2.2 Variations in Family Life

The combination of husband, wife, and children that 80 percent of Canadians believes constitutes a family is not representative of the majority of Canadian families. According to 2011 census data, only 31.9 percent of all census families consisted of a married couple with children, down from 37.4 percent in 2001. Sixty-three percent of children under age 14 live in a household with two married parents. This is a decrease from almost 70 percent in 1981 (Statistics Canada 2012). This two-parent family structure is known as a nuclear family, referring to married parents and children as the nucleus, or core, of the group. Recent years have seen a rise in variations of the nuclear family with the parents not being married. The proportion of children aged 14 and under who live with two unmarried cohabiting parents increased from 12.8 percent in 2001 to 16.3 percent in 2011 (Statistics Canada 2012).

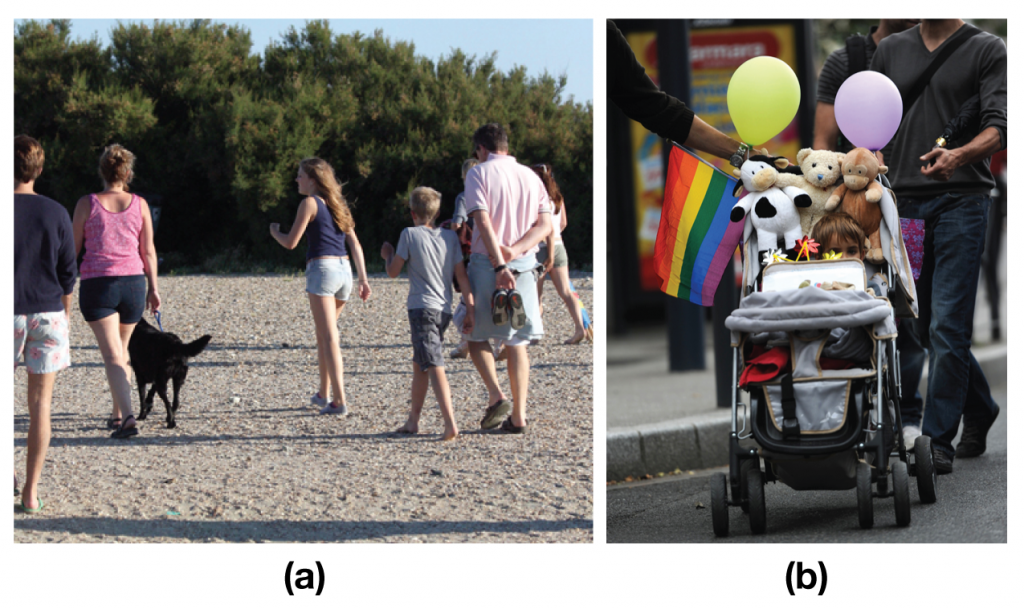

Figure 14.4. One in five Canadian children live in a single-parent household. (Photo courtesy of Ross Griff/flickr)

Single Parents

Single-parent households are also on the rise. In 2011, 19.3 percent of children aged 14 and under lived with a single parent only, up slightly from 18 percent in 2001. Of that 19.3 percent, 82 percent live with their mother (Statistics Canada 2012).

Stepparents are an additional family element in two-parent homes. A stepfamily is defined as “a couple family in which at least one child is the biological or adopted child of only one married spouse or common-law partner and whose birth or adoption preceded the current relationship” (Statistics Canada 2012). Among children living in two parent households, 10 percent live with a biological or adoptive parent and a stepparent (Statistics Canada 2012).

In some family structures a parent is not present at all. In 2010, 106,000 children (1.8 percent of all children) lived with a guardian who was neither their biological nor adoptive parent. Of these children, 28 percent lived with grandparents, 44 percent lived with other relatives, and 28 percent lived with non-relatives or foster parents. If we also include families in which both parents and grandparents are present (about 4.8 percent of all census families with children under the age of 14), this family structure is referred to as the extended family, and may include aunts, uncles, and cousins living in the same home. Foster children account for about 0.5 percent of all children in private households.

In the United States, the practice of grandparents acting as parents, whether alone or in combination with the child’s parent, is becoming more common (about 9 percent) among American families (De Toledo and Brown 1995). A grandparent functioning as the primary care provider often results from parental drug abuse, incarceration, or abandonment. Events like these can render the parent incapable of caring for his or her child. However, in Canada, census evidence indicates that the percentage of children in these “skip-generation” families remained more or less unchanged between 2001 and 2011 at 0.5 percent (Statistics Canada 2012).

Changes in the traditional family structure raise questions about how such societal shifts affect children. Research, mostly from American sources, has shown that children living in homes with both parents grow up with more financial and educational advantages than children who are raised in single-parent homes (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The Canadian data is not so clear. It is true that children growing up in single-parent families experience a lower economic standard of living than families with two parents. In 2008, female lone-parent households earned an average of $42,300 per year, male lone-parent households earned $60,400 per year, and two-parent families earned $100,200 per year (Williams 2010). However, in the lowest 20 percent of families with children aged four to five years old, single parent families made up 48.9 percent of households while intact or blended households made up 51.1 percent (based on 1998/99 data). Single parent families do not make up a larger percentage of low-income families (Human Resources Development Canada 2003). Moreover, both the income (Williams 2010) and the educational attainment (Human Resources Development Canada 2003) of single mothers in Canada has been increasing, which in turn is linked to higher levels of life satisfaction.

In research published from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, a long-term study initiated in 1994 that is following the development of a large cohort of children from birth to the age of 25, the evidence is ambiguous as to whether having single or dual parents has a significant effect on child development outcomes. For example, indicators of vocabulary ability of children aged four to five years old did not differ significantly between single- and dual-parent families. However, aggressive behaviour (reported by parents) in both girls and boys aged four to five years old was greater in single-parent families (Human Resources Development Canada 2003). In fact, significant markers of poor developmental attainment were more related to the sex of the child (more pronounced in boys), maternal depression, low maternal education, maternal immigrant status, and low family income (To et al. 2004). We will have to wait for more research to be published from the latest cycle of the National Longitudinal Survey to see whether there is more conclusive evidence concerning the relative advantages of dual- and single-parent family settings.

Nevertheless, what the data show is that the key factors in children’s quality of life are the educational levels and economic condition of the family, not whether children’s parents are married, common-law, or single. For example, young children in low-income families are more likely to have vocabulary problems, and young children in higher-income families have more opportunities to participate in recreational activities (Human Resources Development Canada 2003). This is a matter related more to public policy decisions concerning the level of financial support and care services (like public child care) provided to families than different family structures per se. In Sweden, where the government provides generous paid parental leave after the birth of a child, free health care, temporary paid parental leave for parents with sick children, high-quality subsidized daycare, and substantial direct child-benefit payments for each child, indicators of child well-being (literacy, levels of child poverty, rates of suicide, etc.) score very high regardless of the difference between single- and dual-parent family structures (Houseknecht and Sastry 1996).

Cohabitation

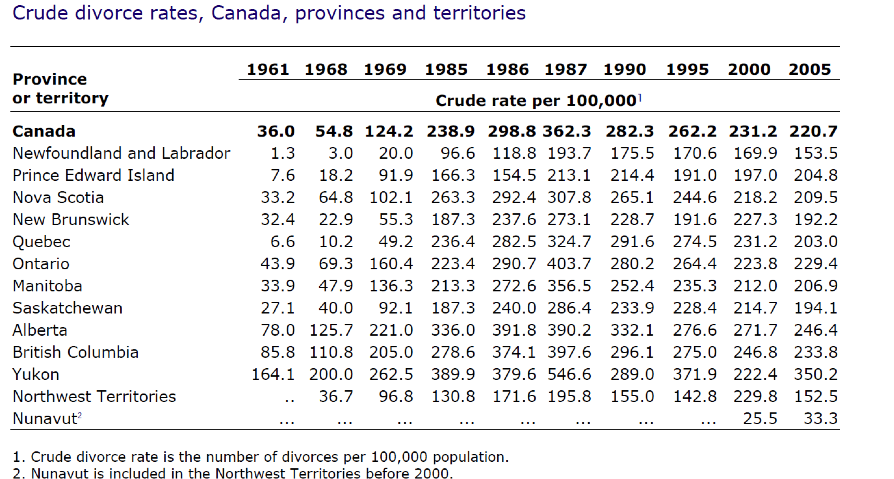

Living together before or in lieu of marriage is a growing option for many couples. Cohabitation, when a man and woman live together in a sexual relationship without being married, was practised by an estimated 1.6 million people (16.7 percent of all census families) in 2011, which shows an increase of 13.9 percent since 2006 (Statistics Canada 2012). This surge in cohabitation is likely due to the decrease in social stigma pertaining to the practice. In Quebec in particular, researchers have noted that it is common for married couples under the age of 50 to describe themselves in terms used more in cohabiting relationships than marriage: mon conjoint (partner) or mon chum (intimate friend) rather than mon mari (my husband) (Le Bourdais and Juby 2002). In fact, cohabitation or common-law marriage is much more prevalent in Quebec (31.5 percent of census families) and the northern territories (from 25.1 percent in Yukon to 32.7 percent in Nunavut) than in the rest of the country (13 percent in British Columbia, for example) (Statistics Canada 2012).

Cohabitating couples may choose to live together in an effort to spend more time together or to save money on living costs. Many couples view cohabitation as a “trial run” for marriage. Today, approximately 28 percent of men and women cohabitated before their first marriage. By comparison, 18 percent of men and 23 percent of women married without ever cohabitating (U.S. Census Bureau 2010). The vast majority of cohabitating relationships eventually result in marriage; only 15 percent of men and women cohabitate only and do not marry. About one-half of cohabitators transition into marriage within three years (U.S. Census Bureau 2010).

While couples may use this time to “work out the kinks” of a relationship before they wed, the most recent research has found that cohabitation has little effect on the success of a marriage. Those who do not cohabitate before marriage have slightly better rates of remaining married for more than 10 years (Jayson 2010). Cohabitation may contribute to the increase in the number of men and women who delay marriage. The average age of first marriage has been steadily increasing. In 2008, the average age of first marriage was 29.6 for women and 31 for men, compared to 23 for women and 25 for men through most of the 1960s and 1970s (Milan 2013).

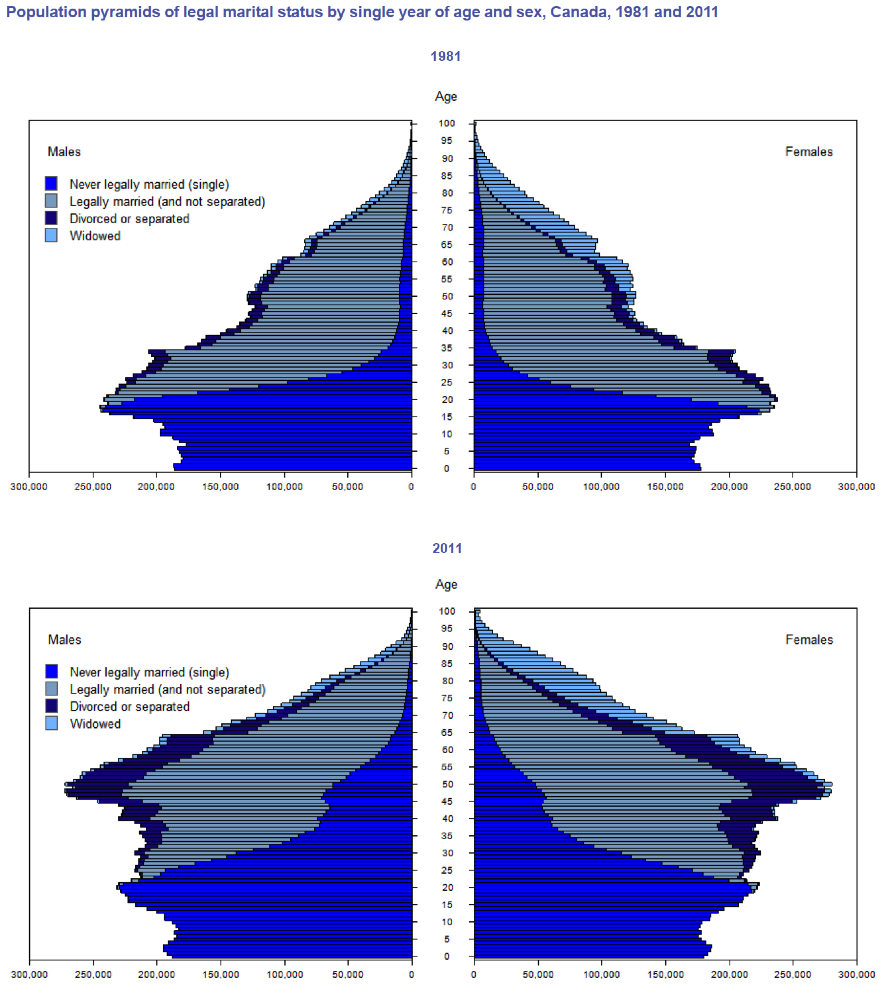

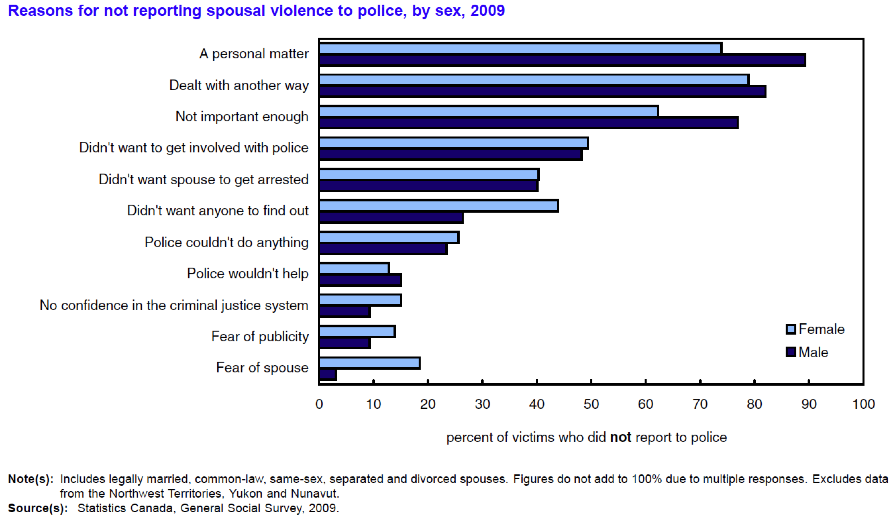

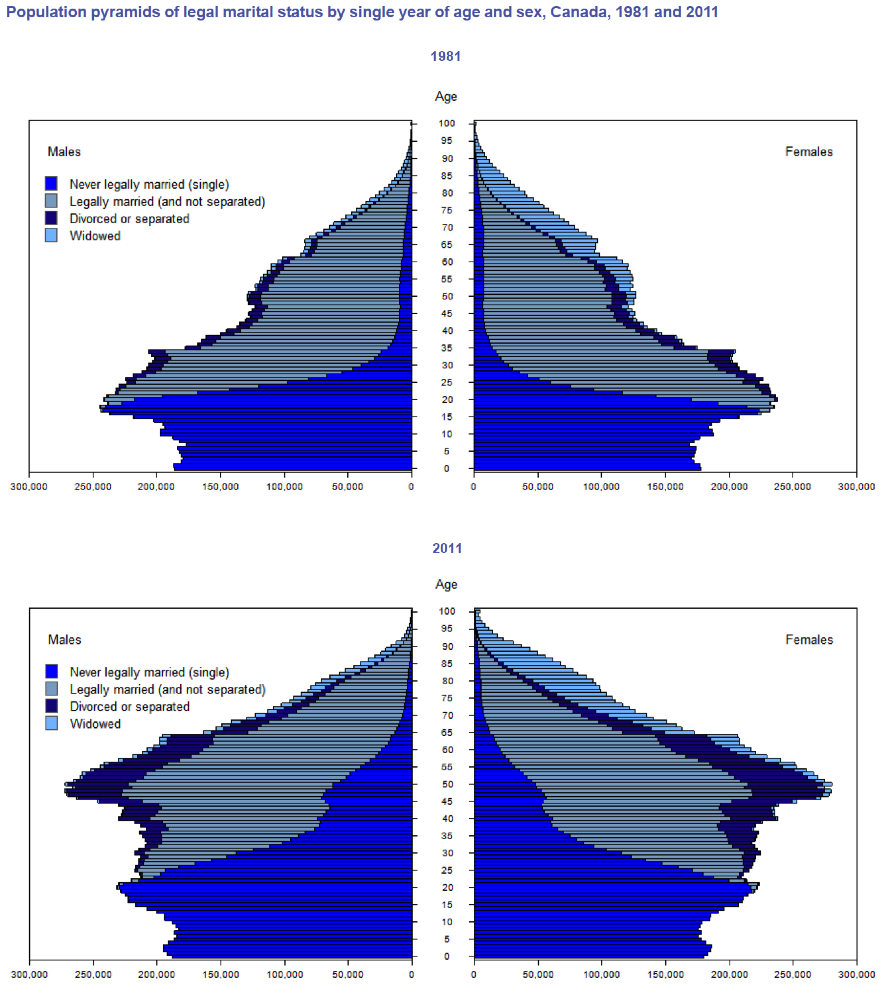

Figure 14.5 As shown by these population pyramids of marital status, more young people are choosing to delay or opt out of marriage (Milan, Anne. 2013; Population pyramids courtesy of Statistics Canada).

Same-Sex Couples

The number of same-sex couples has grown significantly in the past decade. The Civil Marriage Act (Bill C-38) legalized same sex marriage in Canada on July 20, 2005. Some provinces and territories had already adopted legal same-sex marriage, beginning with Ontario in June 2003. In 2011, Statistics Canada reported 64,575 same-sex couple households in Canada, up by 42 percent from 2006. Of these about three in ten were same-sex married couples compared to 16.5 percent in 2006 (Statistics Canada 2012). These increases are a result of more coupling, the change in the marriage laws, growing social acceptance of homosexuality, and a subsequent increase in willingness to report it.

In Canada, same-sex couples make up 0.8 percent of all couples. Unlike in the United States where the distribution of same-sex couples nationwide is very uneven, ranging from as low as 0.29 percent in Wyoming to 4.01 percent in the District of Columbia (U.S. Census Bureau 2011), the distribution of same-sex couples in Canada by province or territory is similar to that of opposite-sex couples. However, same-sex couples are more highly concentrated in big cities. In 2011, 45.6 percent of all same-sex sex couples lived in Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal, compared to 33.4 percent of opposite-sex couples (Statistics Canada 2012). In terms of demographics, Canadian same-sex couples tended to be younger than opposite-sex couples. Twenty-five percent of individuals in same-sex couples were under the age of 35 compared to 17.5 percent of individuals in opposite-sex couples. There were more male-male couples (54.5 percent) than female-female couples (Milan 2013). Additionally, 9.4 percent of same-sex couples were raising children, 80 percent of whom were female-female couples (Statistics Canada 2012).

While there is some concern from socially conservative groups, especially in the United States, regarding the well-being of children who grow up in same-sex households, research reports that same-sex parents are as effective as opposite-sex parents. In an analysis of 81 parenting studies, sociologists found no quantifiable data to support the notion that opposite-sex parenting is any better than same-sex parenting. Children of lesbian couples, however, were shown to have slightly lower rates of behavioural problems and higher rates of self-esteem (Biblarz and Stacey 2010).

Staying Single

Gay or straight, a new option for many Canadians is simply to stay single. In 2011, about one-fifth of all individuals over the age of 15 did not live in a couple or family (Statistics Canada 2012). Never-married individuals accounted for 73.1 percent of young adults in the 25 to 29 age bracket, up from 26 percent in 1981 (Milan 2013). More young men in this age bracket are single than young women—78.8 percent to 67.4 percent—reflecting the tendency for men to marry at an older age and to marry women younger than themselves (Milan 2013).

Although both single men and single women report social pressure to get married, women are subject to greater scrutiny. Single women are often portrayed as unhappy “spinsters” or “old maids” who cannot find a man to marry them. Single men, on the other hand, are typically portrayed as lifetime bachelors who cannot settle down or simply “have not found the right girl.” Single women report feeling insecure and displaced in their families when their single status is disparaged (Roberts 2007). However, single women older than 35 report feeling secure and happy with their unmarried status, as many women in this category have found success in their education and careers. In general, women feel more independent and more prepared to live a large portion of their adult lives without a spouse or domestic partner than they did in the 1960s (Roberts 2007).

The decision to marry or not to marry can be based a variety of factors including religion and cultural expectations. Asian individuals are the most likely to marry while black North Americans are the least likely to marry (Venugopal 2011). Additionally, individuals who place no value on religion are more likely to be unmarried than those who place a high value on religion. For black women, however, the importance of religion made no difference in marital status (Bakalar 2010). In general, being single is not a rejection of marriage; rather, it is a lifestyle that does not necessarily include marriage. By age 40, according to census figures, 20 percent of women and 14 of men will have never married (U.S. Census Bureau 2011).

Figure 14.6. More and more Canadians are choosing lifestyles that don’t include marriage. (Photo courtesy of Glenn Harper/flickr)

Theoretical Perspectives on Marriage and Family

Sociologists study families on both the macro and micro level to determine how families function. Sociologists may use a variety of theoretical perspectives to explain events that occur within and outside of the family. In this Introduction to Sociology, we have been focusing on three perspectives: structural functionalism, critical sociology, and symbolic interactionism.

Functionalism

When considering the role of family in society, functionalists uphold the notion that families are an important social institution and that they play a key role in stabilizing society. They also note that family members take on status roles in a marriage or family. The family—and its members—perform certain functions that facilitate the prosperity and development of society.

Sociologist George Murdock conducted a survey of 250 societies and determined that there are four universal residual functions of the family: sexual, reproductive, educational, and economic (Lee 1985). In each society, although the structure of the family varies, the family performs these four functions. According to Murdock, the family (which for him includes the state of marriage) regulates sexual relations between individuals. He does not deny the existence or impact of premarital or extramarital sex, but states that the family offers a socially legitimate sexual outlet for adults (Lee 1985). This outlet gives way to reproduction, which is a necessary part of ensuring the survival of society.

Once children are produced, the family plays a vital role in training them for adult life. As the primary agent of socialization and enculturation, the family teaches young children the ways of thinking and behaving that follow social and cultural norms, values, beliefs, and attitudes. Parents teach their children manners and civility. A well-mannered child reflects a well-mannered parent.

Parents also teach children gender roles. Gender roles are an important part of the economic function of a family. In each family, there is a division of labour that consists of instrumental and expressive roles. Men tend to assume the instrumental roles in the family, which typically involve work outside of the family that provides financial support and establishes family status. Women tend to assume the expressive roles, which typically involve work inside of the family, which provides emotional support and physical care for children (Crano and Aronoff 1978). According to functionalists, the differentiation of the roles on the basis of sex ensures that families are well balanced and coordinated. Each family member is seen as performing a specific role and function to maintain the functioning of the family as a whole.

When family members move outside of these roles, the family is thrown out of balance and must recalibrate in order to function properly. For example, if the father assumes an expressive role such as providing daytime care for the children, the mother must take on an instrumental role such as gaining paid employment outside of the home in order for the family to maintain balance and function.

Critical Sociology

Critical sociologists are quick to point out that North American families have been defined as private entities, the consequence of which historically has been to see family matters as issues concerning only those within the family. Serious issues including domestic violence and child abuse, inequality between the sexes, the right to dispose of family property equally, and so on, have been historically treated as being outside of state, legal, or police jurisdiction. The feminist slogan of the 1960s and 1970s—“the personal is the political”—indicates how feminists began to draw attention to the broad social or public implications of matters long considered private or inconsequential. As women’s roles had long been relegated to the private sphere, issues of power that affected their lives most directly were largely invisible. Speaking about the lives of middle-class women in mid-century North America, Betty Friedan described this problem as “the problem with no name”:

The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the 20th century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—“Is this all?” (1963, p. 15).

One focus of critical sociology therefore is to highlight the political-economic context of the inequalities of power in family life. The family is often not a haven but rather an arena where the effects of societal power struggles are felt. This exercise of power often entails the differentiation and performance of family status roles. Why are women expected to perform the “expressive” roles in the family while the men perform “instrumental” roles, and what are the implications of this division of labour? Critical sociologists therefore study conflicts as simple as the enforcement of rules from parent to child, or more serious issues such as domestic violence (spousal and child), sexual assault, marital rape, and incest, as products of power structures in broader society. Blood and Wolfe’s classic (1960) study of marital power found that the person with the most access to value resources held the most power. As money is one of the most valuable resources, men who worked in paid labour outside of the home held more power than women who worked inside the home. Disputes over the division of household labour tend also to be a common source of marital discord. Household labour offers no wages and, therefore, no power. Studies indicate that when men do more housework, women experience more satisfaction in their marriages, reducing the incidence of conflict (Coltrane 2000).

The political and economic context is also key to understanding changes in the structure of the family over the 20th and 21st centuries. The debate between functionalist and critical sociologists on the rise of non-nuclear family forms is a case in point. Since the 1950s, the functionalist approach to the family has emphasized the importance of the nuclear family—a married man and woman in a socially approved sexual relationship with at least one child—as the basic unit of an orderly and functional society. Although only 39 percent of families conformed to this model in 2006, in functionalist approaches, it often operates as a model of the normal family, with the implication that non-normal family forms lead to a variety of society-wide dysfunctions. On the other hand, critical perspectives emphasize that the diversity of family forms does not indicate the “decline of the family” (i.e., of the ideal of the nuclear family) so much as the diverse response of the family form to the tensions of gender inequality and historical changes in the economy and society. The nuclear family should be thought of less as a normative model for how families should be and more as an historical anomaly that reflected the specific social and economic conditions of the two decades following the World War II.

Symbolic Interactionism

Interactionists view the world in terms of symbols and the meanings assigned to them (LaRossa and Reitzes 1993). The family itself is a symbol. To some, it is a father, mother, and children; to others, it is any union that involves respect and compassion. Interactionists stress that family is not an objective, concrete reality. Like other social phenomena, it is a social construct that is subject to the ebb and flow of social norms and ever-changing meanings.

Consider the meaning of other elements of family: “parent” was a symbol of a biological and emotional connection to a child. With more parent-child relationships developing through adoption, remarriage, or change in guardianship, the word “parent” today is less likely to be associated with a biological connection than with whoever is socially recognized as having the responsibility for a child’s upbringing. Similarly, the terms “mother” and “father” are no longer rigidly associated with the meanings of caregiver and breadwinner. These meanings are more free-flowing through changing family roles.

Interactionists also recognize how the family status roles of each member are socially constructed, playing an important part in how people perceive and interpret social behaviour. Interactionists view the family as a group of role players or “actors” that come together to act out their parts in an effort to construct a family. These roles are up for interpretation. In the late 19th and early 20th century, a “good father,” for example, was one who worked hard to provided financial security for his children. Today, a “good father” is one who takes the time outside of work to promote his children’s emotional well-being, social skills, and intellectual growth—in some ways, a much more daunting task.

Symbolic interactionism therefore draws our attention to how the norms that define what a “normal” family is and how it should operate come into existence. The rules and expectations that coordinate the behaviour of family members are products of social processes and joint agreement, even if the agreements are tacit or implicit. In this perspective, norms and social conventions are not regarded as permanently fixed by functional requirements or unequal power relationships. Rather, new norms and social conventions continually emerge from ongoing social interactions to make family structures intelligible in new situations and to enable them to operate and sustain themselves.