Lesson 2: Psychosocial Causes of Abnormal Behaviour

| Site: | MoodleHUB.ca 🍁 |

| Course: | Abnormal Psychology 35 RVS |

| Book: | Lesson 2: Psychosocial Causes of Abnormal Behaviour |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 30 October 2025, 1:14 AM |

Section/Lesson Objectives

The student will ...

• Understand and describe how Psychosocial Causes of Abnormal Behaviour interact to cause abnormal behaviour

• Determine the genetic syndrome a person has from evaluating his or her karyotype

• Describe what constitutional liabilities are and how they relate to mental illnesses

• Explain how nutrition affects mental health

• State how physical deprivation can negatively affect mental health

• Give examples of how psychosocial factors affect behaviour [This lesson]

• Describe the Johari window and apply it to different scenarios [This lesson]

• Discuss the effects of bullying [This lesson]

• Differentiate between the way various cultures view abnormalityy

• Understand and describe how sociocultural factors affect mental health

Introduction

Environment

Our genes influence our behaviour; there is no question about that. The environment we live in, however, also influences our behaviour – especially the environment we are subjected to as children. Psychosocial factors relate to environmental influences that make a person vulnerable to disorder or abnormal behaviour. These factors can be grouped as shown in Diagram 5.1 below.

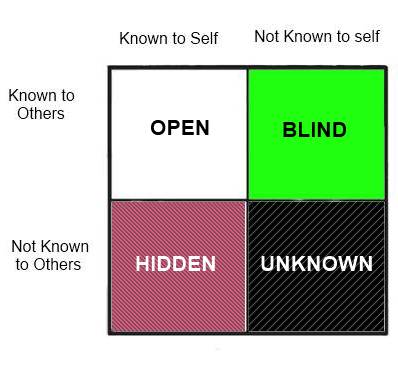

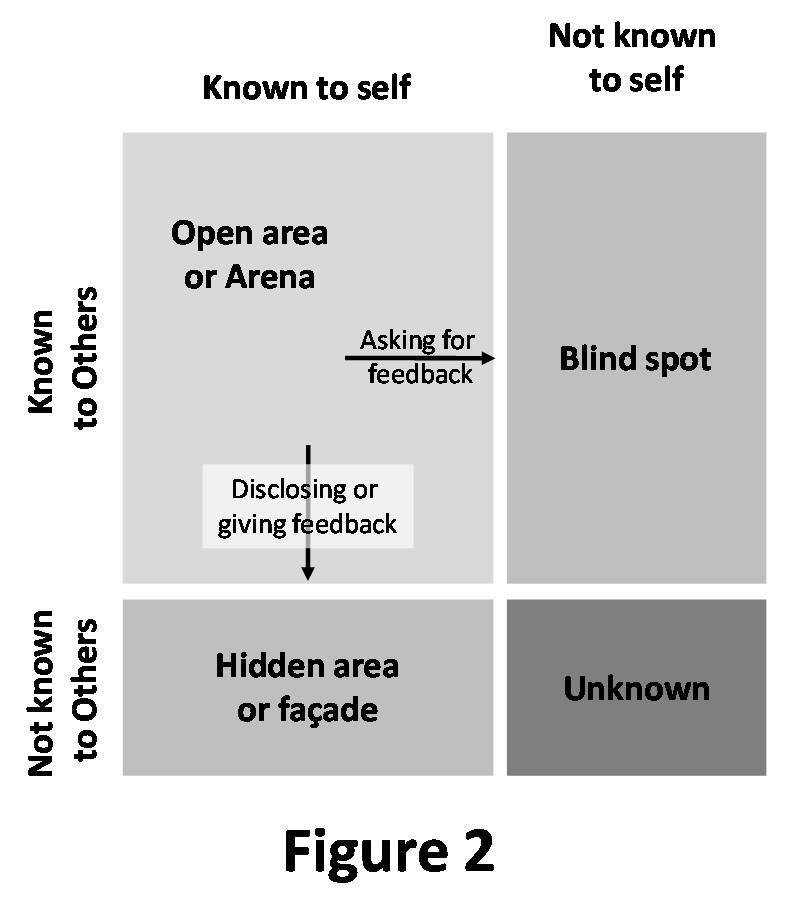

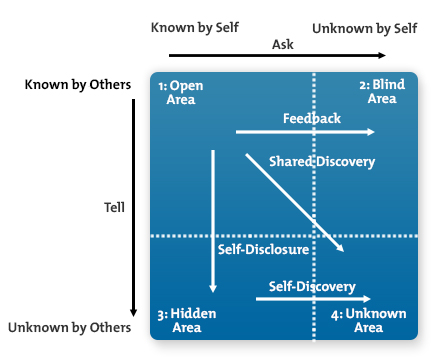

Self-perception

How we view the world, what we expect, believe, know, assume, and value are each a part of our self-perception. These same features can make us vulnerable to disordered behaviour. What other people believe and value, for example, may be different from our beliefs and values. What we show others regarding ourselves may not be what others receive or perceive. Two men, Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, developed a model to help people understand how their self-perception is presented to themselves and others. They termed this model the Johari Window. The model consists of a four-paned “window” as illustrated in Figure 1.1. The window divides personal awareness into four different areas as represented by its four quadrants: open, hidden, blind, and unknown. The lines dividing the four panes are like window shades. These shades can move as interaction between people progresses, thus effectively changing the size of each window.

Figure 1.1: Johari Window

The Johari Window

Figure 2.1: The Johari Window

The Open Self quadrant represents things that people know about themselves and that others also know about them. For example, most people know the name of their parents (as do the parents themselves). A person may even know his or her parents’ favourite music, food, or movies. In addition to facts and interests, the open window can include feelings, behaviours, wants, needs, and desires – in fact, any information that a person is willing to share.

The Open Self quadrant represents things that people know about themselves and that others also know about them. For example, most people know the name of their parents (as do the parents themselves). A person may even know his or her parents’ favourite music, food, or movies. In addition to facts and interests, the open window can include feelings, behaviours, wants, needs, and desires – in fact, any information that a person is willing to share.

When a person first meets someone new, the size of the open window or quadrant may be small. This may be due to personal preference about withholding information or a lack of time to exchange information. As the process of getting to know one another continues, the “window shades” may move down or to the right, placing more information into the open window.

The Blind Self quadrant represents things that someone knows about another person that the person is unaware of. For example, if your friend walks out of a public washroom and has toilet paper hanging from the back of his shoe, he may not know it. This information is in his blind quadrant because you can see it and but he cannot. If you tell your friend that he has toilet paper on his shoe, the window shade moves to the right enlarging the open quadrant’s area. This is an example of a simple issue. More complex issues may result in functional problems. For instance, people may not realize that they tend to avoid eye contact when interacting with authority figures. This could place them in awkward positions when developing trust relationships with employers, police officers, etc., especially in North America where the culture interprets avoidance of eye contact as suspicious.

The Hidden Self quadrant represents things that people know about themselves that they do not want others to know  about. For example, Charlie may not want to tell his friends that he is afraid of the dark. This information would be in his hidden quadrant. As soon as he tells his friends that he is afraid of the dark, he is moving the information from the hidden quadrant into the open quadrant.

about. For example, Charlie may not want to tell his friends that he is afraid of the dark. This information would be in his hidden quadrant. As soon as he tells his friends that he is afraid of the dark, he is moving the information from the hidden quadrant into the open quadrant.

The Unknown Self quadrant represents things that neither people know about themselves nor their friends know about them. For example, Maria may discuss with a friend a dream that she had. As they try to understand the meaning of the dream, a new awareness may become apparent, known to neither of them before the discussion. When people are placed in novel situations, they may learn information about themselves that they did not realize before. Sometimes this newfound knowledge is liberating or positive, and other times the information is debilitating or negative.

As a person’s level of confidence and self-esteem improves, he or she may ask for others to comment on his or her blind spots. A priest, for example, may seek feedback from his congregation on the quality of a particular sermon with the desire of improving his presentation. At other times, however, people may avoid sharing parts of themselves with others – the parts that would make them vulnerable.

Video: The Johari Window Model

Many people have subconscious beliefs and motivations that may reflect feelings of inadequacy, incompetence, impotence, unworthiness, rejection, guilt, dependency, etc. that may be difficult for them to confront consciously – any of which may be obvious to others. To help cope with subconscious feelings, people may employ a variety of defence mechanisms such as denial, projection, rationalization, regression, repression, and sublimation. Many people tend to cling to existing assumptions and reject or distort new information that is contradictory to their cognitive outlook. Changing one’s existing framework to incorporate conflicting information is a challenge. When a change does occur, this accommodation can be painful and time-consuming. If accommodation does not occur, however, a person may become vulnerable to disorder.

As children develop, they acquire various skills. They learn strategies for categorizing information, they employ coping mechanisms, and they develop preferences and dislikes -- many of which continue into their adult lives. The approach to life that children develop is further shaped during adulthood. How well children are able to integrate new information and learning styles affects their adult behaviour. In an ideal world, the environment of childhood through to adulthood should include the following:

a) Comprehension and/or understanding, order, and predictability. Unless we can see order and predictability in our environment, we cannot determine intelligent responses to events. The rules and customs of society reflect this need for order and understanding.

b) Adequacy, capability, and security. Adults and children alike need to feel that they are competent people. Feeling inadequate reduces coping ability and increases insecurity.

c) Love, belonging, and approval. All individuals need to love and be loved. Even if other basic needs are lacking (e.g., extreme poverty), a child raised in a loving home can overcome the deficiency of many things.

d) Self-esteem, worth, and uniqueness. Linked closely to adequacy, people need to feel worthy of respect from others.

e) Values, meaning, and hope. Feelings of futility and apathy may develop without a measure of value and meaning to life.

f) Personal growth and fulfillment. The ability to increase personal satisfaction by using skills, potential, and knowledge in creative ways influences our motivational structure and enhances physical and psychological well-being.

Self-motivation

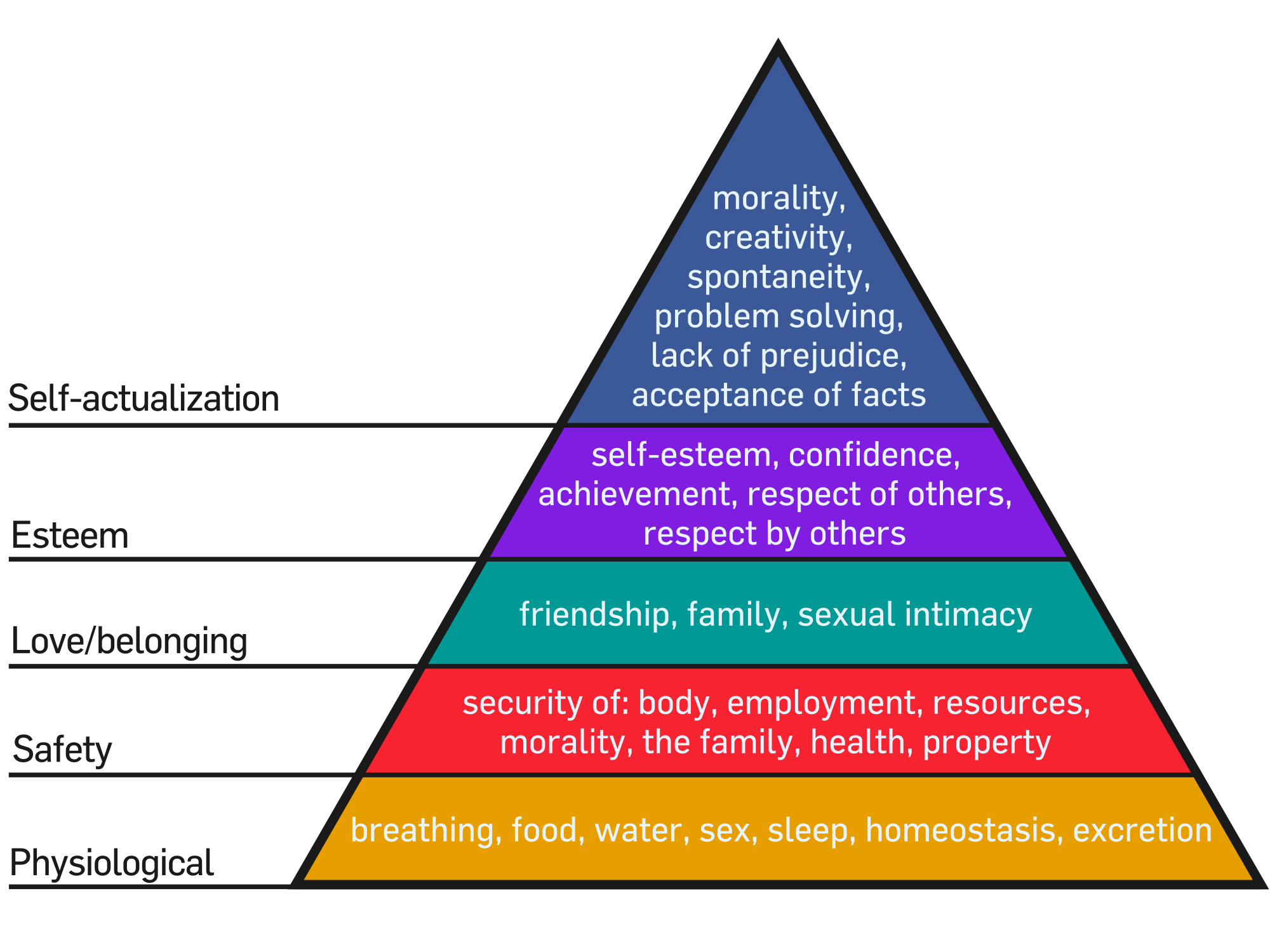

To survive, humans must be motivated to find food, obtain water, and seek shelter. These are basic biological survival requirements that almost all people are motivated to fulfill. What about people who are motivated to sky-dive or mountain climb? The majority of people are not motivated to fulfill these desires – they have a different motivation pattern. Also, with few people attaining a measure of self-actualization (the highest level on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs), one can conclude that many people are at less than maximum psychological adjustment, even if all their basic needs are met. People are often not aware of why they may be motivated to do things. Their unconscious thoughts direct them to activities that may fit with their view of reality even if they cannot state what these views are.

Hierarchy of Needs

One of Abraham Maslow’s most famous contributions to psychology was his hierarchy of human needs. Maslow believed that people needed to satisfy certain levels of needs in a certain order if they were to become the best people they could be.

The lower needs on his hierarchy are concerned mainly with physiological needs. The higher needs are associated with emotional states: happiness, peace of mind, and a rich inner life. Maslow believed that, before a person could move to a higher state, all the lower needs must be met. He also believed that the higher needs can be attained only in later life. Maslow’s hierarchy is illustrated in Figure 4.1

Figure 4.1: Hierarchy of Human Needs.

Physiological needs

Physiological needs are directly related to human survival. They include food, water, sex, and sleep. Maslow believed that if these needs were not properly met, a person would spend his or her life obsessed with them and would be unable to move to any higher stage in life. For example, if a woman is starving, she must spend all her time and energy finding enough food to keep her alive; she would have little opportunity to think about anything else.

Safety needs

After the physiological needs are met, safety needs become important. They include establishing structure, order, and predictability in one’s life. These needs are related to feeling settled. For example, an unemployed person will constantly look for a stable job and a permanent place to live. He or she will be unable to focus on anything else until these needs are met.

Belongingness and love needs

At this stage a person desires companionship, a supportive family life and an intimate relationship. Maslow believed that if these needs were not met, a person would be consumed by loneliness and have no sense of belonging.

Esteem needs

The esteem needs include acceptance and recognition from other people as well as from oneself. This recognition boosts a person’s feelings of value and self-worth.

Self-actualization

Self-actualization is the highest level on Maslow’s hierarchy. Maslow believed that very few people actually ever attain this level. Self-actualization is characterized by a full acceptance and knowledge of one’s self and one’s own destiny.

People with realistic views often set realistic goals they can attain with their motivational levels and lifestyles. Maladjusted people tend to have unrealistic goals (too high or too low) that often end in failure or lack of fulfillment. Other problems with motivation may involve other people. One person may be motivated to control the actions of his or her spouse, but without a submissive partner, this motivation will not be realized. Motivation can change, however, and bring us closer to or farther from unhealthy behaviour!

Video: Maslow's Hierarchy of Human Needs

Deprivation or Trauma

If children do not have sufficient care and interaction from parents (or primary care givers) during the formative years (birth to approximately five years), they may experience adjustment difficulties into adulthood. Deprivation (the lack of or an insufficient amount of loving and frequent interaction) may also occur with children who have parents in the home. If a parent, for instance, is mentally ill, he or she may not be able to provide adequate care, love, and attention to his or her child. The more extreme forms of deprivation occur when children are abandoned or orphaned and placed in institutions or a series of inadequate foster homes.

A study by Provence and Lipton in the 1960s compared behaviour of infants living in institutions with that of infants living with families. The results of this study, recounted by Carson, Butcher, and Coleman, (1988) are as follows:

A study by Provence and Lipton in the 1960s compared behaviour of infants living in institutions with that of infants living with families. The results of this study, recounted by Carson, Butcher, and Coleman, (1988) are as follows:

|

“At one year of age, the institutionalized infants showed a general impairment in their relationships to people, rarely turning to adults for help, comfort or pleasure and showing no signs of strong attachment to any person. (They) also noted a marked retardation of speech and language development, emotional apathy, and impoverished and repetitive play activities. In contrast to the babies living in families, the institutionalized infants failed to show the personality differentiation and learning that can be thought of both as accomplishments of the first year of life and as the foundation upon which later learning is built.” |

Today, quality foster homes are more prevalent and the institutionalization of infants is rarely practiced. The importance of love and attention during the early years is very evident. Children who experience this type of deprivation may not recover, even if shown love and attention at a later time. The following is an account of “The Wild Boy of Aveyron.”

Itard’s “Wild Boy of Aveyron” Studies

In Aveyron, France, in 1800, hunters were stalking prey in a forest when they happened upon a “wild boy”. The boy was described as a savage without any of the refinements of a civilized person. The French government persuaded Jean Itard, a young doctor, to civilize and study the child. Itard did not favour the notion that a person’s behavior was predetermined, so he eagerly went about trying to “civilize” the young boy. The boy, who Itard named Victor, was covered in scratches and animal bites and could not speak. Itard worked very hard with Victor for five years with limited success. Victor was only able to learn to speak a few words, keep himself clean, and become affectionate to others. Itard, feeling his “experiment” with Victor was a failure, gave up trying to teach the boy and left Victor’s care to his housekeeper. Victor died at the age of 40.

Because Victor never learned to communicate fully, no one discovered how he came to live in the forest or how he was able to survive on his own. Modern psychologists have closely researched the case of Victor and have reached many differing opinions.

Because Victor never learned to communicate fully, no one discovered how he came to live in the forest or how he was able to survive on his own. Modern psychologists have closely researched the case of Victor and have reached many differing opinions.

Some believe that Victor was developmentally delayed or autistic, and that is why he never learned to speak or properly interact with other humans. Others argue that Victor could not have been developmentally delayed or he never would have survived for so long on his own. The same scientists also suggest that Victor may have missed important critical periods in his development and that is why he never became verbal or socially developed. Either way, the tragic case of Victor lends support to the notion that environment is very important in determining how we behave, and that genetics alone does not provide the entire blueprint for our behavior and personalities.

Deprivation for many children consists of having parents that provide distorted or inadequate care at home. Parents such as these neglect and often reject their children. Some children raised in such homes develop failure to thrive syndrome. This syndrome is a severe disorder of growth and development. The disturbing case of Genie illustrates severe parental neglect. Discovered in 1970 at the age of 13, Genie (not her real name) had lived in a state of extreme sensory and social deprivation. She was strapped to a potty-chair, not taught to speak, and was denied normal human interaction.

|

For more information on Genie, click on the link below: |

Video: The secret case of Genie Wiley, the wild child

Trauma

For the purpose of this course, the term trauma is used to mean any unpleasant experience that inflicts serious emotional damage on an individual. Not all negative experiences leave serious emotional scars, but the ones that do are often hard to eliminate. For example, a traumatic experience of being bitten by a vicious dog may be sufficient to establish a fear of all dogs for years to come, perhaps even for a lifetime. This fearful experience may even be generalized to other animals. The future effects of early traumatic experiences depend greatly on the support and reassurance given the child by parents or other significant individuals. A trauma does not have to ruin a person’s life!

Intergenerational trauma is a term used to describe how trauma-related stress can affect not only the survivor of the traumatic event, but also be passed down to second and subsequent generations. It facilitates the transmission of its negative consequences across generations. The root of the initial trauma may vary (eg. Holocaust survivor, victim of abuse etc.) We are going to further explore the intergenerational trauma experienced by the indigenous population as a result of the atrocities connected to the residential schools. Its effects are far reaching.

Read the following article on the impact of the residential schools on generations of children. Click here.

Read the following article on the impact of the residential schools on generations of children. Click here.

VIDEO: Watch the following video on the effects of intergenerational trauma on First Nations People.

Parenting

Some parents may neglect their children and, hence, deprive them of adequate contact and interaction. Other parents, however, interact with their children, but they do so in unhealthy ways. Parents can be overprotective and restrictive or overpermissive and indulgent. Parents can also be unrealistic and irrational. Restrictiveness, for example, may promote well-controlled and socialized behaviour. Restrictiveness may also nurture fear, dependency, and repressed hostility on the part of the child. Overindulged children raised in a permissive home may be selfish, inconsiderate, and demanding. When they mature, they may be shocked to learn that they will not get everything they want!

Some parents may neglect their children and, hence, deprive them of adequate contact and interaction. Other parents, however, interact with their children, but they do so in unhealthy ways. Parents can be overprotective and restrictive or overpermissive and indulgent. Parents can also be unrealistic and irrational. Restrictiveness, for example, may promote well-controlled and socialized behaviour. Restrictiveness may also nurture fear, dependency, and repressed hostility on the part of the child. Overindulged children raised in a permissive home may be selfish, inconsiderate, and demanding. When they mature, they may be shocked to learn that they will not get everything they want!

Children need to have realistic demands placed on them - neither too high nor too low. Parents who pressure their children to succeed in everything predispose their children for certain failure because no one person is an expert at all things. If a child raises a grade from 70% to 80%, the parent may criticize him or her for not getting 90%. Parents that do not care about achievement also do a disservice to their child. If the only thing a parent wants is for the child to stay out of trouble, then the child has no reason to strive to do well. The effort will not be recognized at home anyway! Parental recognition of realistic achievement is important to healthy emotional development.

Parenting is not easy. Relating to a child who needs guidance can be very stressful. Parents often punish instead of discipline. If they do discipline, it may be so inconsistent that the child cannot establish a set of values regarding appropriate behaviour. Open and honest communication between parent and children is also required for healthy development. For example, some parents are too busy to listen to the problems of their children; they fail to give them needed support in difficult situations. They may also be out of touch with the reality of the child’s generation.

With respect to faulty parenting, a last area is role modelling. Some children have such poor parental role models that they choose to be the exact opposite of their parents. This result could be a positive outcome. Many children, however, assume the negative aspects of the parental role model. If the parent is a bigot, the child may also grow up with prejudices. If the parent steals cable services, illegally copies DVD’s, etc., the child may grow up thinking that stealing is acceptable.

Family Structure

If a child is from an intact family (both parents or caregivers are present) but one of the adults is dissatisfied with the adult relationship, conflict may arise. This conflict may focus on sexual behaviour (e.g., infidelity), money, values, or work. The frustration may seriously affect everyone in the group relationship because arguing and conflict may be the norm instead of the exception.

If a child is from an intact family (both parents or caregivers are present) but one of the adults is dissatisfied with the adult relationship, conflict may arise. This conflict may focus on sexual behaviour (e.g., infidelity), money, values, or work. The frustration may seriously affect everyone in the group relationship because arguing and conflict may be the norm instead of the exception.

Parents can also be irrational, abnormal, or eccentric. One parent, for example, may be trying to deal with an ill partner at the expense of the child. If a mother has bipolar mood disorder, for instance, her partner may be focusing on maintaining his or her own mental health. The partner may then concentrate on ensuring the mother takes her medication and controls her illness. Attention to the child may be a distant third in the list of priorities of the non-ill parental figure. This is but one example of an unhealthy family structure.

Peers

As with familial relationships, peer relationships can be both healthy and unhealthy. Young children need to learn about give-and-take, empathy, kindness, and assertiveness with others. These are difficult concepts for adults to understand, so it is unreasonable to expect children to develop perfect peer relationship skills readily. Much trial and error will occur. Adult support is vital during this period of development. Some detrimental experiences that a child may face are school yard bullying and prejudice due to economic status, race, religious beliefs, gender, sexual orientation, physical characteristics, dress, or place of origin. Problems such as lowered self-confidence and self–esteem are often the result of negative childhood experiences.

As with familial relationships, peer relationships can be both healthy and unhealthy. Young children need to learn about give-and-take, empathy, kindness, and assertiveness with others. These are difficult concepts for adults to understand, so it is unreasonable to expect children to develop perfect peer relationship skills readily. Much trial and error will occur. Adult support is vital during this period of development. Some detrimental experiences that a child may face are school yard bullying and prejudice due to economic status, race, religious beliefs, gender, sexual orientation, physical characteristics, dress, or place of origin. Problems such as lowered self-confidence and self–esteem are often the result of negative childhood experiences.

Bullying is not confined to childhood. Many adults experience the negative effects of bullying in the workplace. Please review the following article (Chris Morris, 2004).

Bullying is not confined to childhood. Many adults experience the negative effects of bullying in the workplace. Please review the following article (Chris Morris, 2004).

Workplace bullying strikes chord in many, researcher finds

“Bullying targets usually good performers who react by quitting.” For fed-up nurses at one New Brunswick hospital, “code pink” is their unique way of coping with the scourge of the bully boss. The nurses could no longer stand the vile temper and bad language directed at them by one particularly belligerent physician, but hospital administrators were not sympathetic.

|

“They came up with a solution on their own to curb his behavior,” said Marilyn Noble, a Fredericton-based researcher in workplace bullying, “When he is on a rant, they call a code pink. Any nurse who can spare the time comes and stands in a circle as a silent observer and watches him. The impact is he looks up, realizes there are witnesses who might report him and he shuts down.” “If I talk to 100 people in social situations and I say I’m working on workplace bullying, there might be two people who look at me like I’ve got three heads, and there would be 98 who would grab me by the arm and say, “Have I got a story for you,’” she said. It’s a major safety issue, she said “Once in a while, we see people driven to such extremes they may lash out at the company, not only in the form of a lawsuit, but violently.” |

Workplace bullies—people who target workers for intimidation, belittlement and humiliation—are themselves are becoming the targets of individuals and groups promoting respectful and safe workplaces in Canada. Noble, one of two researchers studying workplace bullying at the Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research in Fredricton, says she has been besieged by people with stories to tell about bullies in their offices. Heather Gray of Edmonton, president and CEO of the consulting firm Threat Assessment and Management Associates Inc., said there’s much more at stake in controlling bullying than simply keeping workers happy and productive.

Workplace bullies—people who target workers for intimidation, belittlement and humiliation—are themselves are becoming the targets of individuals and groups promoting respectful and safe workplaces in Canada. Noble, one of two researchers studying workplace bullying at the Muriel McQueen Fergusson Centre for Family Violence Research in Fredricton, says she has been besieged by people with stories to tell about bullies in their offices. Heather Gray of Edmonton, president and CEO of the consulting firm Threat Assessment and Management Associates Inc., said there’s much more at stake in controlling bullying than simply keeping workers happy and productive.

Gray points to the case of OC Transpo in Ottawa, where four employees were fatally shot in April 1999 by Pierre Lebrun, who then took his own life. Lebrun had been teased and tormented for years by his co-workers at OC, but the company had never addressed the bullying problem.

|

“Self-esteem is damaged to the point where they’re not functioning well at work and in their personal relationships. It does an extraordinary amount of damage to the individual.” “There are mean-spirited people who have no power or control in other parts of their life so they exercise it in the workplace,” she said. “Some of these people have very poor interpersonal skills and there are others who simply get glee out of putting other people down and making them squirm.” |

Gray said she is particularly disturbed when firms boast that bullying tactics are their way of forcing people to quit. She says companies need to be aware of the damage caused by those tactics. Gray said bullies have a number of traits in common. They are usually in supervisory roles and their overriding objectives are power, domination and subjugation.

The targets of bullies also have traits in common. Gray said they’re generally good performers and are often targeted because of their competence, which may threaten the bully supervisor. Gray says targeted workers are not wired the same way as the bully and most quit their jobs.

Although federal legislation is pending that will help protect federal public servants from workplace bullies, most legislation in Canada offers little or no help. Noble says the ultimate solution is for companies to identify interveners at every level of their operations; unbiased people to whom workers can go with a complaint.

Video: Workplace Bullying

Lesson Review

The brain is a fascinating subject, don't you think?

|

To summarize: • Give examples of how psychosocial factors affect behaviour • Describe the Johari window and apply it to different scenarios • Explain Maslow's pyramid of needs • Discuss the effects of bullying |

Assignment

See assignments at the end of lesson booklet 3.