Lesson Five - Race and Ethnicity

Overview

Figure 11.1. The Sikh turban or “Dastaar” is a required article in the observance of the Sikh faith. Baltej Singh Dhillon was the first Sikh member of the RCMP to wear a turban on active duty. This sparked a major controversy in 1990, but today people barely bat an eye when they see a police officer wearing a turban. Race and ethnicity are part of the human experience. How do the signs of racial and ethnic diversity play in a role in who we are and how we relate to one another? (Photo courtesy of Sanyam Bahga/Wikipedia)

Introduction to Race and Ethnicity

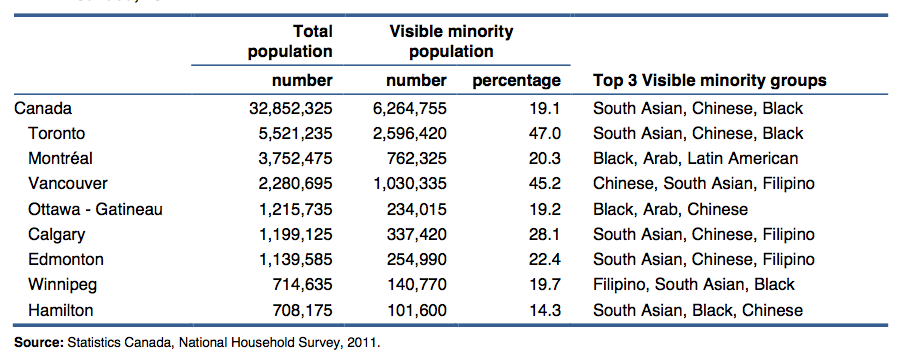

Visible minorities are defined as “persons, other than aboriginal persons, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour” (Statistics Canada 2013, p. 14). This is a contentious term, as we will see below, but it does give us a way to speak about the growing ethnic and racial diversity of Canada. The 2011 census noted that visible minorities made up 19.1 percent of the Canadian population, or almost one out of every five Canadians. This was up from 16.2 percent in the 2006 census (Statistics Canada 2013). The three largest visible minority groups were South Asians (25 percent), Chinese (21.1 percent), and blacks (15.1 percent).

Going back to the 1921 census, only 0.8 percent of population were made up of people of Asian origin, whereas 0.2 percent of the population were black. Aboriginal Canadians made up 1.3 percent of the population. The vast majority of the population were Caucasians (“whites”) of British or French ancestry. These figures did not change appreciably until after the changes to the Immigration Act in 1967, which replaced an immigration policy based on racial criteria with a point system based on educational and occupational qualifications (Li 1996). The 2011 census reported that 78 percent of the immigrants who arrived in Canada between 2006 and 2011 were visible minorities (Statistics Canada 2013).

Still, these figures do not really give a complete picture of racial and ethnic diversity in Canada. Ninety-six percent of visible minorities live in cities, mainly Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal, making these cities extremely diverse and cosmopolitan. In Vancouver, almost half the population (45.2 percent) is made up of visible minorities. Within Greater Vancouver, 70.4 percent of the residents of Richmond, 59.5 percent of the residents of Burnaby, and 52.6 of the residents of Surrey are visible minorities. In the Toronto area, where visible minorities make up 47 percent of the population, 72.3 percent of the residents of the suburb of Markham are visible minorities (Statistics Canada 2013). In many parts of urban Canada, it is a misnomer to use the term visible minority, as the “minorities” are now in the majority.

Table 11.1. Visible minority population and top three visible minority groups, selected census metropolitan areas, Canada, 2011. (Table courtesy of Statistics Canada, 2013). Source: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.pdf (p. 17)

Projecting forward based on current trends, Statistics Canada estimates that by 2031, between 29 and 32 percent of the Canadian population will be visible minorities. Visible minority groups will make up 63 percent of the population of Toronto and 59 percent of the population of Vancouver (Statistics Canada 2010). The outcome of these trends is that Canada has become a much more racially and ethnically diverse country over the 20th and 21st centuries. It will continue to become more diverse in the future.

In large part this has to do with immigration policy. Canada is a settler society, a society historically based on colonization through foreign settlement and displacement of aboriginal inhabitants, so immigration is the major influence on population diversity. In the two decades following World War II, Canada followed an immigration policy that was explicitly race based. Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s statement to the House of Commons in 1947 expressed this in what were, at the time, uncontroversial terms:

There will, I am sure, be general agreement with the view that the people of Canada do not wish, as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large-scale immigration from the orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population. Any considerable oriental immigration would, moreover, be certain to give rise to social and economic problems of a character that might lead to serious difficulties in the field of international relations. The government, therefore, has no thought of making any change in immigration regulations which would have consequences of the kind (cited in Li 1996 pp. 163-164).

Today this would be a completely unacceptable statement from a Canadian politician. Immigration is based on a non-racial point system. Canada defines itself as a multicultural nation that promotes and recognizes the diversity of its population. This does not mean, however, that Canada’s legacy of institutional and individual prejudice and racism has been erased. Nor does it mean that the problems of managing a diverse population have been resolved.

In 1997, the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination criticized the Canadian government for using the term “visible minority,” citing that distinctions based on race or colour are discriminatory (CBC 2007). The term combines a diverse group of people into one category whether they have anything in common or not. What does it actually mean to be a member of a visible minority in Canada? What does it mean to be a member of the “non-visible” majority? What do these terms mean in practice?