Lesson Two - Deviance, Crime, and Social Control

2.2 Theoretical Perspectives on Deviance

Figure 7.7. Functionalists believe that deviance plays an important role in society and can be used to challenge people’s views. Protesters, such as these PETA members, often use this method to draw attention to their cause. (Photo courtesy of David Shankbone/flickr)

Why does deviance occur? How does it affect a society? Since the early days of sociology, scholars have developed theories attempting to explain what deviance and crime mean to society. These theories can be grouped according to the three major sociological paradigms: functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and conflict theory.

Functionalism

Sociologists who follow the functionalist approach are concerned with how the different elements of a society contribute to the whole. They view deviance as a key component of a functioning society. Social disorganization theory, strain theory, and cultural deviance theory represent three functionalist perspectives on deviance in society.

Émile Durkheim: The Essential Nature of Deviance

Émile Durkheim believed that deviance is a necessary part of a successful society. One way deviance is functional, he argued, is that it challenges people’s present views (1893). For instance, when black students across the United States participated in “sit-ins” during the civil rights movement, they challenged society’s notions of segregation. Moreover, Durkheim noted, when deviance is punished, it reaffirms currently held social norms, which also contributes to society (1893). Seeing a student given a detention for skipping class reminds other high schoolers that playing hooky isn’t allowed and that they, too, could get a detention.

Social Disorganization Theory

Developed by researchers at the University of Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s, social disorganization theory asserts that crime is most likely to occur in communities with weak social ties and the absence of social control. In a certain way, this is the opposite of Durkheim’s thesis. Rather than deviance being a force that reinforces moral and social solidarity, it is the absence of moral and social solidarity that provides the conditions for social deviance to emerge.

Early Chicago School sociologists used an ecological model to map the zones in Chicago where high levels of social problem were concentrated. During this period, Chicago was experiencing a long period of economic growth, urban expansion, and foreign immigration. They were particularly interested in the zones of transition between established working class neighbourhoods and the manufacturing district. The city’s poorest residents tended to live in these transitional zones, where there was a mixture of races, immigrant ethnic groups, and non-English languages, and a high rate of influx as people moved in and out. They proposed that these zones were particularly prone to social disorder because the residents had not yet assimilated to the American way of life. When they did assimilate they moved out, making it difficult for a stable social ecology to become established there.

Figure 7.8. Proponents of social disorganization theory believe that individuals who grow up in impoverished areas are more likely to participate in deviant or criminal behaviours. (Photo courtesy of Apollo 1758/Wikimedia Commons)

Social disorganization theory points to broad social factors as the cause of deviance. A person is not born a criminal, but becomes one over time, often based on factors in his or her social environment. This theme was taken up by Travis Hirschi’s control theory (1969). According to Hirschi, social control is directly affected by the strength of social bonds. Many people would be willing to break laws or act in deviant ways to reap the rewards of pleasure, excitement, and profit, etc. if they had the opportunity. Those who do have the opportunity are those who are only weakly controlled by social restrictions. Similar to Durkheim’s theory of anomie, deviance is seen to result where feelings of disconnection from society predominate. Individuals who believe they are a part of society are less likely to commit crimes against it. Hirschi (1969) identified four types of social bonds that connect people to society:

- Attachment measures our connections to others. When we are closely attached to people, we worry about their opinions of us. People conform to society’s norms in order to gain approval (and prevent disapproval) from family, friends, and romantic partners.

- Commitment refers to the investments we make in conforming to conventional behaviour. A well-respected local businesswoman who volunteers at her synagogue and is a member of the neighbourhood block organization has more to lose from committing a crime than a woman who does not have a career or ties to the community. There is a cost/benefit calculation in the decision to commit a crime in which the costs of being caught are much higher for some than others.

- Similarly, levels of involvement, or participation in socially legitimate activities, lessen a person’s likelihood of deviance. Children who are members of Little League baseball teams have fewer family crises.

- The final bond, belief, is an agreement on common values in society. If a person views social values as beliefs, he or she will conform to them. An environmentalist is more likely to pick up trash in a park because a clean environment is a social value to that person.

An individual who grows up in a poor neighbourhood with high rates of drug use, violence, teenage delinquency, and deprived parenting is more likely to become a criminal than an individual from a wealthy neighbourhood with a good school system and families who are involved positively in the community. The mutual dependencies and complex relationships that form the basis of a healthy “ecosystem” or social control do not get established. Research into social disorganization theory can greatly influence public policy. For instance, studies have found that children from disadvantaged communities who attend preschool programs that teach basic social skills are significantly less likely to engage in criminal activity. In the same way, the Chicago School sociologists focused their efforts on community programs designed to help assimilate new immigrants into North American culture. However, in proposing that social disorganization is essentially a moral problem—that it is shared moral values that hold communities together and prevent crime and social disorder—questions about economic inequality, racism, and power dynamics do not get asked.

Robert Merton: Strain Theory

Sociologist Robert Merton agreed that deviance is, in a sense, a normal behaviour in a functioning society, but he expanded on Durkheim’s ideas by developing strain theory, which notes that access to socially acceptable goals plays a part in determining whether a person conforms or deviates. From birth, we are encouraged to achieve the goal of financial success. A woman who attends business school, receives her MBA, and goes on to make a million-dollar income as CEO of a company is said to be a success. However, not everyone in our society stands on equal footing. A person may have the socially acceptable goal of financial success but lack a socially acceptable way to reach that goal. According to Merton’s theory, an entrepreneur who can not afford to launch his own company may be tempted to embezzle from his employer for start-up funds. The discrepancy between the reality of structural inequality and the high cultural value of economic success creates a strain that has to be resolved by some means. Merton defined five ways that people adapt to this gap between having a socially accepted goal but no socially accepted way to pursue it.

- Conformity: The majority of people in society choose to conform and not to deviate. They pursue their society’s valued goals to the extent that they can through socially accepted means.

- Innovation: Those who innovate pursue goals they cannot reach through legitimate means by instead using criminal or deviant means.

- Ritualism: People who ritualize lower their goals until they can reach them through socially acceptable ways. These “social ritualists” focus on conformity to the accepted means of goal attainment while abandoning the distant, unobtainable dream of success.

- Retreatism: Others retreat from the role strain and reject both society’s goals and accepted means. Some beggars and street people have withdrawn from society’s goal of financial success. They drop out.

- Rebellion: A handful of people rebel, replacing a society’s goals and means with their own. Rebels seek to create a greatly modified social structure in which provision would be made for closer correspondence between merit, effort, and reward.

As many youth from poor backgrounds are exposed to the high value placed on material success in capitalist society but face insurmountable odds to achieving it, turning to illegal means to achieve success is a rational, if deviant, solution.

Critical Sociology

Critical sociology looks to social and economic factors as the causes of crime and deviance. Unlike functionalists, conflict theorists don’t see these factors as necessary functions of society, but as evidence of inequality in the system. As a result of inequality, many crimes can be understood as crimes of accommodation, or ways in which individuals cope with conditions of oppression (Quinney 1977). Predatory crimes like break and enters, robbery, and drug dealing are often simply economic survival strategies. Personal crimes like murder, assault, and sexual assault are products of the stresses and strains of living under stressful conditions of scarcity and deprivation. Defensive crimes like economic sabotage, illegal strikes, civil disobedience, and eco-terrorism are direct challenges to social injustice. The analysis of critical sociologists is not meant to excuse or rationalize crime, but to locate its underlying sources at the appropriate level so that they can be addressed effectively.

Critical sociologists do not see the normative order and the criminal justice system as simply neutral or “functional” with regard to the collective interests of society. Institutions of normalization and the criminal justice system have to be seen in context as mechanisms that actively maintain the power structure of the political-economic order. The rich, the powerful, and the privileged have unequal influence on who and what gets labelled deviant or criminal, particularly in instances when their privilege is being challenged. As capitalist society is based on the institution of private property, for example, it is not surprising that theft is a major category of crime. By the same token, when street people, addicts, or hippies drop out of society, they are labelled deviant and are subject to police harassment because they have refused to participate in productive labour.

On the other hand, the ruthless and sometimes sociopathic behaviour of many business people and politicians, otherwise regarded as deviant according to the normative codes of society, is often rewarded or regarded with respect. In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite, a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favour of a privileged few who manipulate them to stay on top. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power. Mills’s theories explain why celebrities such as Chris Brown and Paris Hilton, or once-powerful politicians such as Eliot Spitzer and Tom DeLay, can commit crimes with little or no legal retribution.

Crime and Social Class

While functionalist theories often emphasize crime and deviance associated with the underprivileged, there is in fact no clear evidence that crimes are committed disproportionately by the poor or lower classes. There is an established association between the underprivileged and serious street crimes like armed robbery and assault, but these do not constitute the majority of crimes in society, nor the most serious crimes in terms of their overall social, personal, and environmental effects. On the other hand, crimes committed by the wealthy and powerful remain an underpunished and costly problem within society. White-collar or corporate crime refers to crimes committed by corporate employees or owners in the pursuit of profit or other organization goals. They are more difficult to detect because the transactions take place in private and are more difficult to prosecute because the criminals can secure expert legal advice on how to bend the rules.

In the United States it has been estimated that the yearly value of all street crime is roughly 5 percent of the value of corporate crime or “suite crime” (Snider 1994). Comparable data is not compiled in Canada; however, the Canadian Department of Justice reported that the total value of property stolen or damaged due to property crime in 2008 was an estimated $5.8 billion (Zhang 2008), which would put the cost of corporate crime at $116 billion (if the ratio holds in Canada). For example, Canadians for Tax Fairness estimates that wealthy Canadians have a combined total of $170 billion concealed in untaxed offshore tax havens (Tencer 2013). “Tax haven use has robbed at least $7.8 billion in tax revenues from Canada” (Howlett 2013).

PricewaterhouseCoopers reports that 36 percent of Canadian companies were subject to white-collar crime in 2013 (theft, fraud, embezzlement, cybercrime). One in ten lost $5 million or more (McKenna 2014). Recent high-profile Ponzi scheme and investment frauds run into tens of millions of dollars each, destroying investors retirement savings. Vincent Lacroix was sentenced to 13 years in prison in 2009 for defrauding investors of $115 million; Earl Jones was sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2010 for defrauding investors of $50 million; Weizhen Tang was sentenced to 6 years in prison in 2013 for defrauding investors of $52 million. These were highly publicized cases in which jail time was demanded by the public (although as nonviolent offenders the perpetrators are eligible for parole after serving one-sixth of their sentence). However, in 2011–2012 prison sentences were nearly twice as likely for the typically lower-class perpetrators of break and enters (59 percent) as they were for typically middle- and upper-class perpetrators of fraud (35 percent) (Boyce 2013).

This imbalance based on class power can also be put into perspective with respect to homicide rates (Samuelson 2000). In 2005, there were 658 homicides in Canada recorded by police, an average of 1.8 a day. This is an extremely serious crime, which merits the attention given to it by the criminal justice system. However, in 2005 there were also 1,097 workplace deaths that were, in principle, preventable. Canadians work on average 230 days a year, meaning that there were on average five workplace deaths a day for every working day in 2005 (Sharpe and Hardt 2006). Estimates from the United States suggest that only one-third of on-the-job deaths and injuries can be attributed to worker carelessness (Samuelson 2000).

In 2005, 51 percent of the workplace deaths in Canada were due to occupational diseases like cancers from exposure to asbestos (Sharpe and Hardt 2006). The Ocean Ranger oil-rig collapse that killed 84 workers off Newfoundland in 1982 and the Westray mine explosion that killed 26 workers in Nova Scotia in 1992 were due to design flaws and unsafe working conditions that were known to the owners. However, whereas corporations are prosecuted for regulatory violations governing health and safety, it is rare for corporations or corporate officials to be prosecuted for the consequences of those violations. “For example, a company would be fined for not installing safety bolts in a construction crane, but not prosecuted for the death of several workers who were below the crane when it collapsed (as in a recent case in Western Canada)” (Samuelson 2000).

Corporate crime is arguably a more serious type of crime than street crime, and yet white-collar criminals are treated relatively leniently. Fines, when they are imposed, are typically absorbed as a cost of doing business and passed on to consumers, and many crimes, from investment fraud to insider trading and price fixing, are simply not prosecuted. From a critical sociology point of view, this is because white-collar crime is committed by elites who are able to use their power and financial resources to evade punishment. Here are some examples:

- In the United States, not a single criminal charge was filed against a corporate executive after the financial mismanagement of the 2008 financial crisis. The American Security and Exchange Commission levied a total of $2.73 billion in fines and out-of-court settlements, but the total cost of the financial crisis was estimated to be between $6 and $14 trillion (Pyke 2013).

- In Canada, three Nortel executives were charged by the RCMP’s Integrated Market Enforcement Team (IMET) with fraudulently altering accounting procedures in 2002–2003 to make it appear that Nortel was running a profit (thereby triggering salary bonuses for themselves totalling $12 million), but were acquitted in 2013. The accounting procedures were found to inflate the value of the company, but the intent to defraud could not be proven. The RCMP’s IMET, implemented in 2003 to fight white-collar crime, managed only 11 convictions over the first nine years of its existence (McFarland and Blackwell 2013).

- Enbridge’s 20,000 barrel spill of bitumen (tar sands) oil into the Kalamazoo River, Michigan, in 2010 was allowed to continue for 17 hours and involved twice re-pumping bitumen into the pipeline. The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board report noted that the spill was the result of “pervasive organizational failures,” and documents revealed that the pipeline operators were more concerned about getting home for the weekend than solving the problem (Rusnell 2012). No criminal charges were laid.

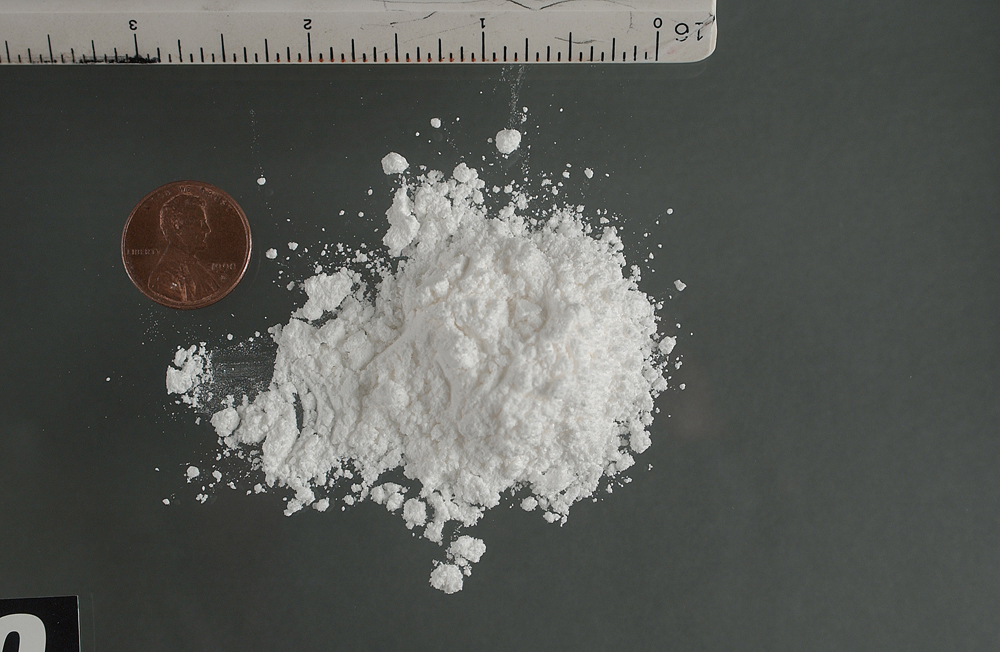

Figure 7.9. From 1986 until 2010, the punishment for possessing crack, a “poor person’s drug,” was 100 times stricter than the punishment for cocaine use, a drug favoured by the wealthy. (Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Feminist Contributions

Women who are regarded as criminally deviant are often seen as being doubly deviant. They have broken the laws but they have also broken gender norms about appropriate female behaviour, whereas men’s criminal behaviour is seen as consistent with their aggressive, self-assertive character. This double standard also explains the tendency to medicalize women’s deviance, to see it as the product of physiological or psychiatric pathology. For example, in the late 19th century, kleptomania was a diagnosis used in legal defences that linked an extreme desire for department store commodities with various forms of female physiological or psychiatric illness. The fact that “good” middle- and upper-class women, who were at that time coincidentally beginning to experience the benefits of independence from men, would turn to stealing in department stores to obtain the new feminine consumer items on display there, could not be explained without resorting to diagnosing the activity as an illness of the “weaker” sex (Kramar 2011).

Feminist analysis focuses on the way gender inequality influences the opportunities to commit crime and the definition, detection, and prosecution of crime. In part the gender difference revolves around patriarchal attitudes toward women and the disregard for matters considered to be of a private or domestic nature. For example, until 1969, abortion was illegal in Canada, meaning that hundreds of women died or were injured each year when they received illegal abortions (McLaren and McLaren 1997). It was not until the Supreme Court ruling in 1988 that struck down the law that it was acknowledged that women are capable of making their own choice, in consultation with a doctor, about the procedure. Similarly, until the 1970s, two major types of criminal deviance were largely ignored or were difficult to prosecute as crimes: sexual assault and spousal assault.

Through the 1970s, women worked to change the criminal justice system and establish rape crisis centres and battered women’s shelters, bringing attention to domestic violence. In 1983 the Criminal Code was amended to replace the crimes of rape and indecent assault with a three-tier structure of sexual assault (ranging from unwanted sexual touching that violates the integrity of the victim to sexual assault with a weapon or threats or causing bodily harm to aggravated sexual assault that results in wounding, maiming, disfiguring, or endangering the life of the victim) (Kong et al. 2003). Johnson (1996) reported that in the mid-1990s, when violence against women began to be surveyed systematically in Canada, 51 percent of Canadian women had been the subject to at least one sexual or physical assault since the age of 16.

The goal of the amendments was to emphasize that sexual assault is an act of violence, not a sexual act. Previously, rape had been defined as an act that involved penetration and was perpetrated against a woman who was not the wife of the accused. This had excluded spousal sexual assault as a crime and had also exposed women to secondary victimization by the criminal justice system when they tried to bring charges. Secondary victimization occurs when the women’s own sexual history and her willingness to consent are questioned in the process of laying charges and reaching a conviction, which as feminists pointed out, increased victims’ reluctance to lay charges.

In particular feminists challenged the twin myths of rape that were often the subtext of criminal justice proceedings presided over largely by men (Kramar 2011). The first myth is that women are untrustworthy and tend to lie about assault out of malice toward men, as a way of getting back at them for personal grievances. The second myth, is that women will say “no” to sexual relations when they really mean “yes.” Typical of these types of issues was the judge’s comment in a Manitoba Court of Appeal case in which a man plead guilty to sexually assaulting his twelve- or thirteen-year-old babysitter:

The girl, of course, could not consent in the legal sense, but nonetheless was a willing participant. She was apparently more sophisticated than many her age and was performing many household tasks including babysitting the accused’s children. The accused and his wife were somewhat estranged (cited in Kramar 2011).

Because the girl was willing to perform household chores in place of the man’s estranged wife, the judge assumed she was also willing to engage in sexual relations. In order to address these types of issue, feminists successfully pressed the Supreme Court to deliver rulings that restricted a defence attorney’s access to a victim’s medical and counselling records and rules of evidence were changed to prevent a woman’s past sexual history being used against her. Consent to sexual discourse was redefined as what a woman actually says or does, not what the man believes to be consent. Feminists also argued that spousal assault was a key component of patriarchal power. Typically it was hidden in the household and largely regarded as a private, domestic matter in which police were reluctant to get involved.

Interestingly women and men report similar rates of spousal violence—in 2009, 6 percent had experienced spousal violence in the previous five years—but women are more likely to experience more severe forms of violence including multiple victimizations and violence leading to physical injury (Sinha 2013). In order to empower women, feminists pressed lawmakers to develop zero-tolerance policies that would support aggressive policing and prosecution of offenders. These policies oblige police to lay charges in cases of domestic violence when a complaint is made, whether or not the victim wished to proceed with charges (Kramar 2011).

In 2009, 84 percent of violent spousal incidents reported by women to police resulted in charges being laid. However, according to victimization surveys only 30 percent of actual incidents were reported to police. The majority of women who did not report incidents to the police stated that they dealt with them in another way, felt they were a private matter, or did not think the incidents were important enough to report. A significant proportion, however, did not want anyone to find out (44 percent), did not want their spouse to be arrested (40 percent), or were too afraid of their spouse (19 percent) (Sinha 2013).

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism is a theoretical approach that can be used to explain how societies and/or social groups come to view behaviours as deviant or conventional. The key component of this approach is to emphasize the social processes through which deviant activities and identities are socially defined and then “lived” as deviant. Social groups and authorities create deviance by first making the rules and then applying them to people who are thereby labelled as outsiders (Becker 1963). Deviance is not an intrinsic quality of individuals but is created through the social interactions of individuals and various authorities. Deviance is something that, in essence, is learned.

Deviance as Learned Behaviour

In the early 1900s, sociologist Edwin Sutherland sought to understand how deviant behaviour developed among people. Since criminology was a young field, he drew on other aspects of sociology including social interactions and group learning (Laub 2006). His conclusions established differential association theory, stating that individuals learn deviant behaviour from those close to them who provide models of and opportunities for deviance. According to Sutherland, deviance is less a personal choice and more a result of differential socialization processes. A tween whose friends are sexually active is more likely to view sexual activity as acceptable.

A classic study of differential association is Howard Becker’s study of marijuana users in the jazz club scene of Chicago in the 1950s (Becker 1953). Becker paid his way through graduate studies by performing as a jazz pianist and took the opportunity to study his fellow musicians. He conducted 50 interviews and noted that becoming a marijuana user involved a social process of initiation into a deviant role that could not be accounted for by either the physiological properties of marijuana or the psychological needs (for escape, fantasy, etc.) of the individual. Rather the “career” of the marijuana user involved a sequence of changes in attitude and experience learned through social interactions with experienced users before marijuana could be regularly smoked for pleasure.

Regular marijuana use was a social achievement that required the individual to pass through three distinct stages. Failure to do so meant that the individual would not assume the deviant role as a regular user of marijuana. Firstly, individuals had to learn to smoke marijuana in a way that would produce real effects. Many first-time users do not feel the effects. If they are not shown how to inhale the smoke or how much to smoke, they might not feel the drug had any effect on them. Their “career” might end there if they are not encouraged by others to persist. Secondly, they had to learn to recognize the effects of “being high” and connect them with drug use.

Although people might display different symptoms of intoxication—feeling hungry, elated, rubbery, etc.—they might not recognize them as qualities associated with the marijuana or even recognize them as different at all. Through listening to experienced users talk about their experiences, novices are able to locate the same type of sensations in their own experience and notice something qualitatively different going on. Thirdly, they had to learn how to enjoy the sensations: they had to learn how to define the situation of getting high as pleasurable. Smoking marijuana is not necessarily pleasurable and often involves uncomfortable experiences like loss of control, impaired judgment, distorted perception, and paranoia. Unless the experiences can be redefined as pleasurable the individual will not become a regular user. Often experienced users are able to coach novices through difficulties and encourage them by telling them they will learn to like it. It is through differential association with a specific set of individuals that a person learns and assumes a deviant role. The role needs to be learned and its value recognized before it can become routine or normal for the individual.

Labelling Theory

Although all of us violate norms from time to time, few people would consider themselves deviant. Often, those who do, however, have gradually come to believe they are deviant because they been labelled “deviant” by society. Labelling theory examines the ascribing of a deviant behaviour to another person by members of society. Thus, what is considered deviant is determined not so much by the behaviours themselves or the people who commit them, but by the reactions of others to these behaviours. As a result, what is considered deviant changes over time and can vary significantly across cultures. As Becker put it, “deviance is not a quality of the act the person commits, but rather a consequence of the application by others of rules and sanctions to the offender. The deviant is one to whom the label has successfully been applied; deviant behaviour is behaviour people so label” (1963).

It is important to note that labelling theory does not address the initial motives or reasons for the rule-breaking behaviour, which might be unknowable, but the importance of its social consequences. It does not attempt to answer the question why people break the rules or why they are deviant so much as why particular acts or particular individuals are labelled deviant while others are not. How do certain acts get labelled deviant and what are the consequences?

Sociologist Edwin Lemert expanded on the concepts of labelling theory, identifying two types of deviance that affect identity formation. Primary deviance is a violation of norms that does not result in any long-term effects on the individual’s self-image or interactions with others. Speeding is a deviant act, but receiving a speeding ticket generally does not make others view you as a bad person, nor does it alter your own self-concept. Individuals who engage in primary deviance still maintain a feeling of belonging in society and are likely to continue to conform to norms in the future.

Sometimes, in more extreme cases, primary deviance can morph into secondary deviance. Secondary deviance occurs when a person’s self-concept and behaviour begin to change after his or her actions are labelled as deviant by members of society. The person may begin to take on and fulfill the role of a “deviant” as an act of rebellion against the society that has labelled that individual as such. For example, consider a high school student who often cuts class and gets into fights. The student is reprimanded frequently by teachers and school staff, and soon enough, develops a reputation as a “troublemaker.” As a result, the student starts acting out even more and breaking more rules, adopting the “troublemaker” label and embracing this deviant identity.

Secondary deviance can be so strong that it bestows a master status on an individual. A master status is a label that describes the chief characteristic of an individual. Some people see themselves primarily as doctors, artists, or grandfathers. Others see themselves as beggars, convicts, or addicts. The criminal justice system is ironically one of the primary agencies of socialization into the criminal “career path.” The labels “juvenile delinquent” or “criminal” are not automatically applied to individuals who break the law. A teenager who is picked up by the police for a minor misdemeanour might be labelled as a “good kid” who made a mistake and then released after a stern talking to, or he or she might be labelled a juvenile delinquent and processed as a young offender. In the first case, the incident may not make any impression on the teenager’s personality or on the way others react to him or her. In the second case, being labelled a juvenile delinquent sets up a set of responses to the teenager by police and authorities that lead to criminal charges, more severe penalties, and a process of socialization into the criminal identity.

In detention in particular, individuals learn how to assume the identity of serious offenders as they interact with hardened, long-term inmates within the prison culture (Wheeler 1961). The act of imprisonment itself modifies behaviour, to make individuals more criminal. Aaron Cicourel’s research in the 1960s showed how police used their discretionary powers to label rule-breaking teenagers who came from homes where the parents were divorced as juvenile delinquents and to arrest them more frequently than teenagers from intact homes (Cicourel 1968). Judges were also found to be more likely to impose harsher penalties on teenagers from divorced families.

Unsurprisingly, Cicourel noted that subsequent research conducted on the social characteristics of teenagers who were charged and processed as juvenile delinquents found that children from divorced families were more likely to be charged and processed. Divorced families were seen as a cause of youth crime. This set up a vicious circle in which the research confirmed the prejudices of police and judges who continued to label, arrest, and convict the children of divorced families disproportionately. The labelling process acted as a self-fulfilling prophecy in which police found what they expected to see.