Lesson One - Culture

1.3 Pop Culture, Subculture & Cultural Change

It may seem obvious that there are a multitude of cultural differences between societies in the world. After all, we can easily see that people vary from one society to the next. It is natural that a young woman from rural Kenya would have a very different view of the world from an elderly man in Mumbai—one of the most populated cities in the world. Additionally, each culture has its own internal variations. Sometimes the differences between cultures are not nearly as large as the differences inside cultures however.

High Culture and Popular Culture

Do you prefer listening to opera or hip hop music? Do you like watching horse jumping or NASCAR? Do you read books of poetry or celebrity magazines? In each pair, one type of entertainment is considered high-brow and the other low-brow. Sociologists use the term high culture to describe the pattern of cultural experiences and attitudes that exist in the highest class segments of a society. People often associate high culture with intellectualism, aesthetic taste, political power, and prestige. In North America, high culture also tends to be associated with wealth. Events considered high culture can be expensive and formal—attending a ballet, seeing a play, or listening to a live symphony performance.

The term popular culture refers to the pattern of cultural experiences and attitudes that exist in mainstream society. Popular culture events might include a parade, a baseball game, or a rock concert. Rock and pop music—“pop” short for “popular”—are part of popular culture. In modern times, popular culture is often expressed and spread via commercial media such as radio, television, movies, the music industry, publishers, and corporate-run websites. Unlike high culture, popular culture is known and accessible to most people. You can share a discussion of favourite hockey teams with a new coworker, or comment on American Idol when making small talk in line at the grocery store. But if you tried to launch into a deep discussion on the classical Greek play Antigone, few members of Canadian society today would be familiar with it.

Although high culture may be viewed as superior to popular culture, the labels of “high culture” and “popular culture” vary over time and place. Shakespearean plays, considered pop culture when they were written, are now among our society’s high culture. In the current second “Golden Age of Television,” (the first Golden Age was in the 1950s and 1960s), television programming has gone from typical low-brow situation comedies, soap operas, and crime dramas to the development of “high-quality” series with increasingly sophisticated characters, narratives, and themes (e.g., The Sopranos, True Blood, Dexter, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and Game of Thrones).

Contemporary culture is frequently referred to as a “postmodern culture.” In the era of modern culture, or modernity, the distinction between high culture and popular culture framed the experience of culture in more or less a clear way. The high culture of modernity was often experimental and avant-garde, seeking new and original forms in literature, art, and music to express the elusive, transient, underlying experiences of the modern human condition. It appealed to a limited-but-sophisticated audience. Popular culture was simply the culture of “the people,” immediately accessible and easily digestible, either in the guise of folk traditions or commercialized mass culture. In postmodern culture this distinction begins to break down and it becomes more common to find various sorts of “mash ups” of high and low: serious literature combined with zombie themes, pop music constructed from samples of original “hooks” and melodies, symphony orchestras performing the soundtracks of cartoons, architecture that borrows and blends historical styles, etc. Rock and roll music is the subject of many high-brow histories and academic analyses, just as the common objects of popular culture are transformed and re-presented as high art (e.g., Andy Warhol’s Campbell Soup cans and Marilyn Munro pictures). The dominant sensibility of postmodern popular culture is both playful and ironic, as if the blending and mixing of cultural references (in the television show The Simpsons, for example) is one big “in” joke.

Subculture and Counterculture

A subculture is just as it sounds—a smaller cultural group within a larger culture; people of a subculture are part of the larger culture, but also share a specific identity within a smaller group.

Thousands of subcultures exist within Canada. Ethnic groups share the language, food, and customs of their heritage. Other subcultures are united by shared experiences. Biker culture revolves around a dedication to motorcycles. Some subcultures are formed by members who possess traits or preferences that differ from the majority of a society’s population. Alcoholics Anonymous offers support to those suffering from alcoholism. The body modification community embraces aesthetic additions to the human body, such as tattoos, piercings, and certain forms of plastic surgery. The post-Second World War period was characterized by a series of “spectacular” youth cultures: Teddy boys, beatniks, mods, hippies, skinheads, Rastas, punks, new wavers, ravers, hip-hoppers, and hipsters. But even as members of a subculture band together, they still identify with and participate in the larger society.

Sociologists distinguish subcultures from countercultures, which are a type of subculture that rejects some of the larger culture’s norms and values. In contrast to subcultures, which operate relatively smoothly within the larger society, countercultures might actively defy larger society by developing their own set of rules and norms to live by, sometimes even creating communities that operate outside of greater society.

Cults, a word derived from culture, are also considered counterculture groups. They are usually informal, transient religious groups or movements that deviate from orthodox beliefs and often, but not always, involve allegiance to a charismatic leader. The group Yearning for Zion (YFZ) in Eldorado, Texas, existed outside the mainstream, and the limelight, until its leader was accused of statutory rape and underage marriage. The sect’s formal norms clashed too severely to be tolerated by U.S. law, and in 2008, authorities raided the compound, removing more than 200 women and children from the property.

Cultural Change

As the hipster example illustrates, culture is always evolving. Moreover, new things are added to material culture every day, and they affect nonmaterial culture as well. Cultures change when something new (say, railroads or smartphones) opens up new ways of living and when new ideas enter a culture (say, as a result of travel or globalization).

Innovation: Discovery and Invention

An innovation refers to an object or concept’s initial appearance in society—it’s innovative because it is markedly new. There are two ways to come across an innovative object or idea: discover it or invent it. Discoveries make known previously unknown but existing aspects of reality. In 1610, when Galileo looked through his telescope and discovered Saturn, the planet was already there, but until then, no one had known about it. When Christopher Columbus encountered America, the land was, of course, already well known to its inhabitants. However, Columbus’s discovery was new knowledge for Europeans, and it opened the way to changes in European culture, as well as to the cultures of the discovered lands. For example, new foods such as potatoes and tomatoes transformed the European diet, and horses brought from Europe changed hunting practices of Native American tribes of the Great Plains.

Inventions result when something new is formed from existing objects or concepts—when things are put together in an entirely new manner. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, electric appliances were invented at an astonishing pace. Cars, airplanes, vacuum cleaners, lamps, radios, telephones, and televisions were all new inventions. Inventions may shape a culture when people use them in place of older ways of carrying out activities and relating to others, or as a way to carry out new kinds of activities. Their adoption reflects (and may shape) cultural values, and their use may require new norms for new situations.

Consider the introduction of modern communication technology such as mobile phones and smartphones. As more and more people began carrying these devices, phone conversations no longer were restricted to homes, offices, and phone booths. People on trains, in restaurants, and in other public places became annoyed by listening to one-sided conversations. Norms were needed for cell phone use. Some people pushed for the idea that those who are out in the world should pay attention to their companions and surroundings. However, technology enabled a workaround: texting, which enables quiet communication, and has surpassed phoning as the chief way to meet today’s highly valued ability to stay in touch anywhere, everywhere.

When the pace of innovation increases, it can lead to generation gaps. Technological gadgets that catch on quickly with one generation are sometimes dismissed by a skeptical older generation. A culture’s objects and ideas can cause not just generational but cultural gaps. Material culture tends to diffuse more quickly than nonmaterial culture; technology can spread through society in a matter of months, but it can take generations for the ideas and beliefs of society to change. Sociologist William F. Ogburn coined the term culture lag to refer to this time that elapses between when a new item of material culture is introduced and when it becomes an accepted part of nonmaterial culture (Ogburn 1957).

|

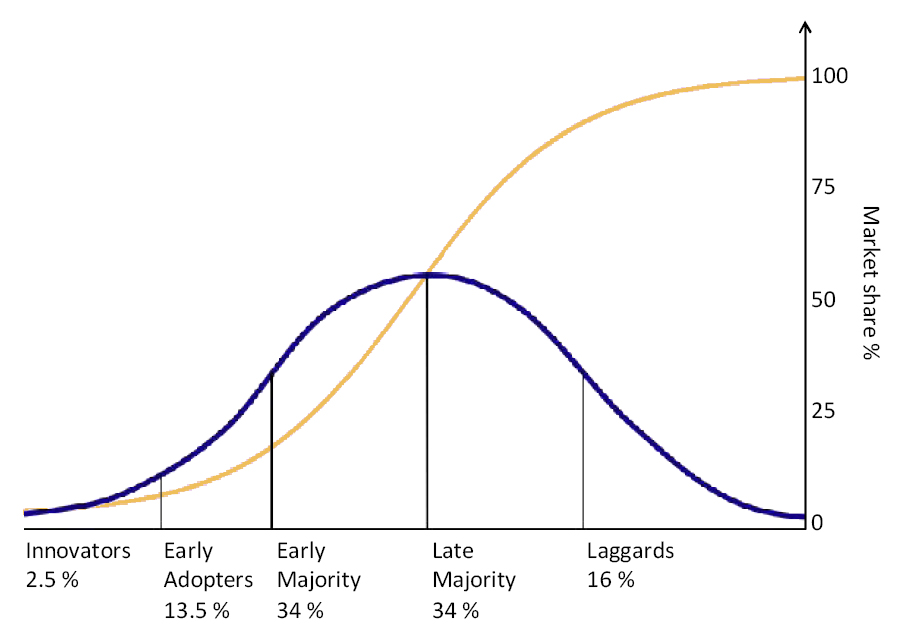

Sociologist Everett Rogers (1962) developed a model of the diffusion of innovations. As consumers |

Culture lag can also cause tangible problems. The industrial economy of North America was built on the assumption that the resources available to exploit and the ability for the environment to sustain industrial activity were unlimited. The concept of sustainable development did not enter into the public imagination until environmental movement of the 1960s and the Limits to Growth report of the Club of Rome in 1972. Today it seems easier to imagine global catastrophe as a result of climate change than it does to implement regulatory changes needed to stem carbon emissions or find alternatives to fossil fuels. There is a lag in conceptualizing solutions to technological problems. Exhausted groundwater supplies, increased air pollution, and climate change are all symptoms of culture lag. Although people are becoming aware of the consequences of overusing resources and of neglecting the integrity of the ecosystems that sustain life, the means to support changes takes time to achieve.

The integration of world markets and technological advances of the last decades have allowed for greater exchange between cultures through the processes of globalization and diffusion. Beginning in the 1970s, Western governments began to deregulate social services while granting greater liberties to private businesses. As a result of this process of neo-liberalization, world markets became dominated by unregulated, international flows of capital investment and new multinational networks of corporations. A global economy emerged to replace nationally based economies. We have since come to refer to this integration of international trade and finance markets as “globalization.” Increased communications and air travel have further opened doors for international business relations, facilitating the flow not only of goods but of information and people as well (Scheuerman 2010). Today, many Canadian companies set up offices in other nations where the costs of resources and labour are cheaper. When a person in Canada calls to get information about banking, insurance, or computer services, the person taking that call may be working in India or Indonesia.

Alongside the process of globalization is diffusion, or, the spread of material and nonmaterial culture. While globalization refers to the integration of markets, diffusion relates a similar process to the integration of international cultures. Middle-class North Americans can fly overseas and return with a new appreciation of Thai noodles or Italian gelato. Access to television and the internet has brought the lifestyles and values portrayed in Hollywood sitcoms into homes around the globe. Twitter feeds from public demonstrations in one nation have encouraged political protesters in other countries. When this kind of diffusion occurs, material objects and ideas from one culture are introduced into another.

|

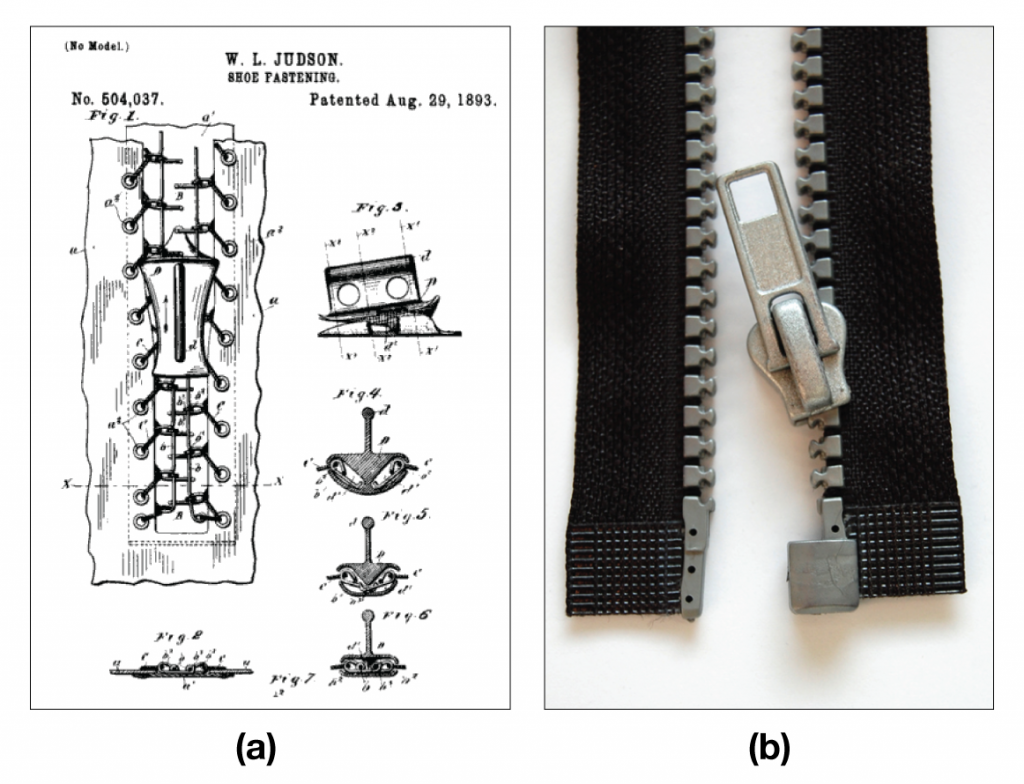

Officially patented in 1893 as the “clasp locker” (left), the zipper did not diffuse through society for many decades. |

Hybridity in cultures is one of the consequences of the increased global flows of capital, people, culture, and entertainment. Hybrid cultures refer to new forms of culture that arise from cross-cultural exchange, especially in the aftermath of the colonial era. On one hand, there are blendings of different cultural elements that had at one time been distinct and locally based: fusion cuisines, mixed martial arts, and New Age shamanism. On the other hand, there are processes of indigenization and appropriation in which local cultures adopt and redefine foreign cultural forms. The classic examples are the cargo cults of Melanesia in which isolated indigenous peoples “re-purposed” Western goods (cargo) within their own ritualistic practices in order to make sense of Westerners’ material wealth. Other examples include Arjun Appadurai’s discussion of how the colonial Victorian game of cricket has been taken over and absorbed as a national passion into the culture of the Indian subcontinent (Appadurai 1996). Similarly, Chinese “duplitecture” reconstructs famous European and North American buildings, or in the case of Hallstatt, Austria, entire villages, in Chinese housing developments (Bosker 2013). As cultural diasporas, or emigrant communities, begin to introduce their cultural traditions to new homelands and absorb the cultural traditions they find there, opportunities for new and unpredictable forms of hybrid culture emerge.