Lesson Two - Socialization

2.3 Agents of Socialization

Socialization helps people learn to function successfully in their social worlds. How does the process of socialization occur? How do we learn to use the objects of our society’s material culture? How do we come to adopt the beliefs, values, and norms that represent its nonmaterial culture? This learning takes place through interaction with various agents of socialization, like peer groups and families, plus both formal and informal social institutions.

Social Group Agents

Social groups often provide the first experiences of socialization. Families, and later peer groups, communicate expectations and reinforce norms. People first learn to use the tangible objects of material culture in these settings, as well as being introduced to the beliefs and values of society.

Family

Family is the first agent of socialization. Mothers and fathers, siblings and grandparents, plus members of an extended family, all teach a child what he or she needs to know. For example, they show the child how to use objects (such as clothes, computers, eating utensils, books, bikes); how to relate to others (some as “family,” others as “friends,” still others as “strangers” or “teachers” or “neighbours”); and how the world works (what is “real” and what is “imagined”). As you are aware, either from your own experience as a child or your role in helping to raise one, socialization involves teaching and learning about an unending array of objects and ideas.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that families do not socialize children in a vacuum. Many social factors impact how a family raises its children. For example, we can use sociological imagination to recognize that individual behaviours are affected by the historical period in which they take place. Sixty years ago, it would not have been considered especially strict for a father to hit his son with a wooden spoon or a belt if he misbehaved, but today that same action might be considered child abuse.

Sociologists recognize that race, social class, religion, and other societal factors play an important role in socialization. For example, poor families usually emphasize obedience and conformity when raising their children, while wealthy families emphasize judgment and creativity (National Opinion Research Center 2008). This may be because working-class parents have less education and more repetitive-task jobs for which the ability to follow rules and to conform helps. Wealthy parents tend to have better educations and often work in managerial positions or in careers that require creative problem solving, so they teach their children behaviours that would be beneficial in these positions. This means that children are effectively socialized and raised to take the types of jobs that their parents already have, thus reproducing the class system (Kohn 1977). Likewise, children are socialized to abide by gender norms, perceptions of race, and class-related behaviours.

In Sweden, for instance, stay-at-home fathers are an accepted part of the social landscape. A government policy provides subsidized time off work—68 weeks for families with newborns at 80 percent of regular earnings—with the option of 52 of those weeks of paid leave being shared between both mothers and fathers, and eight weeks each in addition allocated for the father and the mother. This encourages fathers to spend at least eight weeks at home with their newborns (Marshall 2008). As one stay-at-home dad says, being home to take care of his baby son “is a real fatherly thing to do. I think that’s very masculine” (Associated Press 2011). Overall 90 percent of men participate in the paid leave program. In Canada on the other hand, outside of Quebec, parents can share 35 weeks of paid parental leave at 55 percent of their regular earnings. Only 10 percent of men participate. In Quebec, however, where in addition to 32 weeks of shared parental leave, men also receive five weeks of paid leave, the participation rate of men is 48 percent. In Canada overall, the participation of men in paid parental leave increased from 3 percent in 2000 to 20 percent in 2006 because of the change in law in 2001 that extended the number of combined paid weeks parents could take. Researchers note that a father’s involvement in child raising has a positive effect on the parents’ relationship, the father’s personal growth, and the social, emotional, physical and cognitive development of children (Marshall 2008). How will this effect differ in Sweden and Canada as a result of the different nature of their paternal leave policies?

Figure 5.5. The socialized roles of dads (and moms) vary by society. (Photo courtesy of Nate Grigg/flickr)

Peer Groups

A peer group is made up of people who are similar in age and social status and who share interests. Peer group socialization begins in the earliest years, such as when kids on a playground teach younger children the norms about taking turns or the rules of a game or how to shoot a basket. As children grow into teenagers, this process continues. Peer groups are important to adolescents in a new way, as they begin to develop an identity separate from their parents and exert independence. Additionally, peer groups provide their own opportunities for socialization since kids usually engage in different types of activities with their peers than they do with their families. Peer groups provide adolescents’ first major socialization experience outside the realm of their families. Interestingly, studies have shown that although friendships rank high in adolescents’ priorities, this is balanced by parental influence.

Institutional Agents

The social institutions of our culture also inform our socialization. Formal institutions—like schools, workplaces, and the government—teach people how to behave in and navigate these systems. Other institutions, like the media, contribute to socialization by inundating us with messages about norms and expectations.

School

Most Canadian children spend about seven hours a day, 180 days a year, in school, which makes it hard to deny the importance school has on their socialization. In elementary and junior high, compulsory education amounts to over 8,000 hours in the classroom (OECD 2013). Students are not only in school to study math, reading, science, and other subjects—the manifest function of this system. Schools also serve a latent function in society by socializing children into behaviours like teamwork, following a schedule, and using textbooks.

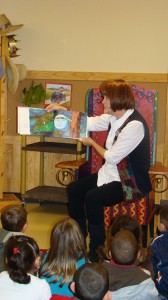

Figure 5.6. These kindergarteners aren’t just learning to read and write, they are being socialized to norms like keeping their hands to themselves, standing in line, and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. (Photo courtesy of Bonner Springs Library/flickr)

School and classroom rituals, led by teachers serving as role models and leaders, regularly reinforce what society expects from children. Sociologists describe this aspect of schools as the hidden curriculum, the informal teaching done by schools.

For example, in North America, schools have built a sense of competition into the way grades are awarded and the way teachers evaluate students. Students learn to evaluate themselves within a hierarchical system as “A,” “B,” “C,” etc. students (Bowles and Gintis 1976). However, different “lessons” can be taught by different instructional techniques. When children participate in a relay race or a math contest, they learn that there are winners and losers in society. When children are required to work together on a project, they practise teamwork with other people in cooperative situations. Bowles and Gintis argue that the hidden curriculum prepares children for a life of conformity in the adult world. Children learn how to deal with bureaucracy, rules, expectations, waiting their turn, and sitting still for hours during the day. The latent functions of competition, teamwork, classroom discipline, time awareness and dealing with bureaucracy are features of the hidden curriculum.

Schools also socialize children by teaching them overtly about citizenship and nationalism. In the United States, children are taught to say the Pledge of Allegiance. Most districts require classes about U.S. history and geography. In Canada, on the other hand, critics complain that students do not learn enough about national history, which undermines the development of a sense of shared national identity (Granatstein 1998). Textbooks in Canada are also continually scrutinized and revised to update attitudes toward the different cultures in Canada as well as perspectives on historical events; thus, children are socialized to a different national or world history than earlier textbooks may have done. For example, information about the mistreatment of First Nations more accurately reflects those events than in textbooks of the past. In this regard, schools educate students explicitly about aspects of citizenship important for being able to participate in a modern, heterogeneous culture.

The Workplace

Just as children spend much of their day at school, most Canadian adults at some point invest a significant amount of time at a place of employment. Although socialized into their culture since birth, workers require new socialization into a workplace, both in terms of material culture (such as how to operate the copy machine) and nonmaterial culture (such as whether it is okay to speak directly to the boss or how the refrigerator is shared).

Different jobs require different types of socialization. In the past, many people worked a single job until retirement. Today, the trend is to switch jobs at least once a decade. Between the ages of 18 and 44, the average baby boomer of the younger set held 11 different jobs (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010). This means that people must become socialized to, and socialized by, a variety of work environments.

Religion

While some religions may tend toward being an informal institution, this section focuses on practices related to formal institutions. Religion is an important avenue of socialization for many people. Canada is full of synagogues, temples, churches, mosques, and similar religious communities where people gather to worship and learn. Like other institutions, these places teach participants how to interact with the religion’s material culture (like a mezuzah, a prayer rug, or a communion wafer). For some people, important ceremonies related to family structure—like marriage and birth—are connected to religious celebrations. Many of these institutions uphold gender norms and contribute to their enforcement through socialization. From ceremonial rites of passage that reinforce the family unit, to power dynamics which reinforce gender roles, religion fosters a shared set of socialized values that are passed on through society.

Government

Although we do not think about it, many of the rites of passage people go through today are based on age norms established by the government. To be defined as an “adult” usually means being 18 years old, the age at which a person becomes legally responsible for themselves. And 65 is the start of “old age” since most people become eligible for senior benefits at that point.

Each time we embark on one of these new categories—senior, adult, taxpayer—we must be socialized into this new role. Seniors, for example, must learn the ropes of obtaining pension benefits. This government program marks the points at which we require socialization into a new category.

Mass Media

Mass media refers to the distribution of impersonal information to a wide audience, via television, newspapers, radio, and the internet. With the average person spending over four hours a day in front of the TV (and children averaging even more screen time), media greatly influences social norms (Roberts, Foehr, and Rideout 2005). People learn about objects of material culture (like new technology and transportation options), as well as nonmaterial culture—what is true (beliefs), what is important (values), and what is expected (norms).