World Views Information

| Site: | MoodleHUB.ca 🍁 |

| Course: | Aboriginal Studies 10 RVS |

| Book: | World Views Information |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Saturday, 27 December 2025, 2:41 AM |

Description

World Views

Introduction to Worldviews

The First Nations World View

People from different cultures have different ways of seeing, explaining and living within the world. They have different ideas about what things are most important, which behaviors are desirable or unacceptable, and how all parts of the world relate to each other. Together, these opinions and beliefs form a worldview, the perspective from which people perceive, understand and respond to the world around them.

People from the same culture tend to have similar worldviews. A culture’s worldview evolves from its history, which is the collective experience of the people within the culture over all the years of its existence. It also includes their beliefs about origin and spiritualism.

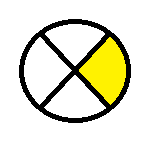

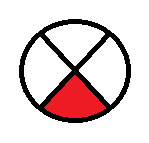

The traditional world view of First Nations and Inuit peoples in Canada differ from the worldviews of people with a non-Aboriginal ancestry. You might compare a First Nations or Inuit worldview to a Euro-Canadian worldview by drawing a circle and a line. The circular First Nations worldview focuses on connections between all things, including the visible physical world and the invisible spiritual world. It sees time as always a cycle of renewal that links past and present and future. In contrast, a linear Euro-Canadian worldview lays out separations between elements of existence (spiritual and material, life and death, animal and human, living and non-living) and sees time as a progression from point to point.(Aboriginal Perspectives 2004, 66-67)

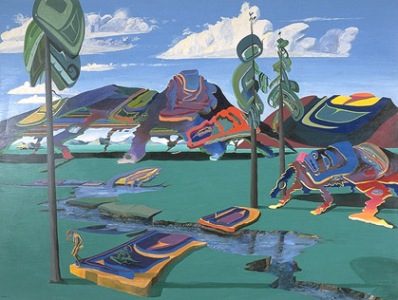

Lawerence B. Paul

Perhaps one of the biggest differences between the two world views is the attitude toward the environment. A vital lesson still to be learned in the developed world is that the Earth, its atmosphere and its waters belong to all people. According to Ken Goodwill, Sioux spiritual leader and lecturer at the First Nations University of Canada, Aboriginal peoples have a unique relationship with their Earth Mother, and they relate all human activities to the Earth Mother. The cultures of Aboriginal peoples are holistic; that is, they are totally integrated in their connection to the Earth Mother. Many First Nations peoples believe that they come from the womb of the Earth itself. For example, when the Sioux refer to “all their relations,” they

refer to all living things, be they animal or plant. Further, all things, animate and inanimate, possess spiritual significance.

There is no single worldview common to all First Nations, Métis and Inuit individuals. In learning about traditional First Nations and Inuit worldviews, however, it is possible to identify several similarities between many First Nations peoples’ cultures. Five strong threads that are common in Aboriginal world view are:

- a holistic perspective,

- the interconnectedness of all living things,

- connections to the land and community,

- the dynamic nature of the world

- the strength of “power with” rather than “power over.”

The image for this concept is a circle, in which all living things are equal. “Power with” is a dialogue during which everyone stands face to face (Alberta Education 2005, 13).

First Peoples Spirituality

First Peoples Spirituality

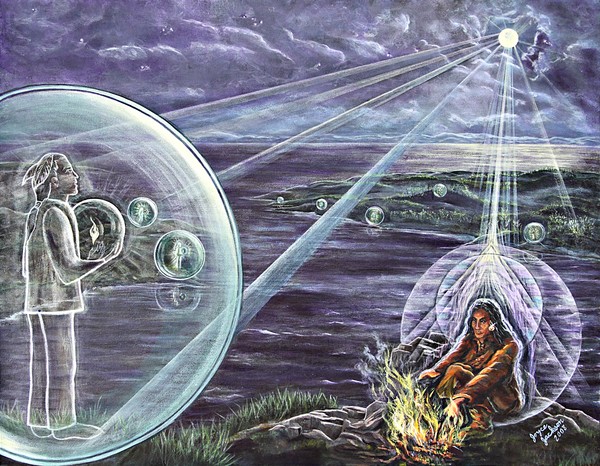

First Nations people and Inuit who follow traditional ways believe in a higher power called the Great Spirit or the Creator. Spirituality is a part of being alive and a part of everyday life (Kainai Board of Education et al 2005, 68). This world view presents human beings as inhabiting a universe made by the Creator and striving to live in a respectful relationship with nature, one another and oneself (Alberta Education 2005, 156). Everything in the universe possesses a kind of power or energy, similar to soul; this power is capable of transferring to birds, animal and humans. For example, animals that become prey are part of a natural cycle whereby they offer themselves to become sustenance for the people. In return, the people honour the animals’ spirits by offering prayers.

First Nations people and Inuit who follow traditional ways believe in a higher power called the Great Spirit or the Creator. Spirituality is a part of being alive and a part of everyday life (Kainai Board of Education et al 2005, 68). This world view presents human beings as inhabiting a universe made by the Creator and striving to live in a respectful relationship with nature, one another and oneself (Alberta Education 2005, 156). Everything in the universe possesses a kind of power or energy, similar to soul; this power is capable of transferring to birds, animal and humans. For example, animals that become prey are part of a natural cycle whereby they offer themselves to become sustenance for the people. In return, the people honour the animals’ spirits by offering prayers.

Like many other groups, First Nations people and Inuit place a great deal of faith in the power of prayer. Prayers thanking the Creator for all the blessings are offered during ceremonies such as sweats, at feasts and meetings, and at the beginning and end of the day. Ceremonies are the primary vehicle for spiritual expression. A ceremonial leader or elder ensures the authenticity and integrity of spiritual observances. Nothing is written down, as the very act of writing would negate the significance of the ceremony. Teachings are therefore passed on from elder to elder in a strictlyoral tradition.

Most First Nations and Inuit groups have varied beliefs and spiritual practices. What is most important is that some of the knowledge relating to spiritual beliefs and practices is privileged by those who are members of the community. It is an honour to be invited to share in sacred ceremonies.

Mi'kmaq Creation Stories

Listen to Elder Stephen Augustine as he shares the Mi"kmaq story of creation.

Listen to Elder Stephen Augustine as he shares the Mi"kmaq story of creation.

Introduction

The Giver of Life

Grandfather Sun

Mother Earth

Glooscap

Grandmother

Nephew

Mother

You may also read along using the Mi'kmaq Creation Story as well.

Mohawk Creation Stories

Listen to Elder Tom Porter as he shares the creation stories of the Mohawk (Haudenosaunee).

Listen to Elder Tom Porter as he shares the creation stories of the Mohawk (Haudenosaunee).

Creation of the World

Creation of the Twins

Creation of the Humans

You may also read along with the Mohawk Creation Story as well.

Metis Spirituality

Métis Spirituality

To understand Métis spirituality, one must understand Métis history. However, identifying a single starting point of the Métis people is difficult.

|

“Scholars searching for the roots of the -historian Grant MacEwan (1981, 3) |

Historically, the Métis can define their nationhood by important events, such as the battle of Seven Oaks in 1816, or the Riel Resistances of 1869/70 and 1885. If we look at these historical events as the start of Métis culture and spiritualism, we can see that the Métis show an affinity for European concepts of religion. Cuthbert Grant, Métis leader during the battle of Seven Oaks, was formally educated in Scotland. Riel was chosen by the Catholic

Church to go into the seminary. Churches at Batoche and Red River, where priests presided during the buffalo hunt, and much historical documentation show that seminal Métis figures were rooted in Christianity.

This is not to say that the First Nations mothers of the Métis Nation had little influence. Being caught between the European and First Nations traditions has been a condition of Métis consciousness from the very beginning, and many proud Métis have practised traditional First Nations spiritualism.

Today Métis people most often practise one of three categories of spirituality: First Nations spirituality, Christianity or a blend of the two.

The common misconception is that the Métis practiced only the religion of their fathers (Catholicism or Protestant). The truth is that like the Métis Nation itself, the spiritual mixture is as complex as the people who make up the nation.

As we see this ability to learn from all of the nations they came in contact with, added to the future spirituality of the Métis.

Today Métis practice all forms of religion, from mainline Christianity to New Age concepts and everything in between. From their Catholicism they have the Patron Saint of Métis people, St. Joseph of Nazareth. From their Aboriginal relatives they incorporate the sweat lodge, medicine wheel, sacred pipe and Long House ceremonies, and many other Aboriginal spiritual beliefs.

Many Métis people, as with other Aboriginal communities, have lost their spiritual connections to the past because of marginalization or poverty and decimation of their communities and their way of life. The healing has begun and the renewal of their spirituality is an exciting journey that many Métis people are taking.

Many Métis people, as with other Aboriginal communities, have lost their spiritual connections to the past because of marginalization or poverty and decimation of their communities and their way of life. The healing has begun and the renewal of their spirituality is an exciting journey that many Métis people are taking.

Inuit Spirituality

For at least 5,000 years, the people and culture known throughout the world as Inuit have occupied a vast territory, one-third of Canada’sland mass, in the Arctic. This region continues to be shaped by natural forces into seemingly endless

tundra, magnificent mountains and countless islands.

Traditionally, the land and the sea have provided everything the Inuit need. Their history is about people and their relationship to the environment and to each other; about dealing with change as well as the causes and consequences of change forced on them by colonialism; and about how they have re-established control over their cultural, economic and political destiny through land claims and self-government. Above all, it is about how the people are able to live in balance with the natural world.

The ancestors depended on their ability to maintain good relations with the spirits of both the animate and inanimate worlds. They recognized that they had to be careful, by respecting the animals and the spirit world.

Shamanism was common to most hunting cultures around the world. It embodies the people’s attachment to the land and environment. In traditional Inuit society, the Shaman was seen as a doctoradvisor- healer. The Shaman was not seen as camp leader; that role was given to the oldest person with experience hunting and trapping.

Inuit camps could have more than one Shaman, and the Shaman could be either a woman or a man. Shamans were born, not made. They had to have the ability to vision, to see spirits.As with Christianity and other religions, Shamanism was never meant as an instant remedy for problems. Shamanism was respected and used only as a last resort.

|

In my family, according to my mother, her family relations were known to practise Shamanism. One in particular named Tagonagag, who died an old elder, was the last person my mother had known to be a Shaman. He was considered to be a strong person, tall and muscular, and had the ability to work and play with even the biggest animals, including a polar bear. It was even said that he had the polar bear as a pet and protector.

|

Today in Nunavut, Shamanism is still practised secretly, not openly practised as in other places like Russia. Interestingly, it is discussed by curious young Inuit who have heard that Shamanism is a good way to heal. They see it as a positive tool.

Shamanism is the original religion of the Inuit. It was a way of life for many years before Roman Catholic and Anglican missionaries arrived on the heels of European traders to forcibly replace Shamanism with Christianity. Some Europeans even considered Shamanism an “act of the devil.”

The Inuit believe in the spirits who help them whether on the land or in seeking and finding animals. According to Nattilikmiut, they believe in the existence of Naarjuk. This supreme being, equivalent to the Christian God, made the earth and water. It is believed that he exists somewhere in the universe. He is the boss of sila, the sky, looking after all our relations who have passed away.

Nuliajuk, the spirit of the sea, is the boss of all sea animals. Europeans refer to her as the “Sea Goddess.”

Many Inuit traditional names are spiritual.

The Angakoq - The Shaman

During difficult times, people turned for assistance to the angakoqs to help cure the sick, control the weather, or improve the hunting. Angakoqs were both men and women. One could not, however, just choose to be a shaman; this was a role to which you were born.

Kaj Birket-Smith writes that “an Eskimo almost never becomes a shaman of his own free will; it is sila [or nature and the spiritual universe] or the spirits themselves who, through dreams or some other manner, appoint the chosen one” (Mitchell 1996:36).

Kaj Birket-Smith writes that “an Eskimo almost never becomes a shaman of his own free will; it is sila [or nature and the spiritual universe] or the spirits themselves who, through dreams or some other manner, appoint the chosen one” (Mitchell 1996:36).

Under the guidance of an angakoq trainer, the initiate learned how to communicate with the spirit world.

Not Always for Free

Angakoqs provided help both to individuals and to the group. If someone were sick, the angakoqs would make them well; if a wife had trouble conceiving, they would appeal to the spirits to bring her a child. Angakoqs would also look out for the group as a whole, performing rituals to ensure good weather or a successful hunt. The main difference between the two services related to payment. For services rendered to individuals, the angakoq might expect to receive food or a knife. If the work was done for the benefit of the community to ensure a good hunt, for instance, it was performed for free. It seems reasonable to speculate that a good hunt was as much in the interest of the shaman as it was in the interests of the group (p. 37).

Visionary Powers

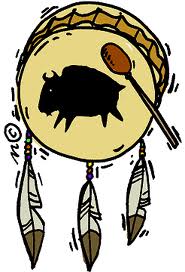

Angakoqs also possessed visionary powers. Pauta Saila of Cape Dorset once spoke of a prediction song performed by Atsiluaq, a shaman who lived several generations before the arrival of the qallunaat (white people). In 1997 he said, “At a huge gathering in a qaggiq [a large ceremonial igloo], Atsiluaq took the drum and began to sway back and forth, beating the circular instrument with a thick, rounded baton ... he began his new song:

Atsiluaq, this man

He would be called a great shaman

"Hooo ... Hoooo ... Hoooo ... Hoooo ...

There, over there

The high mountain

In the front, over there you will see

A lovely cloth

A lovely red shade

Atsiluaq, this man

He would be called a great shaman

Hoooo ... Hooo ... Hoooo ... Hoooo..."

Saila continues: “Atsiluaq was one of the last well-known shamans who saw into the future. He saw this lovely red cloth fluttering in the wind. He was telling his people that the qallunaat (white people) were coming and they will fly a flag that contains red shades. The Hudson’s Bay Company flag and the Canadian flag both contain red colours. Atsiluaq was right” (Hanson 1998:68-9).

Spirituality Assignment

After reading about the spirituality of First Nations, Inuit and Métis please complete the assignment below.

After reading about the spirituality of First Nations, Inuit and Métis please complete the assignment below.

The Sacred Circle

The Sacred Circle

The circle is a universal symbol of connection, unity, harmony, wholeness and eternity. In a circle all parts are equal (Kainai Board of Education et al 2005, 87). The circle is an important symbol, because the First Nations’ belief system holds that everything is circular. Life is circular—a person is born, grows into childhood, matures and becomes old, at which point thoughts and actions become childlike again. The seasons are cyclical. Earth moves in a circle. Everything moves in a circle, from the rising sun to the setting sun, from the east and back to the east. The day is divided into four segments of time: sunrise, noon, sunset and night.

The circle also symbolizes inclusion and equality. In traditional First Nations meetings or gatherings, everyone sits in a circle in accordance with the belief that all people are equal. This symbol is drawn on teepees, woven into clothing and made into ornamental parts of one’s national dress. The circle is also the basis of many beautiful works of jewellery and art, which are precious possessions.

The circle teaches that four elements—mental, spiritual, emotional, and physical—are distinctive and powerful yet interconnected components of

a balanced human life. Each of the four elements represents a particular way of perceiving things, but none is considered superior to or more significant than the others, and all are to be equally respected. The emphasis is always placed on the

need to seek and explore the four great ways in order to gain a thorough understanding of one’s own nature in relation to the surrounding world. Today, these four elements are often expressed in the medicine wheel, which has been adopted by many First Nations people regardless of whether it is part of their traditional culture. Just as the acorn carries within it the potential to become a mighty oak tree, the four aspects of our nature (physical, mental, emotional and spiritual) are like seeds that have the potential to grow into powerful gifts (

Alberta Education 2005, 87).

Other aspects of life can be symbolized using the circle or medicine wheel. For example, the four symbolic races (red, white, yellow and black) express the idea that we are all part of the same human family. All are brothers and sisters living on the same Mother Earth. The four stages oflife—infancy, youth, maturity and old age—relate to a person’s life cycle. Each part of the life cycle is characterized by celebrations and rituals. There are many variations in the ways this basic concept is expressed: the four directions, the four winds, the four sacred plants and other relationships that can be expressed in sets of four.

Other aspects of life can be symbolized using the circle or medicine wheel. For example, the four symbolic races (red, white, yellow and black) express the idea that we are all part of the same human family. All are brothers and sisters living on the same Mother Earth. The four stages oflife—infancy, youth, maturity and old age—relate to a person’s life cycle. Each part of the life cycle is characterized by celebrations and rituals. There are many variations in the ways this basic concept is expressed: the four directions, the four winds, the four sacred plants and other relationships that can be expressed in sets of four.

Among the First Nations groups in Canada, the four sacred plants—tobacco, sage, sweetgrass and cedar—are used in sacred ceremonies to help participants enter them with a good heart. These herbs are usually burned, and people carry out

ritual actions using the smoke to cleanse their bodies and spirits. In the sweetgrass ceremony, also called a smudge, sweetgrass is used to symbolically

cleanse the body and important objects. During pipe ceremonies where tobacco is offered, the smoke represents one’s visible thought; tobacco travels ahead of the words so that honesty will be received in a kind and respectful way (Kainai Board of Education et al 2005, 93).

Tobacco can be used as a gift, in ceremonies, in prayer and as a medicine (commercial tobacco should not be used as medicine because it contains harmful chemicals). Tobacco was never meant to be used as it is today, smoked indiscriminately to the detriment of one’s health. When people want advice from an elder or prayers said on their behalf, they should first offer the elder tobacco.

The Blackfoot

|

"Many elders believe that there is an oral circle, or system, that exists across all the first nations of North America, and that we are all a part of. Our Piikani Blackfoot systems are only a part of that greater circle. We are honoured to share with you our Piikani perspective, as part of that great circle that unites us all." Dr. Reg Crowshow - FourDirections Teaching.com |

Listen as Dr. Reg Crowshow describes the Tipi Circle model for the Blackfoot people.

You may also read along with the Tipi Circle Model as well.

Ojibwe

Listen to Elder Lillian Pitawanakwat as she explains the sacred circle as it is for the Ojibwe people.

Listen to Elder Lillian Pitawanakwat as she explains the sacred circle as it is for the Ojibwe people.

Introduction

Centre

The East

The South

The West

The North

Cree

Listen To Cree Elder Mary Lee describe their sacred circle of East, South, West and North.

Listen To Cree Elder Mary Lee describe their sacred circle of East, South, West and North.

East

South  SOUTH - mp3 format

SOUTH - mp3 format

West

North

You may also read along with the Cree Sacred Circle as well.

The Sacred Circle Assignment

After reading about the sacred circle, please complete the following Sacred Circle Assignment

After reading about the sacred circle, please complete the following Sacred Circle Assignment

Elders

Elders

Elders are men and women regarded as the keepers and teachers of an Aboriginal nation’s oral traditions and knowledge. Different elders hold different gifts. They can make significant contributions by bringing traditional ceremonies and teachings into the school and classroom; providing advice to parents, students, teachers and school administrators; providing information about Aboriginal

communities; and acting as a bridge between the school and the community.

Elders are considered vital to the survival of Aboriginal cultures, and the transmission of cultural knowledge is an essential part of the preservation and promotion of cultural traditions and their protocols. Elders are always to be treated with great respect and honour. The roles of elders vary greatly from community to community, as do the protocols and traditions they teach.

Elders often perform such services as:

• giving prayers before meetings

• describing or performing traditional ceremonies

• sharing traditional knowledge

• giving spiritual advice to individuals

. demonstrating traditional crafts and practices

• teaching the community’s protocols.

The Blackfoot

|

"What is life? It is the flash of a firefly in the night. It is the breath of a buffalo in the wintertime. It is the little shadow which runs across the grass and loses itself in the sunset." Crowfoot, Blackfoot Warrior and Orator, 1821-1890 |

Listen to Dr. Reg Crowshoe talking about how the Blackfoot view the world from our Piikani belief systems - those forms of knowledge that have been in place for thousands of years.

You may also read along with the Blackfoot Elders Page as well.

Medicine People

Medicine People

Healing practices of First Nations people encompass the healing beliefs of a therapeutic approach that combines spirituality, ceremony, herbalism, nutrition and the family, in treating a wide range of physical and emotional ailments. First Nations medicine uses a holistic approach that emphasizes the treatment of body, mind and spirit (University of Alberta 2004, 1–131). To First Nations, the term medicine is not restricted to herbal or chemical remedies for illness, although it can, of course, include these things. Medicine traditionally includes spiritual energy and enlightenment. The medicine people of traditional societies were powerful people who communicated with the spirit world. They used their knowledge and powers to benefit the community and strengthen spiritual balance. In traditional First Nations societies, medicine people had the job of restoring a person’s balance—physically, emotionally and spiritually (Kainai Board of Education et al 2005, 89). Modern medicine people are trained over the years as healers. The healer is a link to the spiritual world and is held in very high regard. The healer may prescribe herbal remedies to relieve symptoms of an ailment. Purification rituals may be used to cleanse the body (University of Alberta 2004, 1–131).

Healing practices of First Nations people encompass the healing beliefs of a therapeutic approach that combines spirituality, ceremony, herbalism, nutrition and the family, in treating a wide range of physical and emotional ailments. First Nations medicine uses a holistic approach that emphasizes the treatment of body, mind and spirit (University of Alberta 2004, 1–131). To First Nations, the term medicine is not restricted to herbal or chemical remedies for illness, although it can, of course, include these things. Medicine traditionally includes spiritual energy and enlightenment. The medicine people of traditional societies were powerful people who communicated with the spirit world. They used their knowledge and powers to benefit the community and strengthen spiritual balance. In traditional First Nations societies, medicine people had the job of restoring a person’s balance—physically, emotionally and spiritually (Kainai Board of Education et al 2005, 89). Modern medicine people are trained over the years as healers. The healer is a link to the spiritual world and is held in very high regard. The healer may prescribe herbal remedies to relieve symptoms of an ailment. Purification rituals may be used to cleanse the body (University of Alberta 2004, 1–131).

Elders Assignment

After reading about native elders, please complete the following Elders Assignment.

After reading about native elders, please complete the following Elders Assignment.

Ceremonies

First Nations and Inuit peoples from across the continent share a tradition of regularily giving thanks, through everyday acts, through rituals and through ceremonies. A ceremony is a formal act or series of acts performed as prescribed by custom, law or other authority. Ceremonies can be simple or elaborate solemn occasions or forms of celebration. First Nation celebrations are often a means of thanking everyone in the community for their contributions.

Ceremonial gatherings remain at the heart of First Nations spiritual and cultural practices today. The significance of these ceremonial practices remains true to the sacred teachings that go back to the beginning of time.

Ceremonial gatherings remain at the heart of First Nations spiritual and cultural practices today. The significance of these ceremonial practices remains true to the sacred teachings that go back to the beginning of time.

Gift-giving is an important part of many First Nations ceremonial gatherings. People traditionally offer their best and most valuable goods to sacrifice or distribute t guests or members of their community. Such gifts are a recognition that resources are meant to be shared. They are also thought to encourage the spiritual world to be as generous.

Many First Nations people believe that in order for the balance of all living things to continue, proper protocols must be followed. Protocols ensure that ceremonies will be remembered from generation to generation and that values of the culture will be upheld through time.

(Aboriginal Perspectives 2004, 91)

Examples of Ceremonies

The Tea Dance

For the Dene Tha' people of Alberta, the dawots'ethe, which means dance, is the most significant ceremonial gathering. It is traditionally held to commemorate a death, mark a season change, or celebrate the end of a successful hunt.

Please watch a short clip from a Tea Dance

The Round Dance

The Round dance held by the Woodland Cree is called the maskisimowin. It is similar in function and form to the Tea Dance

Please watch a short clip of the Round Dance

The Smudging Ceremony

The following is a description of the Smudging Ceremony by Adrienne Borden amd Steve Coyote:

Our Native elders have taught us that before a person can be healed or heal another, one must be cleansed of any bad feelings, negative thoughts, bad spirits or negative energy - cleansed both physically and spiritually. This helps the healing to come through in a clear way, without being distorted or sidetracked by negative "stuff" in either the healer or the client. The elders say that all ceremonies, tribal or private, must be entered into with a good heart so that we can pray, sing, and walk in a sacred manner, and be helped by the spirits to enter the sacred realm.

Native people throughout the world use herbs to accomplish this. One common ceremony is to burn certain herbs, take the smoke in one's hands and rub or brush it over the body. Today this is commonly called "smudging." In Western North America the three plants most frequently used in smudging are sage, cedar, and sweetgrass.

Sage

There are many varieties of sage, and most have been used in smudging. The botanical name for "true" sage is Salvia (e.g. Salvia officinalis, Garden Sage, or Salvia apiana, White Sage). It is interesting to note that Salvia comes from the Latin root salvare, which means "to heal." There are also varieties of sage which are of a species separate from Salvin Artemusia. Included here are sagebrush (e.g. Artemisia californica) and mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris). We have seen both Salvia and Artemisia sub-species used in smudging.

Sage is burned in smudging ceremonies to drive out bad spirits, feelings, or influences, and also to keep bad spirits from entering the area where a ceremony takes place. In Plains nations, the floor of the sweat lodge is frequently covered with sage, and participants rub the leaves on their bodies while in the sweat. Sage is also commonly spread on the ground in a lodge or on an altar where the pipe touches the earth. Some nations wrap their pipes in sage when they are placed in pipe-bundles, as sage purifies objects wrapped in it. Sage wreaths are also placed around the head and wrists of Sundancers.

Cedar

There is some potential confusion here about the terms used to name plants, mainly because in some areas, junipers are known as "cedar" - as in the case of Desert White Cedar (Juniperus monosperina). This doesn't mean that J. monosperina wasn't used as a cleansing herb, though; in the Eastern U.S., its relative, Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginia), was used ceremonially. However, in the smudging ceremonies we have seen or conducted ourselves, Western Red Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) and California Cedar Incense (Libocedrus descurrens) were used ... not varieties of juniper.

Cedar is burned while praying either aloud or silently. The prayers rise on the cedar smoke and are carried to the Creator. Cedar is also spread along with sage on the floor of the sweat lodges of some tribes. Cedar branches are brushed in the air to cleanse a home during the House Blessing Ceremony of many Northwest Indian nations. In the Pacific Northwest, the people burn cedar for purification in much the same way as sage - it drives out negative energy; but it also brings in good influences. The spirit of cedar is considered very ancient and wise by Pacific Northwest tribes, and old, downed cedar trees are honored with offerings and prayers.

Sweetgrass

One of the most sacred plants for the Plains Indians, sweetgrass is a tall wild grass with a reddish bas and perfume-like, musty odor. It grows mainly on the eastern side of the Rockies in Montana and adjacent Alberta, Canada. It also shows up in some small areas of Wyoming and South Dakota. Its botanical name is Hierochloe odorata. Some common names for it are Seneca grass, holy grass and vanilla grass. We have been told that a variety of vanilla grass grows in North Central California. But, how similar it is to the Plains variety we don't know.

On the Plains, sweetgrass is usually braided together in bunches as a person's hair is braided, although friends have said they have seen it simply bunched and wrapped in cloth. Either way, it is usually burned by shaving little bits over hot coals or lighting the end and waving it around, letting the smoke spread through the air. This latter method is how we were taught to burn sweetgrass in the sweat lodge - allowing the purifying smoke to get to all parts of the lodge.

We were taught that it was good to burn sweetgrass after the sage or cedar had driven out the bad influences. Sweetgrass brings in the good spirits and the good influences. As with cedar, burning sweetgrass while praying sends prayers up to the Creator in the smoke. High Hollow Horn says in the The Sacred Pipe "This smoke from the sweetgrass will rise up to you, and will spread throughout the universe. Its fragrance will be known by the wingeds, the four-leggeds, and the two leggeds, for we understand that we are all relatives; may all our brothers be tame and not fear us!" Sweetgrass is also put in pipe bundles and medicine bundles along with sage to purify and protect sacred objects.

Sweetgrass is very rare today, its territory severely cut by development, cattle-grazing, and wheat fields - and tradition Indians in the northern Plains are trying to protect the last remaining fields. The best way for most folks to get sweetgrass is to buy it at Native American retail outlets. This gives support to Indians who can help the fields from being depleted.

Smudging

To do a smudging ceremony, burn the clippings of these herbs (dried), rub your hands in the smoke, and then gather the smoke and bring it into your body, or - rub it onto yourself; especially onto any area you feel needs spiritual healing. Keep praying all the while that the unseen powers of the plant will cleanse your spirit. Sometimes, one person will smudge another, or a group of people, using hands - or more often a feather - to lightly brush the smoke over the other person(s). We were taught to look for dark spots in a person's spirit-body. As one California Indian woman told us, she "sees" a person's spirit-body glowing around them, and where there are "dark or foggy parts," she brushes the smoke into these "holes in their spirit-body." This helps to heal the spirit and to "close up" these holes.

Recently we did a "light" house cleansing for a friend. We use the term "light", for this is a relatively simple ceremony as opposed to some that are more lengthy and complicated. Our friend had some serious emotional and relationship problems, and he felt they had left a heavy and dark atmosphere. First, we prayed together to the Creator and to the spirits for help. We then, burned sage, purified ourselves, and took the sage to all the corners, closets, and rooms of the house. We pushed the smoke with our hands to cleanse every bit of space - lingering over dark or cold spots that "felt" uncomfortable.

We used sage first in order to drive out the bad influences. Then we purified ourselves with cedar and, then repeated the cleansing process throughout the house with that. Then sweetgrass was used in the same manner to bring in good influences. All the time we prayed for help in this cleansing. Finally, we took a candle over the whole house and pushed its light into every corner. The People of the Pacific Northwest Coast taught this "lighting-up" of a house to us. We've been doing this type of house cleansing for ten years, and it never fails to "clear the air."

One more note about smudging. It is very popular among many novices to use abalone shells in smudging. There are many Native elders who are pleased to see so many new folds smudging themselves, but - some are concerned that abalone shells are being used when burning the herbs. On the Pacific Northwest Coast, for example, some holy men have said that abalone shells represent Grandmother Ocean, and that they should be used in ceremonies with water, not burning.

In any case, smudging is a ceremony that must be done with care. We are entering into a relationship with the unseen powers of these plants, and with the spirits of the ceremony. As with all good relationships, there has to be respect and honor if the relationship is to work.

The Powwow

Powwows, also called Indian Days or Indian Celebrations, are usually held during July and August on reserves throughout Canada and the United States. Powwows have become a pan-Indian cultural movement throughout North America, and people travel hundreds of miles to attend. Those who travel from one powwow to another all summer long—usually traditional families or champion dancers—are said to be “on the powwow trail.”

Powwows bring together many different First Nations to celebrate their traditional heritage during three days of song and dance. The traditional powwow is conducive to reinforcing social bonds, spiritual beliefs and a common cultural heritage.The powwow setting is usually a huge encampment of tents, trailers and teepees around a main area called an arbor where food and craft booths are set up and where all the activities take place. Dance competitions, special dance demonstrations, naming ceremonies, feasts and giveaways take place each day following a sunrise ceremony. On the last day, the host nation or powwow committee shows gratitude to its visitors by conducting a giveaway.

Grand Entry

This beautiful parade of pride and colour starts off the powwow and each subsequent session of dancing. Preceded by the eagle staff, invited dignitaries and various categories of dancers join in the grand entry and dance to a special song rendered by the drum groups, following the path of the sun through the sky. The lineup is as follows: eagle staff; invited dignitaries; flag-bearers; dignitaries

and princesses; men’s traditional, jingle and fancy dancers; women’s traditional, jingle and fancy dancers; and youth and children in categorical order. Spectators should always stand and remove caps and hats during the grand entry, flag songs and invocation.

Honour Songs

As its name indicates, an honour song honours particular individuals for such things as respect for someone who has passed away, the return of a child to health after an illness or respect for an aged relative. Spectators should always stand and remove caps and hats when an honour song is performed.

The Dances

The Dances

It is believed that most of the dances now being performed at modern celebrations evolved from a dance called the grass dance proper,which might have originated among the Pawnee or Ponca nations of the south central Great Plains. The dance was part of a series of dances connected to a three- and four-day ceremony honouring warriors for valour in victorious military excursions.

The most common dances are the grass dance and the crow hop, which originated among the Crow Nation of Montana; the chicken dance, which comes from the Blackfoot Nation; and the hoop dance, which is a specialty dance that originated

in the southwestern United States. The hoop dance used to be danced only by males but is now also being danced by females. The eagle and buffalo dances are also specialty dances.

It is only within the last 80 years that women have taken an active part in the grass dance. Traditional women’s dances include women’s traditional, women’s fancy and women’s fancy shawl. Women have also adopted an Ojibwa-inspired healing dance known as the jingle dress dance.

Group dancing has also come into vogue and someday may be a main part of these celebrations. All the dances are continually evolving, but dancers try to keep them true to their original form.

Rites Of Passage

Some types of ceremonies appear in almost every culture around the world, although the details vary widely. These common types include ceremonies for births, deaths, marriages and other rites of passage. An important rite of passage for First Nations youth was traditionally the transition from child to adult. The assigns of this passage differed from culture to culture, and between boys and girls. Female Elders generally describe and guided female rites of passage and male Elders did the same for male rites of passage.

In some cultures, a boy’s transition to manhood was marked by hunting or warfare or sometimes a personal event such as going on a spiritual quest. During a spiritual quest an individual sought guidance from a guardian spirit. The rite of passage usually involved a period of a few days in seclusion without food, water or shelter. The person prayed until a vision was received. The Dene Tha’ describe a vision as mendayeh wodekeh ,which means “something appearing in front of someone.” Purification ceremonies were held before and after. In some cultures, elders would later assemble a sacred bundle of objects related to the vision.

In many First Nation cultures, the onset of a girl’s monthly cycle was the event seen to mark her transition to womanhood. Many cultures recognized the event with important ceremonies. Among the Plains Cree, a young woman would spend the first four days of her first monthly cycle in isolation with a grandmother. It was an important time of education and spirituality for the young woman. When the four days were over, her family would celebrate with a community feast and give-away.

In many First Nation cultures, the onset of a girl’s monthly cycle was the event seen to mark her transition to womanhood. Many cultures recognized the event with important ceremonies. Among the Plains Cree, a young woman would spend the first four days of her first monthly cycle in isolation with a grandmother. It was an important time of education and spirituality for the young woman. When the four days were over, her family would celebrate with a community feast and give-away.

Worldview Project

Click to begin your Worldview Project.

Click to begin your Worldview Project.

Rites of Passage

Rites of Passage