequentially increased pollution in the form of carbon emissions.

As the suburbs became more crowded and lost their charm, those who could afford it turned to the exurbs, communities that exist outside the ring of suburbs and are typically populated by even wealthier families who want more space and have the resources to lengthen their commute. It is interesting to note that unlike U.S. cities, Canadian cities have always retained a fairly large elite residential presence in enclaves around the city centres, a pattern that has been augmented in recent decades by patterns of inner-city resettlement by elites (Caulfield 1994; Keil and Kipfer 2003). As cities evolve from industrial to postindustrial, this practice of gentrification becomes more common. Gentrification refers to members of the middle and upper classes entering city areas that have been historically less affluent and renovating properties while the poor urban underclass are forced by resulting price pressures to leave those neighbourhoods. This practice is widespread and the lower class is pushed into increasingly decaying portions of the city.

Together, the city centres, suburbs, exurbs, and metropolitan areas all combine to form a metropolis. New York was the first North American megalopolis, a huge urban corridor encompassing multiple cities and their surrounding suburbs. The Toronto-Hamilton-Oshawa, Vancouver-Abbotsford-Chilliwack, and Calgary-Edmonton corridors are similar megalopolis formations. These metropolises use vast quantities of natural resources and are a growing part of the North American landscape.

Figure 20.10. The suburban sprawl in Toronto means long commutes and traffic congestion. (Photo courtesy of Payon Chung/flickr)

Urbanization around the World

As was the case in North America, other urban centres experienced a growth spurt during the Industrial Era. In 1800, the only city in the world with a population over 1 million was Beijing, but by 1900, there were 16 cities with a population over 1 million (United Nations 2008). The development of factories brought people from rural to urban areas, and new technology increased the efficiency of transportation, food production, and food preservation. For example, from the mid-1670s to the early 1900s, London increased its population from 550,000 to 7 million (Old Bailey Proceedings Online 2011). The growth in global urbanization in the 20th and 21st centuries is following the blueprint of North American cities, but is occurring much more quickly and at larger scales, especially in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries. Shanghai almost tripled its population from 7.8 million to 20.2 million between 1990 and 2011, adding the equivalent of the population of New York City in 20 years. It is projected to reach 28.4 million by 2025, third in size behind Tokyo (38.7 million) and New Delhi (32.9 million) (United Nations 2012).

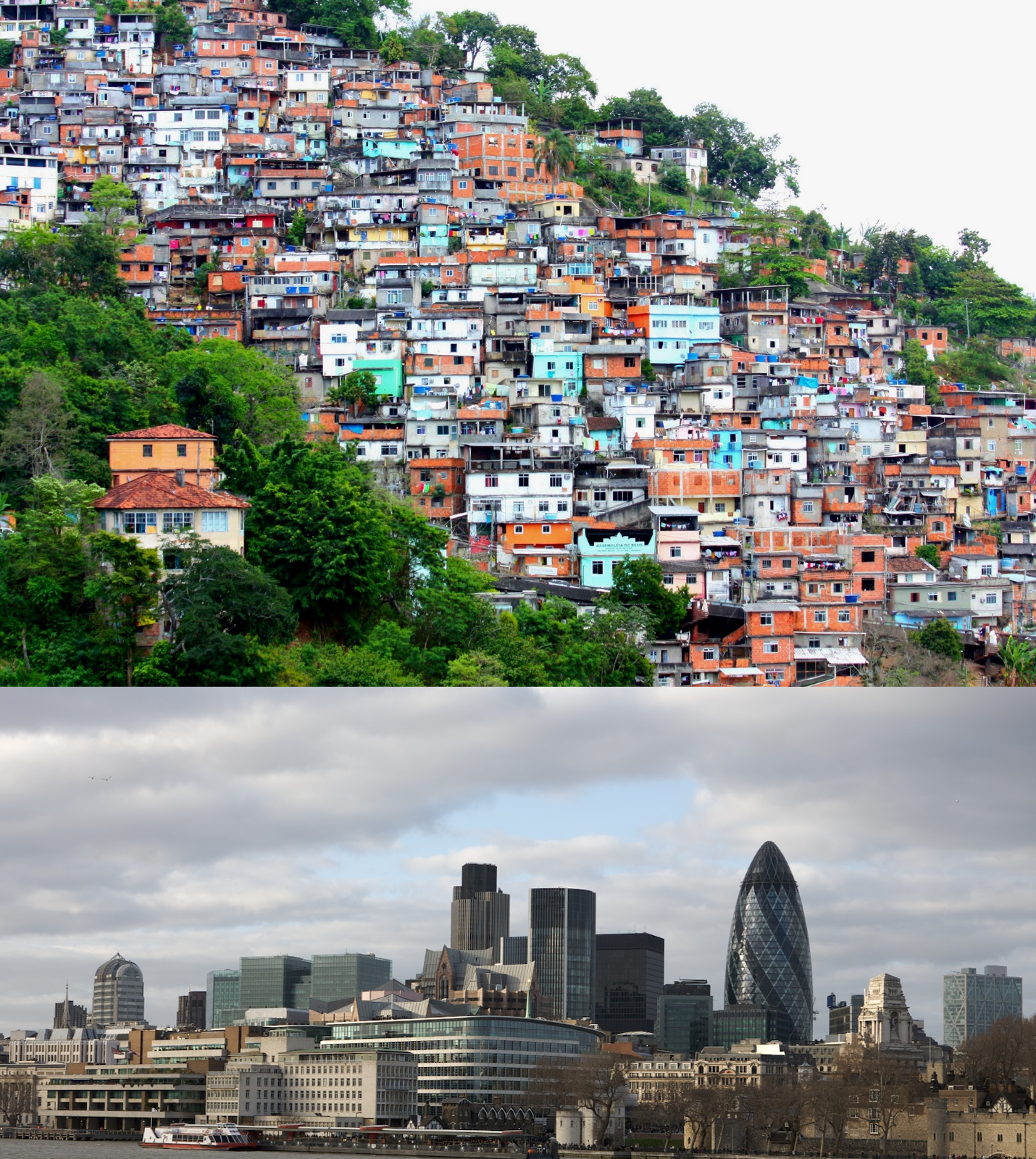

Global urbanization reached the 50 percent mark in 2008, meaning that more than half of the global population was living in cities compared to only 30 percent 50 years ago (United Nations 2008). Global urbanization has been uneven between core countries and the rest of the world, however. Two developments might serve to illustrate some of the stark differences in the global experience of urbanization: the formation of slum cities and global cities.

Figure 20.11. The slum city and the global city: the Favéla Morro do Prazères in Rio de Janeiro and the London financial district show two sides of global urbanization (Photos courtesy of dany13/Flickr and Peter Pearson/Flickr)

Slum cities refer to the development on the outskirts of cities of unplanned shantytowns or squats with no access to clean water, sanitation, or other municipal services. These slums exist largely outside the rule of law and have become centres for child labour, prostitution, criminal activities, and struggles between gangs and paramilitary forces for control. Mike Davis (2006) estimates that there are 200,000 slum cities worldwide including Quarantina in Beirut, the Favéla in Rio de Janeiro, the “City of the Dead” in Cairo, and Santa Cruz Meyehualco in Mexico City. He notes that while slum residents constitute only 6 percent of the urban population in developed countries, they constitute 78.2 percent of city dwellers in semi-peripheral countries. In Davis’s analysis, neoliberal restructuring and the Structural Adjustment Programs of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are largely responsible for the creation of the informal economy and the withdrawal of the state from urban planning and the provision of services. As a result, slum cities have become the blueprint for urban development in the developing world.

On the other side of the phenomenon of global urbanization are global cities like London, New York, and Tokyo. Saskia Sassen (2001) describes the global city as a unique development based on the new role of cities in the circuits of global information and global capital circulation and accumulation. Global cities become centres for financial and corporate services, providing a technical and information infrastructure and a pool of human resources (skills, professional and technical services, consulting services, etc.) to service the increasingly complex operations of global corporations. As such, they are progressively detached, economically and socially, from their local and national political-geographic contexts. They become instead nodes in a global network of informational, economic, and financial transactions or flows. It becomes possible in this sense to say that New York is closer to Tokyo and London in terms of the number of direct transactions between them than it is to Philadelphia or Baltimore.

Sassen (2005) emphasizes three important tendencies that develop from the formation of global cities: a concentration of wealth in the corporate sectors of these cities, a growing disconnection between the cities and their immediate geographic regions, and the development of a large marginalized population that is excluded from the job market for these high-end activities. The increasing number of global cities:

- Host the headquarters of multinational corporations, such as Coca-Cola

- Exercise significant international political influence, such as that from Beijing or Berlin

- Host the headquarters of international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as the United Nations

- Host influential media, such as the BBC and Al Jazeera

- Host advanced communication and transportation infrastructure, such as that in Shanghai (Sassen 2001)

Theoretical Perspectives on Urbanization

As the examples above illustrate, the issues of urbanization play significant roles in the study of sociology. Race, economics, and human behaviour intersect in cities. We can look at urbanization through the sociological perspectives of functionalism and conflict theory. Functional perspectives on urbanization focus generally on the ecology of the city, while conflict perspective tends to focus on political economy.

Human ecology is a functionalist field of study that focuses on the relationship between people and their built and natural physical environments (Park 1915). According to this Chicago School approach, urban land use and urban population distribution occurs in a predictable pattern once we understand how people relate to their living environment. For example, in Canada, we have a transportation system geared to accommodate individuals and families in the form of interprovincial highways built for cars. In contrast, most parts of Europe emphasize public transportation such as high-speed rail and commuter lines, as well as walking and bicycling. The challenge for a human ecologist working in Canadian urban planning would be to design landscapes and waterscapes with natural beauty, while also figuring out how to provide for free-flowing transport of innumerable vehicles—not to mention parking!

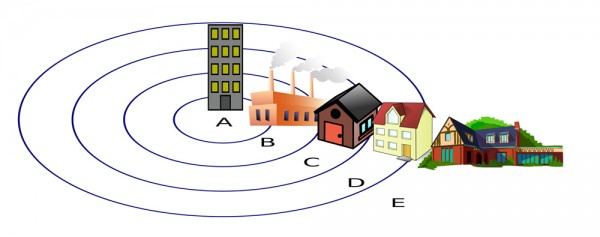

The concentric zone model (Burgess 1925) is perhaps the most famous example of human ecology. This model views a city as a series of concentric circular areas, expanding outward from the centre of the city, with various “zones” invading (new categories of people and businesses overrun the edges of nearby zones) and succeeding adjacent zones(after invasion, the new inhabitants repurpose the areas they have invaded and push out the previous inhabitants). In this model, Zone A, in the heart of the city, is the centre of the business and cultural district. Zone B, the concentric circle surrounding the city centre, is composed of formerly wealthy homes split into cheap apartments for new immigrant populations; this zone also houses small manufacturers, pawn shops, and other marginal businesses. Zone C consists of the homes of the working class and established ethnic enclaves. Zone D consists of wealthy homes, white-collar workers, and shopping centres. Zone E contains the estates of the upper class (exurbs) and the suburbs.

Figure 20.12. This illustration depicts the concentric zones that make up a city. (Photo courtesy of Zeimusu/Wikimedia Commons)

In contrast to the functionalist approach, the critical perspective focuses on the dynamics of power and influence in the shaping of the city. One way to do this is to examine how urban areas change according to specific decisions made by political and economic leaders. Cities are not so much the product of a quasi-natural “ecological” unfolding of social differentiation and succession, but of a dynamic of capital investment and disinvestment. City space is acted on primarily as a commodity that is bought and sold for profit. The dynamics of city development are better understood therefore as products of what Logan and Molotch (1987) call “growth coalitions”—coalitions of politicians, real estate investors, corporations, property owners, urban planners, architects, sports teams, cultural institutions, etc.—who work together to attract private capital to the city and lobby government for subsidies and tax breaks for investors. These coalitions generally benefit business interests and the middle and upper classes while marginalizing the interests of working and lower classes.

For example, sociologists Feagin and Parker (1990) suggested three aspects to understanding how political and economic leaders control urban growth. First, economic and political leaders work alongside each other to effect change in urban growth and decline, determining where money flows and how land use is regulated. Second, exchange value and use value are balanced to favour the middle and upper classes so that, for example, public land in poor neighbourhoods may be rezoned for use as industrial land. Finally, urban development is dependent on both structure (groups such as local government) and agency (individuals including business people and activists), and these groups engage in a push-pull dynamic that determines where and how land is actually used. For example, NIMBY (not in my backyard) movements are more likely to emerge in middle- and upper-class neighbourhoods, so these groups have more control over the usage of local land.