Lesson 3: Sociocultural Causes of Abnormal Behaviour

| Site: | MoodleHUB.ca 🍁 |

| Course: | Abnormal Psychology 35 RVS |

| Book: | Lesson 3: Sociocultural Causes of Abnormal Behaviour |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Thursday, 30 October 2025, 1:14 AM |

Table of contents

- Section/Lesson Objectives

- Introduction

- 1 - Behaviour

- 2 - How can Role Changes Lead to Improvements?

- 3 - Societal Influences that Increase Vulnerability

- 4 - Cultural Differences and the Experience of Mental Disorders

- 5 - Social Distance, Hand Gestures, Eye Contact, Facial Expressions

- 6 - Specific Cultural Examples

- 7 - Post-traumatic Stress Disorder - Case Study 2

- 8 - Koro - Case Study 3

- Lesson Review

- Assignment

Section/Lesson Objectives

The student will ...

• Understand and describe how Sociocultural Causes of Abnormal Behaviour interact to cause abnormal behaviour

• Determine the genetic syndrome a person has from evaluating his or her karyotype

• Describe what constitutional liabilities are and how they relate to mental illnesses

• Explain how nutrition affects mental health

• State how physical deprivation can negatively affect mental health

• Give examples of how psychosocial factors affect behaviour

• Describe the Johari window and apply it to different scenarios

• Discuss the effects of bullying

• Differentiate between the way various cultures view abnormalityy

• Understand and describe how sociocultural factors affect mental health

Introduction

Behaviour

For most of us, there is little doubt that social and cultural influences in our lives shape our behaviour patterns from childhood through old age. Some individuals, for reasons of temperament, conditioning, and other personal reasons, may reject the culture in which they have been raised. While avoiding the negative aspects of their cultures, these people may miss the benefits of the positive elements of their cultures. In either case, social and cultural influences may act to increase the likelihood of developing disordered behaviour.

Behaviour

Each cultural group promotes its own patterns of interaction by teaching its children specific behaviours. A result of such training is that members of the group have similar behaviour and similar perspectives. In New Guinea, Margaret Mead found two tribes that were distinctly different despite living in the same general geographical area and despite being of similar racial origin. One tribe, the Arapesh, was kind, peaceful, and co-operative while the other tribe, the Mundugumor, was competitive, revengeful, war-like, and suspicious. These distinct differences between the two tribes appear to be social in origin. Mead also learned about the Tchumbuli tribe. In this tribe the women were the hunters and providers while the men spent their days preening and dressing up in fancy outfits.

Cultural groups also have sub-groups within them. The sub-groups and corresponding roles within the groups are varied. People are expected to act in certain ways depending on whether they are single or married, employed or unemployed, old or young, male or female, parents or childless, etc. For instance, the role of an elderly woman in one culture may differ from that of a religious figure in the same culture.

Please watch this short clip that illustrates how a woman's role in India differs from that in North America.

Other examples include teacher, nurse, police officer, and scientist – they are all influenced by what role each “title” implies within their culture. Even the title of “skateboarder” implies specific vocabulary, clothing, and customs!

Other examples include teacher, nurse, police officer, and scientist – they are all influenced by what role each “title” implies within their culture. Even the title of “skateboarder” implies specific vocabulary, clothing, and customs!

People often advance through a series of roles; they start with the role of the child progressing to students then workers. Most people become spouses and parents before becoming senior citizens. Sometimes social roles are conflicting and uncomfortable. Conformity to social roles can be achieved through reward or punishment. In some parts of the world, a woman is punished if she is seen walking with a male who is not a relative. The role of women in this culture is seen as somewhat oppressive to many North Americans.

Gender roles are also important within cultures. The expectations for men and women within a society have a substantial effect on personality development. Research has shown, however, that low masculinity is associated with maladaptive behaviour and vulnerability to disorder for either gender. Women with low masculinity and high femininity tend to reject opportunities to be in control, an effect Baucom (1983) compares to learned helplessness. Learned helplessness develops when individuals have repeated experiences of failure at tasks or skills, causing them to believe they are not capable when they may simply need to be taught from a different point of view or to break the problem into smaller, achievable subcomponents (K. Brehob, et al, 2004). Learned helplessness is linked to depression.

Brehob, et al, 2004). Learned helplessness is linked to depression.

Related to the terms masculine and feminine is the term androgyny, learned helplessness a combination of andro (male) and gyne (female). It removes the stereotypes we have for each sex and allows people to combine the best traits of both men and women. Traditional concepts of masculinity and femininity put limitations on behavior and how people can express themselves.

In our society, an adult must be independent, assertive, and self-reliant. However, traditional femininity frowns on women behaving in such ways. In addition, an adult male must be sensitive, caring, and attuned to emotional needs.

Traditional masculinity keeps men from expressing these personal needs. Androgyny combines the best of both abilities. It allows adults to be independent yet sensitive; they can be assertive yet open to the wishes of others. In other words, they can be both masculine and feminine. Androgyny facilitates a superior standard of psychological health for the sexes. It unburdens people from sets of narrow views and narrow behaviors. Androgyny expands the horizons of both men and women. It permits people to cope effectively with a wide range of situations.

Traditional masculinity keeps men from expressing these personal needs. Androgyny combines the best of both abilities. It allows adults to be independent yet sensitive; they can be assertive yet open to the wishes of others. In other words, they can be both masculine and feminine. Androgyny facilitates a superior standard of psychological health for the sexes. It unburdens people from sets of narrow views and narrow behaviors. Androgyny expands the horizons of both men and women. It permits people to cope effectively with a wide range of situations.

How does androgyny translate into actual role behaviors or activities? For example, androgyny means a man can manage a business on his own, vacuum the family room, cuddle his children, read them bedtime stories, and do the family laundry. Androgyny means a woman can change the oil in her car, bake a casserole for someone who has been ill, and mow the lawn. Because many of the activities of men and women now overlap because of androgyny, both sexes should have a better understanding and appreciation of each other.

How Can Role Changes Lead to Improvements?

In today’s society, many women are employed outside the home, and men are assuming more household chores than they did in the past. How eager are both sexes to take on new duties? On the average, men do not want to change as much as women do. Because men generally have higher status roles, they gain little by the change and they do not see the need for change as readily.

Today more women are pursuing high status careers, but few men are clamouring for the position of full-time homemaker. Because of our socialization, our first reaction to the male homemaker is likely negative. However, some men are terrific cooks, great domestic planners, and very patient and understanding with children.

of full-time homemaker. Because of our socialization, our first reaction to the male homemaker is likely negative. However, some men are terrific cooks, great domestic planners, and very patient and understanding with children.

Some women make superb business administrators. Modern companies and businesses strive to be more people-friendly. The “Female Advantage” means that feminine qualities bring valuable perspectives to the management of these businesses. The old system focused on hierarchical structures that were goal-oriented and power based following the masculine view. Women often manage people in a collegial way. They gain ideas through consensus, which means power is shared by getting input from all employees.

In addition, women employees may set positive examples for men on how to integrate work and family. Women’s increasing presence in the business field may encourage such positive changes as job-sharing, flexible work hours, and parental leave of absence for both men and women. Rather than precipitating role conflicts, the working mother can be a potential catalyst for a deeper understanding of the roles of husband and wife through shared obligations.

When people become too comfortable, they may begin to reject change. Role conflicts can arise because people are not willing or not able to change when the time is right to do so. The obstacles interfering with change are outdated values, lack of ability to adjust, and uncorrected mistakes that have been passed on by previous generations. When conflict leads to change, people are motivated to examine their roles more carefully and seek ways of changing for the sake of growth.

Role conflicts can produce some useful changes. They may cause us to examine our priorities and our values. They may make us more aware of injustices. The result might be a breakdown of restricted and outdated habits that are not allowing people to progress and find areas of growth and achievement.

In many countries, however, androgyny does not exist and distinct lines between what men do and what women do are evident. Small groups such as the Hutterites in North American communities show well-defined separation of the roles of men and women with respect to work, religion, and parenting.

Societal Influences that Increase Vulnerability

Although people interact in their own specific ways with their environment and have unique blends of roles, expectations, and family dynamics, some situations negatively affect entire cultures despite individual differences of the members. One situation relates to economic status. In general, the lower the socio-economic level, the higher the incidence of abnormal behaviour for some disorders, at least in North American society (Eron & Peterson, 1982). There are many factors that contribute to this statistic. For instance, wealthy people have more resources at their disposal than poor people — from better nutrition to easier access to health care professionals. The wealthy often have distinct advantages over the poor. However, being poor does not mean that a person is destined to develop mental illness. Many mentally healthy people come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and many ill people come from privileged environments.

A second situation that predisposes individuals to mental illness relates to war-like situations.  People who are gentle in nature may be asked to serve their country during periods of conflict – perhaps even killing others and experiencing heinous atrocities and torture. Both victims and veterans of war may need counselling for post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of their experiences.

People who are gentle in nature may be asked to serve their country during periods of conflict – perhaps even killing others and experiencing heinous atrocities and torture. Both victims and veterans of war may need counselling for post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of their experiences.

Difficulties arising from employment also affect many cultures. Not having gainful employment or being dissatisfied with the job that one holds can increase the likelihood of mental illness. Responses related to workplace stress include anxiety, tension, depression, and marital discord. Problems with prejudice and discrimination also are significant in mental illness. Stereotypes and a lack of tolerance or acceptance put undue pressure on the mental health of individuals. As North America becomes more culturally diverse it is extremely important that people (especially health care practitioners) become culturally aware and sensitive. Our North American concept of abnormality has been based primarily on European and American research and so should not be generalized to other cultures. Also important to note is the realization that classification systems are the result of the society in which they were developed. Classification systems must be more inclusive of cultural differences regarding how disorders are displayed.

Difficulties arising from employment also affect many cultures. Not having gainful employment or being dissatisfied with the job that one holds can increase the likelihood of mental illness. Responses related to workplace stress include anxiety, tension, depression, and marital discord. Problems with prejudice and discrimination also are significant in mental illness. Stereotypes and a lack of tolerance or acceptance put undue pressure on the mental health of individuals. As North America becomes more culturally diverse it is extremely important that people (especially health care practitioners) become culturally aware and sensitive. Our North American concept of abnormality has been based primarily on European and American research and so should not be generalized to other cultures. Also important to note is the realization that classification systems are the result of the society in which they were developed. Classification systems must be more inclusive of cultural differences regarding how disorders are displayed.

Cultural Differences and the Experience of Mental Disorders

Individuals from all cultures may have episodes of depression. How each person experiences depression, however, may differ considerably. Some cultures focus more on physical ailments than psychological distress. A depressed person may complain of a stomach ache instead of emotional sadness. In Puerto Rico, people may react to severe stress with symptoms such as heart palpitations and fainting. If a Puerto Rican immigrant displayed this behaviour in western society, he or she may be misdiagnosed (Guaraccia, et al, 1990).

Just as some cultures and sub-cultures place value on showing emotion, other cultures prefer to avoid such displays. In many cultures to ask for help from a mental health practitioner is a sign of weakness. Any emotional problems should be dealt with by family only. In these cultures, discussing personal problems with a stranger is considered disrespectful. Interestingly, certain disorders appear to be the product of specific cultures. For example, eating disorders such as bulimia and anorexia are very much a Western affliction while a syndrome called Koro occurs in some Asian countries. A third case study (summarized from the DSM-III-R Case Book) describing a man with Koro is included at the end of this lesson.

Just as some cultures and sub-cultures place value on showing emotion, other cultures prefer to avoid such displays. In many cultures to ask for help from a mental health practitioner is a sign of weakness. Any emotional problems should be dealt with by family only. In these cultures, discussing personal problems with a stranger is considered disrespectful. Interestingly, certain disorders appear to be the product of specific cultures. For example, eating disorders such as bulimia and anorexia are very much a Western affliction while a syndrome called Koro occurs in some Asian countries. A third case study (summarized from the DSM-III-R Case Book) describing a man with Koro is included at the end of this lesson.

Each culture has its distinct history and set of beliefs. When treating the mentally ill, practitioners need to be aware of these beliefs. For example, does the patient believe that abnormal behaviour is caused by germs, the “evil-eye”, or “too much bile gone to the head”? How do people usually treat disorders? Do they make coriander tea, take a pain killer, or wear a talisman (Adaskin et al., 1990)? The adjustment of immigrants to a new land does increase the risk of many health-related problems. According to Adaskin et al., immigrants often experience much stress; they may not speak the language, they no longer have the support of friends and family from the homeland, and they may experience a loss of status and self-esteem because occupations for which they were trained are often closed to them in North America. Doctors may work as hospital orderlies and teachers as store clerks. These changes greatly challenge their health – both mentally and physically.

When interacting with people of different cultures the differences in social norms can be quite large. In Canada, for example, many European descendents follow informal rules regarding social distance, hand gestures, eye contact, and facial expressions. The information that follows briefly describes what may be observed in Canadian society.

Social Distance, Hand Gestures, Eye Contact, Facial Expressions

Social Distance

When you sit beside someone to talk or work, how far apart do you sit? Usually, you sit close enough so you can talk normally, but far enough apart so you are comfortable. That is an acceptable social distance. Some people break these norms. They are not aware of what an acceptable social distance is and insist on sitting beside you so that you touch each other or talk very close to your face that you see their tonsils. For most people, this is an unacceptable social distance and one person will move to feel more comfortable. However, sometimes the other person moves as well and the problem continues until you tell the person to “back off”. An episode of Seinfeld poked fun at the "close talker".

Video: Seinfeld - The Close Talker.

Hand Gestures

Most of us use our hands when we talk. It is almost part of the conversation. There are certain norms to follow. If a person uses his or her hands too much, you end up watching the hands rather than following the conversation.

Eye Contact

We all follow certain norms when interacting with our eyes. We look at our teachers when they talk. Usually, job interviews are more successful when you look at an interviewer. Parents ask us to look at them when we talk. If you do not follow these norms, your schoolwork could suffer, your job prospects could be fewer, and your parents could lose their temper.

More Facial Expressions

Facial expressions are a part of our daily interactions. People look at your face to get an idea of how you feel about different things. Socially, we learn that certain facial expressions should not be used in front of certain people. These are our norms. For example, you would not stick out your tongue at a police officer, fire fighter, teacher, or parent.

Specific Cultural Examples

Cambodians and Laotians

There are similarities and differences among cultures with respect to how mental illness is viewed. Information in the remainder of this lesson (from Adaskin, et al., 1990) describes how eight cultures view mental illness. Cambodians and Laotians, for example, believe that an individual who has mental health problems brings disgrace and shame to his or her family. As a consequence, mental illness is usually feared and denied. Frequently, individuals suffering from mental health problems are sheltered and hidden by family members until the family can no longer cope. At that point, they may seek professional help. Mental illness may be attributed to evil spirits or “bad karma”. Karma relates to the consequences of deeds committed in a previous life.

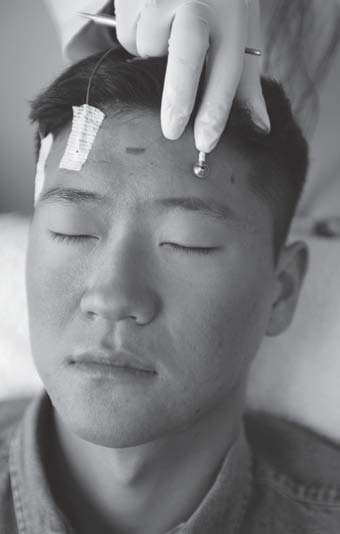

In Southeast Asian culture, where not showing emotion is a virtue and emotional weakness is unacceptable, “somatic complaints represent a cultural means of expressing psychological and emotional distress” (San Duy Nguyen, 1984). Somatic complaints are psychological problems displayed by a variety of physical symptoms such as headaches, insomnia, aches and pains, fatigue, and dizziness. Because the complaints are somatic, people tend to seek help from medical practitioners rather than mental health professionals — and people generally expect to receive medication.

Most mental health problems among Cambodians and Laotians in Canada are linked to severe loss, the difficulty of cultural adjustment upon emigration, and uncertainty about the future. For example, refugees have typically gone through many traumatic experiences in rapid succession with little time to adjust. Often, only after they have begun to settle into their new environment is the full impact of the losses and experiences felt. Some may suffer “survivor guilt”; they may feel they have no right to be alive or to live well when other family members and compatriots have died. Added to the stresses rooted in the past are those of the present: culture shock, language difficulties, social isolation, financial problems, and unemployment or underemployment. Not surprisingly, depression is one of the most common mental health problems among Southeast Asian refugees such as the Cambodians or Laotians.

Central Americans

Similar to the plight of many immigrants, people new to North America from Central America experience stress related to the immigration process, finding work, securing housing, learning English as a second language, and so forth. As time passes, the roles of husband and wife and parent and child begin to diverge from the models familiar in Central America. Many husbands are depressed in the early years of adjustment as they see their traditional family position eroding. In some cases, the wife might find a menial job more easily than the husband and, therefore, she becomes the breadwinner. Although spouses do not habitually discuss intimate topics with each other, if encouraged to do so, they may find that stress is lessened. After a period of adjustment, many individuals find that their depression lifts and anxiety dissipates. For serious mental illness in Central America, people are institutionalized with the expectation that they will never recover or be discharged.

Chinese

The Chinese are more likely to explain the causes of mental illness in terms of external factors or events and the problem is usually presented in the form of somatic complaints. For instance, an elderly lady may say that her heart hurts and may go to the coronary care unit for help when she is actually suffering from depression. Traditionally, different emotions are perceived to be closely related to different organs. For example, anger is associated with the liver, and joy and depression with the heart (Li, 1987). Consequently, clients may seek relief of physical symptoms but not discuss mental health problems. Patients may also attribute their illnesses to supernatural forces such as evil spirits or excessively cold winds. They may not understand the therapies used in Canada; talking about problems may not be an acceptable form of treatment.

Family members have a great influence on how mental health is viewed. Some families may be overprotective of, and give refuge to, their mentally ill members, and the illness becomes a family secret. They may also refuse treatment because they view mental illness as bringing shame on the family. Families may also fear that the mental health problems are genetically inherited. Consequently, people who do have mental health problems may be reluctant to seek help and may delay doing so (Lee, 1986).

Health professionals must find ways to ensure that clients have access to good care but they must also try to be understanding so as to win the family’s trust. Reassurances about strict confidentiality may comfort family members, as might genetic counselling for clients whose families believe that mental health problems are inherited (Lee, 1986).

Iranians

Iranians generally resist seeking help from psychiatrists and other professionals in mental health agencies mainly because of the stigma associated with mental illness. In the educated middle and upper classes, mental illness is often attributed to heredity or physical dysfunction (e.g., disorders of the nervous system). Many people in Iran also attribute mental illness to evil spirits. The majority of families tend to conceal such problems for fear of jeopardizing their children’s chances of marriage (Lipton and Meleis, 1983). Often, a person may be very sick before a psychiatrist’s help is sought.

Iranians are much more comfortable with physical illnesses than with mental illnesses. The first reaction of many Iranians to a diagnosis requiring mental health treatment is denial. For this reason, the advice of neurologists is often sought when emotional health problems arise. For the same reason, medication is more readily accepted than non-pharmaceutical treatments. A very small minority of Iranians with emotional problems may prefer counsellors and psychotherapists to medical doctors.

Japanese

As with many cultures, Japanese culture stigmatizes mental illness. Mental illness is feared and families tend to hide members experiencing mental health problems. They are ashamed to seek help and, therefore, treatment is only sought when individuals become too difficult to handle. Mental illness is often expressed through physical ailments including fatigue, insomnia, stomachaches, and headaches. If pressured to succeed, young people may resort to suicide instead of disappointing their families with failure. If treatment is sought, “talk” is only used to gather information about physical problems, not emotional issues. The individual is encouraged to accept and adjust to his or her situation, not change or modify it.

South Asians

In South Asia, mental illness is sometimes believed to have supernatural causes, particularly spells or curses cast by jealous relatives or acquaintances. These problems are addressed by visiting temples or shrines. Astrologers may also be consulted for a prognosis of the problem. As with many other cultures, symptoms of mental illness are often physical. Because somatic complaints are more acceptable, a person may complain of headaches, stomach-aches, and burning bodily sensations, rather than anxiety or depression. Although mental illness is stigmatized, ill family members are not ignored or rejected, but rather hidden. It is usually when the afflicted person is severely ill that he or she is taken to a health care professional – sometimes after an attempt at suicide.

In some families, the pressure for children to behave one way at home (parental pressure) and another way at school (peer pressure) results in stress, guilt, and depression. Talking about such problems is not usually compatible with South Asian beliefs or expectations. The physician is expected simply to tell the ill person what to do – not help the ill person find his or her own solution.

Vietnamese

For people in Vietnam, mental illness generally means severe disorders – not minor problems such as depression or anxiety. If a person becomes mentally ill, family members feel shame because such individuals are feared and rejected by society. Families care for the affected individual at home. The illness is often linked to the transgressions of ancestors, being born under an “unlucky” star, or malevolent (evil) spirits. An ill person may ask a Buddhist priest for help, or he or she may obtain the services of an exorcist.

Families are hesitant to allow minor problems (such as school-related difficulties) to be treated by a health care professional. Consulting a psychiatrist is equivalent to declaring a family member crazy! Also, to many Buddhists, “all life is suffering,” so people need to learn to cope with stress without burdening others with their problems. It is also not acceptable to talk about family with others. Patients want to be told what to do, not to combine efforts with their doctors to find a solution to their problems. Vietnamese people expect mental health care professionals to be authoritative and direct.

West Indians

Mental illness in the West Indies is stigmatized and viewed with shame. Families keep the mentally ill at home and out of public view. If a person has to be institutionalized, family members are unlikely to visit them. With depression, however, individuals often recover with the support of close friends with whom they can talk. Both physical and psychological pain, however, will be kept hidden from the general public. A show of strength is often presented in social situations because showing weakness is viewed with shame.

One can conclude from the previous information that North American and European cultures have much in common with other cultures regarding how mental illness was, and continues to be, viewed. Fear and stigmatization remain as reactions to the mentally ill. The causes and reasons for mental illness are often complicated and not fully understood. Generally speaking, many people fear what they do not understand.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Pose traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) develops after a trauma occurs that was either experienced or witnessed by the patient. It involves the development of psychological reactions related to the experience such as recurrent, intrusive and distressing recollections of the event. These may be in the form of nightmares, flashbacks and/or hallucinations. The individual may also suffer from depressive symptoms or clinical depression, substance miss-use, and avoidance behaviors.

Video: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Stress Response

In figure 7.1, see a graph showing the stress response that affects humans not suffering from PTSD. Note that within days or weeks, the stress response resolves itself and goes back to the normal level.

Figure 7.1: Acute Stress Response

In figure 7.2, see a graph showing the stress response of an individual that suffers from PTSD. Look at the peak of the graph. You will notice that weeks or months after the stressful event, the body is still impaired by symptoms of the stress response.

Figure 7.2: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Dr. Stan Kutcher, www.teenmentalhealth.org

Case Study 2

|

Description Upon her return home, the woman felt depressed and was unable to return to work due to fear of leaving her apartment. Her symptoms then intensified when her original claim was rejected. She had little interest in doing anything but cooking and cleaning. She felt safe at home, but she became apprehensive when going out. She noted that she did not know why she was apprehensive, but that she did feel better when her husband accompanied her as she did her local errands. When they had to travel to different neighbourhoods, however, she became afraid that his payes (long curled sideburns) and ethnic garments (they were Orthodox Jews) would attract hostile attention from non-Jews. She complained of nightmares regarding her experiences in a concentration camp over forty years ago and found herself dwelling on those memories during the day. The preoccupation was so intense that she was unable to concentrate on activities such as reading. The woman had been an active, competent, and content person before the fire, but she did not understand the cause of all the problems that occurred after the fire. She had often thought about how she would be different if the war had not happened, but she claimed that it was not a major preoccupation for her. When speaking with the psychiatrist, she revealed that she was interred in Auschwitz (a concentration camp) in 1943 at the age of 17. She had been selected for a work crew, told to undress with hundreds of other women, and shoved into a strange-looking empty hall without windows. The room had an odd odour. When the women were eventually transferred to a different part of the camp a few hours later, she learned that the room was a gas chamber. The woman began to cry when she realized that the smell of the burnt synthetic fibres brought back the memory of the gas chamber. This woman’s account is an example of Delayed Type of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. The smell of the burned synthetic fibres triggered a re-living of her Auschwitz experience, but she was unaware of this until her conversation with the psychiatrist. |

Diagnosis This woman’s account is an example of Delayed Type of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. The smell of the burned synthetic fibres triggered a re-living of her Auschwitz experience, but she was unaware of this until her conversation with the psychiatrist. The characteristic symptoms of this disorder are obvious: the stress of being in a concentration camp is definitely outside the range of usual human experience. The trauma is revisited in the form of nightmares, anxiety, and distressing memories. She now avoids situations that remind her of the trauma, has difficulty sleeping, and has lost interest in her usual activities. On Axis IV, the severity of the stress is catastrophic. Although the stressor noted in this Axis usually occurs within the year before evaluation, this is an exception to the rule. The DSM summary is as follows: Axis I: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Delayed Type, Severe Note: Workers’ Compensation agreed to full compensation after the psychiatrist sent the evaluative report.

|

Koro - Case Study 3

|

Description

His first episode occurred when he was 18 years old. He was suddenly convinced that his penis was retracting into his abdomen; he became tense, experienced an elevated heart rate, began to perspire, and felt as if he was about to die. After holding his penis for a few minutes, the episode passed, but since then, he has had similar episodes. Each episode lasts about 15 minutes and happens about twice per year. He did not recall any psychosocial stressors preceding each occurrence. In essence, he had no explanation for the attacks. He claims to have functioned well between episodes and showed no other signs of emotional or social difficulty. He had much shame, however, when discussing the problem with anyone. The patient was born into a middle-class family and was raised by his grandmother. As a boy, he often felt that his penis was much smaller than the other boys’ and was very self-conscious about cleansing in public showers or baths. Other than that, his childhood was rather ordinary. He graduated from school, obtained a job, married at age 26, and had his first child at age 27. A physical examination showed no abnormalities, and other than mild depression, he presented no psychotic symptoms. No personality disturbance was evident. |

Diagnosis The patient is suffering from Koro, a syndrome that appears in the South Pacific. Koro is usually described as an anxiety reaction in which a man fears that his penis will shrink into his abdomen and he will die. A rarer version occurs in women who they believe their external genitals are disappearing. In Western society, the patient may be considered anxious and delusional, but because it is common for family members to share the anxiety and belief that the event is happening (it is a culturally-shared idea), a delusional diagnosis is not made. The main feature of this syndrome is the episodic unrealistic anxiety about a physical symptom without any organic cause. This feature suggests a somatoform disorder. Because the episodes occur only about twice per year (not regularly for at least six months), a diagnosis of undifferentiated somatoform disorder is not possible. The final diagnosis, in Western society, is somatoform disorder not otherwise specified (Axis I), but the Asian term Koro is much more specific. |

Lesson Review

The brain is a fascinating subject, don't you think?

|

To summarize: • Behaviour • How can Role Changes Lead to Improvements? • Societal Influences that Increase Vulnerability • Cultural Differences and the Experience of Mental Disorders • Social Distance, Hand Gestures, Eye Contact, Facial Expressions • Specific Cultural Examples |

Assignment

Complete the following:

1. S2L23Quiz - You may refer to your lesson while you complete this assignment).

2. Unit 2 Research Project (Read the instructions, select a topic and creatively put together your information.

Submit your completed project in the assignment folder provided: Unit2ResearchProject Assignment folder.)

Read the following link on How to Create a Bibliography.

If you are creating your assignment in the google drive, save it as a PDF by following these instructions: Converting a google doc to a PDF. Submit the PDF file in the assignment folder.

A Jewish woman was referred to a psychiatrist for evaluation as part of an appeal regarding a rejected claim from Workers’ Compensation. The married 59 year-old was working as a seamstress when a small fire broke out in the factory and some synthetic fabrics began to smoulder. The fire was quickly extinguished, but not before the fabrics burned, leaving an unpleasant acrid smell. After the fire, the women developed abdominal pain, nausea, and heart palpitations. She was even hospitalized because her physician wanted to rule out a heart condition or asthma. She was released, however, because no evidence of organic pathology was found.

A Jewish woman was referred to a psychiatrist for evaluation as part of an appeal regarding a rejected claim from Workers’ Compensation. The married 59 year-old was working as a seamstress when a small fire broke out in the factory and some synthetic fabrics began to smoulder. The fire was quickly extinguished, but not before the fabrics burned, leaving an unpleasant acrid smell. After the fire, the women developed abdominal pain, nausea, and heart palpitations. She was even hospitalized because her physician wanted to rule out a heart condition or asthma. She was released, however, because no evidence of organic pathology was found.  A man from the People’s Republic of China came to a psychiatric clinic complaining of a shrinking penis. The 28 year-old married man described having repeated episodes for over ten years. Despite being told that his penis had not actually retracted or shrunk, the patient continued to believe that it had. He came in for treatment only because he was told that, if his penis retracted into his abdominal cavity completely, he would die.

A man from the People’s Republic of China came to a psychiatric clinic complaining of a shrinking penis. The 28 year-old married man described having repeated episodes for over ten years. Despite being told that his penis had not actually retracted or shrunk, the patient continued to believe that it had. He came in for treatment only because he was told that, if his penis retracted into his abdominal cavity completely, he would die.