Lesson One - Groups and Organizations

1.3 Formal Organizations

A complaint of modern life is that society is dominated by large and impersonal secondary organizations. From schools to businesses to health care to government, these organizations are referred to as formal organizations. A formal organization is a large secondary group deliberately organized to achieve its goals efficiently. Typically, formal organizations are highly bureaucratized. The term bureaucracy refers to what Max Weber termed “an ideal type” of formal organization (1922). In its sociological usage, “ideal” does not mean “best”; it refers to a general model that describes a collection of characteristics, or a type that could describe most examples of the item under discussion. For example, if your professor were to tell the class to picture a car in their minds, most students will picture a car that shares a set of characteristics: four wheels, a windshield, and so on. Everyone’s car will be somewhat different, however. Some might picture a two-door sports car while others might picture an SUV. It is possible for a car to have three wheels instead of four. However, the general idea of the car that everyone shares is the ideal type. Bureaucracies are similar. While each bureaucracy has its own idiosyncratic features, the way each is deliberately organized to achieve its goals efficiently shares a certain consistency. We will discuss bureaucracies as an ideal type of organization.

Types of Formal Organizations

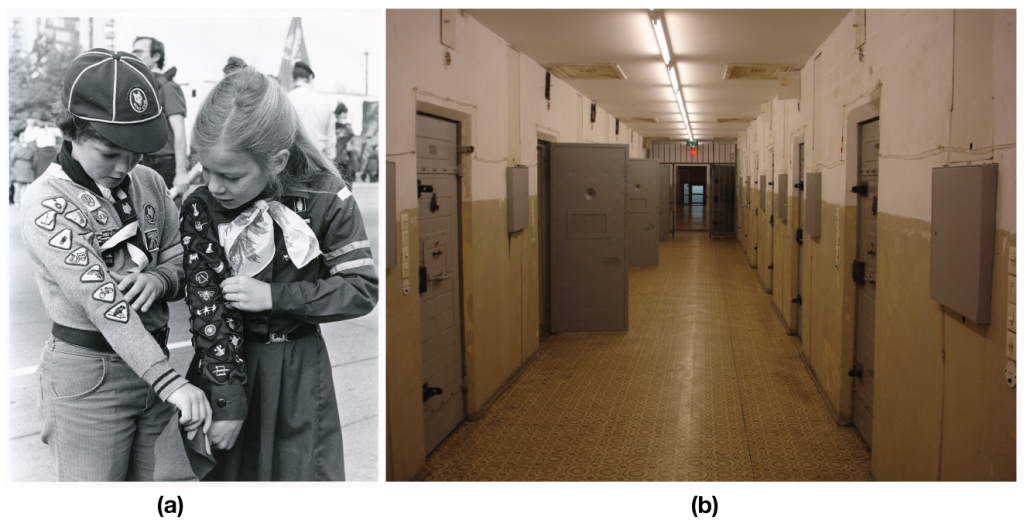

Figure 6.10. Cub and Guide troops and correctional facilities are both formal organizations. (Photo (a) courtesy of Paul Hourigan/Hamilton Spectator 1983; Photo (b) courtesy of CxOxS/flickr)

Sociologist Amitai Etzioni (1975) posited that formal organizations fall into three categories. Normative organizations, also called voluntary organizations, are based on shared interests. As the name suggests, joining them is voluntary and typically done because people find membership rewarding in an intangible way. Compliance to the group is maintained through moral control. The Audubon Society or a ski club are examples of normative organizations. Coercive organizations are groups that one must be coerced, or pushed, to join. These may include prison, the military, or a rehabilitation centre. Compliance is maintained through force and coercion. Goffman (1961) states that most coercive organizations are total institutions. A total institution is one in which inmates live a controlled life apart from the rest of society and in which total resocialization takes place. The third type are utilitarian organizations, which, as the name suggests, are joined because of the need for a specific material reward. High school or a workplace would fall into this category—one joined in pursuit of a diploma, the other in order to make money. Compliance is maintained through remuneration and rewards.

Table 6.1. Etzioni’s Three Types of Formal Organizations (Source: Etzioni 1975)

| Normative or Voluntary | Coercive | Utilitarian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit of Membership | Non-material benefit | Corrective or disciplinary benefit | Material benefit |

| Type of Membership | Volunteer basis | Obligatory basis | Contractual basis |

| Feeling of Connectedness | Shared affinity | Coerced affinity | Pragmatic affinity |

Bureaucracies

Bureaucracies are an ideal type of formal organization. Pioneer sociologist Max Weber (1922) popularly characterized a bureaucracy as having a hierarchy of authority, a clear division of labour, explicit rules, and impersonality. Bureaucracies were the basic structure of rational efficient organization, yet people often complain about bureaucracies, declaring them slow, rule-bound, difficult to navigate, and unfriendly. Let us take a look at terms that define bureaucracy as an ideal type of formal organization to understand what they mean.

Hierarchy of authority refers to the aspect of bureaucracy that places one individual or office in charge of another, who in turn must answer to her own superiors. For example, if you are an employee at Walmart, your shift manager assigns you tasks. Your shift manager answers to the store manager, who must answer to the regional manager, and so on in a chain of command up to the CEO who must answer to the board members, who in turn answer to the stockholders. There is a clear chain of authority that enables the organization to make and comply with decisions.

A clear division of labour refers to the fact that within a bureaucracy, each individual has a specialized task to perform. For example, psychology professors teach psychology, but they do not attempt to provide students with financial aid forms. In this case, it is a clear and commonsensical division. But what about in a restaurant where food is backed up in the kitchen and a hostess is standing nearby texting on her phone? Her job is to seat customers, not to deliver food. Is this a smart division of labour?

The existence of explicit rules refers to the way in which rules are outlined, written down, and standardized. There is a continuous organization of official functions bound by rules. For example, at your college or university, student guidelines are contained within the student handbook. As technology changes and campuses encounter new concerns like cyberbullying, identity theft, and other issues, organizations are scrambling to ensure their explicit rules cover these emerging topics.

Bureaucracies are also characterized by impersonality, which takes personal feelings out of professional situations. Each office or position exists independently of its incumbent, and clients and workers receive equal treatment. This characteristic grew, to some extent, out of a desire to eliminate the potential for nepotism, backroom deals, and other types of “irrational” favouritism, simultaneously protecting customers and others served by the organization. Impersonality is an attempt by large formal organizations to protect their members. However, the result is often that personal experience is disregarded. For example, you may be late for work because your car broke down, but the manager at Pizza Hut doesn’t care why you are late, only that you are late.

Finally, bureaucracies are, in theory at least, meritocracies, meaning that hiring and promotion are based on proven and documented skills, rather than on nepotism or random choice. In order to get into graduate school, you need to have an impressive transcript. In order to become a lawyer and represent clients, you must graduate from law school and pass the provincial bar exam. Of course, there is a popular image of bureaucracies that they reward conformity and sycophancy rather than skill or merit. How well do you think established meritocracies identify talent? Wealthy families hire tutors, interview coaches, test-prep services, and consultants to help their children get into the best schools. This starts as early as kindergarten in New York City, where competition for the most highly regarded schools is especially fierce. Are these schools, many of which have copious scholarship funds that are intended to make the school more democratic, really offering all applicants a fair shake?

There are several positive aspects of bureaucracies. They are intended to improve efficiency, ensure equal opportunities, and increase efficiency. And there are times when rigid hierarchies are needed. However, there is a clear component of irrationality within the rational organization of bureaucracies. Firstly, bureaucracies create conditions of bureaucratic alienation in which workers cannot find meaning in the repetitive, standardized nature of the tasks they are obliged to perform. As Max Weber put it, the “individual bureaucrat cannot squirm out of the apparatus in which he is harnessed… He is only a single cog in an ever‐moving mechanism which prescribes to him an essentially fixed route of march” (1922). Secondly, bureaucracies can lead to bureaucratic inefficiency and ritualism (red tape). They can focus on rules and regulations to the point of undermining the organization’s goals and purpose. Thirdly, bureaucracies have a tendency toward inertia. You may have heard the expression “trying to turn a tanker around mid-ocean,” which refers to the difficulties of changing direction with something large and set in its ways. Inertia means bureaucracies focus on perpetuating themselves rather than effectively accomplishing or re-evaluating the tasks they were designed to achieve. Finally, as Robert Michels (1911) suggested, bureaucracies are characterized by the iron law of oligarchy in which the organization is ruled by a few elites. The organization serves to promote the self-interest of oligarchs and insulate them from the needs of the public or clients.

Remember that many of our bureaucracies grew large at the same time that our school model was developed—during the Industrial Revolution. Young workers were trained and organizations were built for mass production, assembly-line work, and factory jobs. In these scenarios, a clear chain of command was critical. Now, in the information age, this kind of rigid training and adherence to protocol can actually decrease both productivity and efficiency. Today’s workplace requires a faster pace, more problem solving, and a flexible approach to work. Too much adherence to explicit rules and a division of labour can leave an organization behind. Unfortunately, once established, bureaucracies can take on a life of their own. As Max Weber said, “Once it is established, bureaucracy is among those social structures which are the hardest to destroy” (1922).

Figure 6.11. This McDonald’s storefront in Egypt shows the McDonaldization of society. (Photo courtesy of s_w_ellis/flickr)

The McDonaldization of Society

The McDonaldization of society (Ritzer 1994) refers to the increasing presence of the fast-food business model in common social institutions. This business model includes efficiency (the division of labour), predictability, calculability, and control (monitoring). For example, in your average chain grocery store, people at the cash register check out customers while stockers keep the shelves full of goods, and deli workers slice meats and cheese to order (efficiency). Whenever you enter a store within that grocery chain, you receive the same type of goods, see the same store organization, and find the same brands at the same prices (predictability). You will find that goods are sold by the kilogram, so that you can weigh your fruit and vegetable purchases rather than simply guessing at the price for that bag of onions, while the employees use a time card to calculate their hours and receive overtime pay (calculability). Finally, you will notice that all store employees are wearing a uniform (and usually a name tag) so that they can be easily identified. There are security cameras to monitor the store, and some parts of the store, such as the stockroom, are generally considered off-limits to customers (control).

While McDonaldization has resulted in improved profits and an increased availability of various goods and services to more people worldwide, it has also reduced the variety of goods available in the marketplace while rendering available products uniform, generic, and bland. Think of the difference between a mass-produced shoe and one made by a local cobbler, between a chicken from a family-owned farm versus a corporate grower, or a cup of coffee from the local roaster instead of one from a coffee-shop chain. Ritzer also notes that the rational systems, as efficient as they are, are irrational in that they become more important than the people working within them, or the clients being served by them. “Most specifically, irrationality means that rational systems are unreasonable systems. By that I mean that they deny the basic humanity, the human reason, of the people who work within or are served by them.” (Ritzer 1994)