Lesson Four - Education

4.1 Education Around the World

Figure 16.2. These children are at a library in Singapore, where students are outperforming North American students on worldwide tests. (Photo courtesy of kodomut/flickr)

Education is a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. Every nation in the world is equipped with some form of education system, though those systems vary greatly. The major factors affecting education systems are the resources and money that are utilized to support those systems in different nations. As you might expect, a country’s wealth has much to do with the amount of money spent on education. Countries that do not have such basic amenities as running water are unable to support robust education systems or, in many cases, any formal schooling at all. The result of this worldwide educational inequality is a social concern for many countries, including Canada.

International differences in education systems are not solely a financial issue. The value placed on education, the amount of time devoted to it, and the distribution of education within a country also play a role in those differences. For example, students in South Korea spend 220 days a year in school, compared to the 190 days (180 days in Quebec) a year of their Canadian counterparts. Canadian students between the ages of 7 and 14 spend an average of 7,363 hours in compulsory education compared to an average of 6,710 hours for all member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Statistics Canada 2012). As of 2012, Canada ranked first among OECD countries in the proportion of adults aged 25 to 64 with post-secondary education (51 percent). Canada ranked first with students with a college education (24 percent) and eighth in the proportion of adults with a university education (26 percent). However, with respect to post-secondary educational attainment of 25- to 34-year-olds, Canada falls into 15th place as post-secondary education attainment rates in countries like South Korea and Ireland have been surpassing Canada by a large margin in recent years (OECD 2013).

Then there is the issue of educational distribution within a nation. In December 2010, the results of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) tests, which are administered to 15-year-old students worldwide, were released. Those results showed that students in Canada performed well in reading skills (5th out of 65 countries), math (8th out of 65 countries), and science (7th out of 65 countries) (Knighton, Brochu, and Gluszynski 2010). Students at the top of the rankings hailed from Shanghai, Finland, Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. The United States on the other hand was 17th in reading skills and had fallen from 15th to 25th in the rankings for science and math (National Public Radio 2010).

Analysts determined that the nations and city-states at the top of the rankings had several things in common. For one, they had well-established standards for education with clear goals for all students. They also recruited teachers from the top 5 to 10 percent of university graduates each year, which is not the case for most countries (National Public Radio 2010).

Finally, there is the issue of social factors. One analyst from the OECD, the organization that created the test, attributed 20 percent of performance differences and the United States’ low rankings to differences in social background. Canadian students’ average scores were high over all but were also highly equitable, meaning that the difference in performance between high scorers and low scorers was relatively low (Knighton, Brochu, and Gluszynski 2010). This suggests that differences in educational expenditure between jurisdictions and in the socioeconomic background of students are not so great as to create large gaps in performance. However, in the United States, researchers noted that educational resources, including money and quality teachers, are not distributed equitably. In the top-ranking countries, limited access to resources did not necessarily predict low performance. Analysts also noted what they described as “resilient students,” or those students who achieve at a higher level than one might expect given their social background. In Shanghai and Singapore, the proportion of resilient students is about 70 percent. In the United States, it is below 30 percent. These insights suggest that the United States’ educational system may be on a descending path that could detrimentally affect the country’s economy and its social landscape (National Public Radio 2010).

Formal and Informal Education

As already mentioned, education is not solely concerned with the basic academic concepts that a student learns in the classroom. Societies also educate their children, outside of the school system, in matters of everyday practical living. These two types of learning are referred to as formal education and informal education.

Formal education describes the learning of academic facts and concepts through a formal curriculum. Arising from the tutelage of ancient Greek thinkers, centuries of scholars have examined topics through formalized methods of learning. Three hundred years ago few people knew how to read and write. Education was available only to the higher classes; they had the means to access scholarly materials, plus the luxury of leisure time that could be used for learning. The rise of capitalism and its accompanying social changes made education more important to the economy and therefore more accessible to the general population. Around 1900, Canada and the United States were the first countries to come close to the ideal of universal participation of children in school. The idea of universal mass education is therefore a relatively recent idea, one that is still not achieved in many parts of the world.

The modern Canadian educational system is the result of this progressive expansion of education. Today, basic education is considered a right and responsibility for all citizens. Expectations of this system focus on formal education, with curricula and testing designed to ensure that students learn the facts and concepts that society believes are basic knowledge.

In contrast, informal education describes learning about cultural values, norms, and expected behaviours by participating in a society. This type of learning occurs both through the formal education system and at home. Our earliest learning experiences generally happen via parents, relatives, and others in our community. Through informal education, we learn how to dress for different occasions, how to perform regular life routines like shopping for and preparing food, and how to keep our bodies clean.

Figure 16.4. Parents teaching their children to cook provide an informal education. (Photo courtesy of eyeliam/flickr)

Cultural transmission refers to the way people come to learn the values, beliefs, and social norms of their culture. Both informal and formal education include cultural transmission. For example, a student will learn about cultural aspects of modern history in a Canadian history classroom. In that same classroom, the student might learn the cultural norm for asking a classmate out on a date through passing notes and whispered conversations.

Access to Education

Another global concern in education is universal access. This term refers to people’s equal ability to participate in an education system. On a world level, access might be more difficult for certain groups based on race, class, or gender (as was the case in Canada earlier in our nation’s history, a dynamic we still struggle to overcome). The modern idea of universal access arose in Canada as a concern for people with disabilities. In Canada, one way in which universal education is supported is through provincial governments covering the cost of free public education. Of course, the way this plays out in terms of school budgets and taxes makes this an often-contested topic on the national, provincial, and community levels.

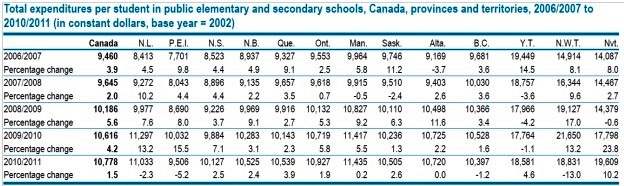

Table 16.1. Per student spending varies by province and territory. (Table courtesy of Statistics Canada)

Although school boards across the country had attempted to accommodate children with special needs in their educational systems through a variety of means from the 19th century on, it was not until the implementation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 that the question of universal access to education for disabled children was seen in terms of a Charter right (Siegel and Ladyman 2000). Many provincial jurisdictions implemented educational policy to integrate special needs students into the classroom with mainstream students. For example, policy in British Columbia was revised in the mid-1990s to include specific measures to define students with special needs, develop individual education plans, and find school placements for students with special needs (Siegel and Ladyman 2000). In Ontario, Bill 82 was passed in 1980, establishing five principles for special education programs and services for special needs students: Universal access, education at public expense, an appeal process, ongoing identification and continuous assessment, and appropriate programming (Morgan 2003).

Today, the optimal way to include differently able students in standard classrooms is still being researched and debated. “Inclusion” is a method that involves complete immersion in a standard classroom, whereas “mainstreaming” balances time in a special-needs classroom with standard classroom participation. There continues to be social debate surrounding how to implement the ideal of universal access to education.