Lesson Three - Media and Technology

3.2 Media and Technology in Society

Making Connections: Real World

Violence in Media and Video Games: Does It Matter?

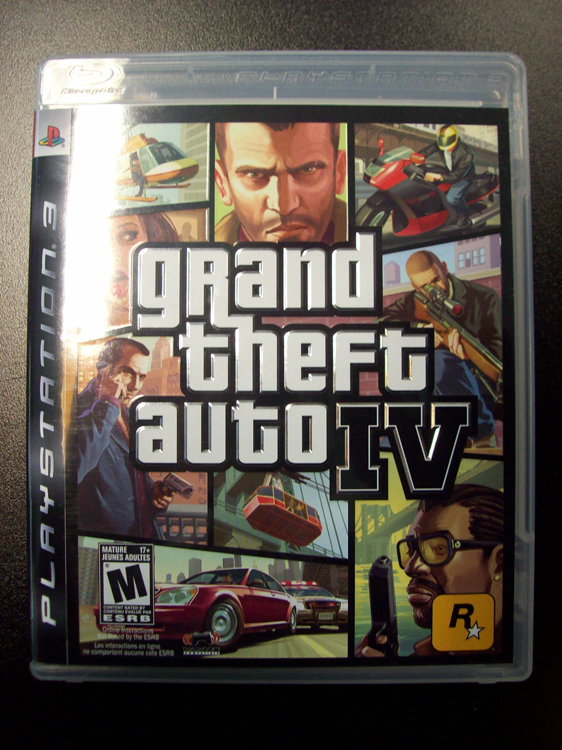

Figure 8.8. One of the most popular video games, Grand Theft Auto, has frequently been at the centre of debate about gratuitous violence in the gaming world. (Photo courtesy of Meddy Garnet/Flickr)

A glance through popular video game and movie titles geared toward children and teens shows the vast spectrum of violence that is displayed, condoned, and acted out. It may hearken back to Popeye and Bluto beating up on each other, or Wile E. Coyote trying to kill and devour the Road Runner, but the graphics and actions have moved far beyond Acme’s cartoon dynamite.

As a way to guide parents in their programming choices, the motion picture industry put a rating system in place in the 1960s. But new media—video games in particular—proved to be uncharted territory. In 1994, the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) set a ratings system for games that addressed issues of violence, sexuality, drug use, and the like. California took it a step further by making it illegal to sell video games to underage buyers. The case led to a heated debate about personal freedoms and child protection, and in 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the California law, stating it violated freedom of speech (ProCon 2012).

With somewhat more muted responses to claims of violations of freedoms, the Canadian rating system through provincial regulation reflects the diversity of interests in connecting media to cultural interests. With the exception of Quebec, most provinces tend to follow the voluntary Canadian Home Video Ratings System established by the Motion Picture Industry-Canada. Quebec has developed internal legislation and policies for motion picture distribution.

Children’s play has often involved games of aggression—from soldiers at war, to cops and robbers, to water-balloon fights at birthday parties. Many articles report on the controversy surrounding the linkage between violent video games and violent behaviour. Are these charges true? Psychologists Anderson and Bushman (2001) reviewed 40-plus years of research on the subject and, in 2003, determined that there are causal linkages between violent video game use and aggression. They found that children who had just played a violent video game demonstrated an immediate increase in hostile or aggressive thoughts, an increase in aggressive emotions, and physiological arousal that increased the chances of acting out aggressive behaviour (Anderson 2003).

Ultimately, repeated exposure to this kind of violence leads to increased expectations regarding violence as a solution, increased violent behavioural scripts, and making violent behaviour more cognitively accessible (Anderson 2003). In short, people who play a lot of these games find it easier to imagine and access violent solutions than nonviolent ones, and are less socialized to see violence as a negative. While these facts do not mean there is no role for video games, it should give players pause. Clearly, when it comes to violence in gaming, it’s not “only a game.”