Lesson Three - Media and Technology

3.1 Technology Today

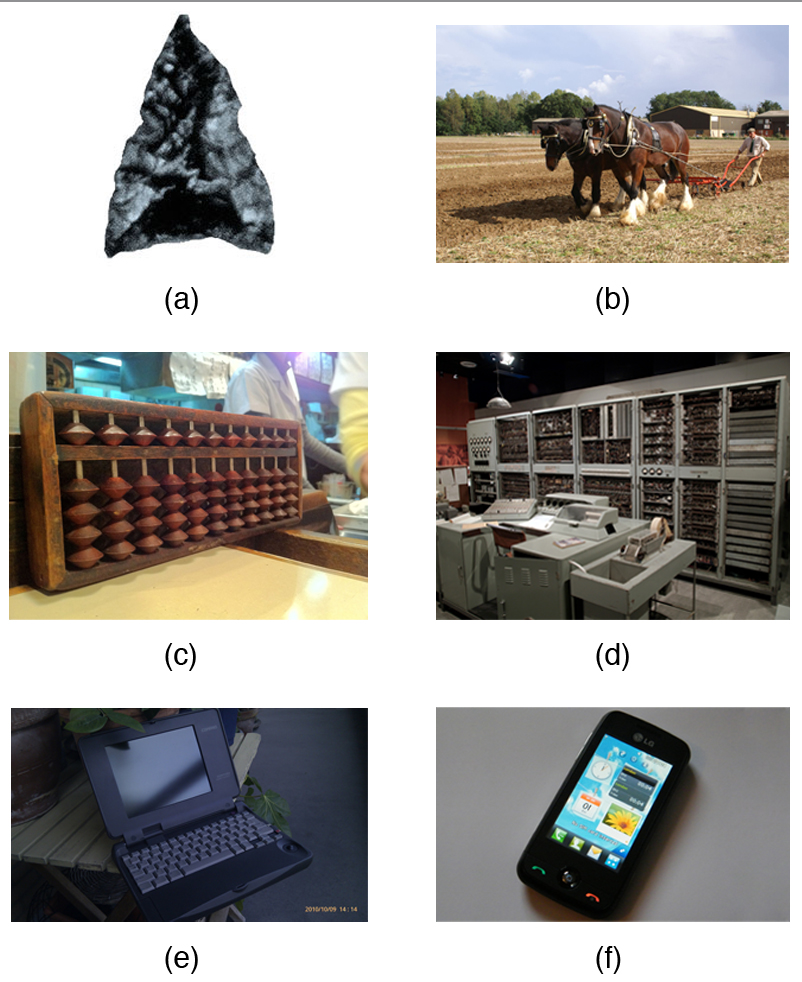

Figure 8.2. Technology is the application of science to address the problems of daily life, from hunting tools and agricultural advances, to manual and electronic ways of computing, to today’s tablets and smartphones. (Photo (a) courtesy of Wikimedia Commons; Photo (b) courtesy Martin Pettitt/flickr; Photo (c) courtesy Whitefield d./flickr; Photo (d) courtesy Andrew Parnell/flickr; Photo (e) courtesy Jemimus/flickr; Photo (f) courtesy digitpedia/flickr)

It is easy to look at the latest sleek tiny Apple product and think that technology is only recently a part of our world. But from the steam engine to the most cutting-edge robotic surgery tools, technology describes the application of science to address the problems of daily life. We might look back at the enormous and clunky computers of the 1970s that had about as much storage as an iPod Shuffle and roll our eyes in disbelief. But chances are 30 years from now our skinny laptops and MP3 players will look just as archaic.

What Is Technology?

While most people probably picture computers and cell phones when the subject of technology comes up, technology is not merely a product of the modern era. For example, fire and stone tools were important forms of technology developed during the Stone Age. Just as the availability of digital technology shapes how we live today, the creation of stone tools changed how premodern humans lived and how well they ate. From the first calculator, invented in 2400 BCE in Babylon in the form of an abacus, to the predecessor of the modern computer, created in 1882 by Charles Babbage, all of our technological innovations are advancements on previous iterations. And indeed, all aspects of our lives today are influenced by technology. In agriculture, the introduction of machines that can till, thresh, plant, and harvest greatly reduced the need for manual labour, which in turn meant there were fewer rural jobs, which led to the urbanization of society, as well as lowered birthrates because there was less need for large families to work the farms. In the criminal justice system, the ability to ascertain innocence through DNA testing has saved the lives of people on death row. The examples are endless: technology plays a role in absolutely every aspect of our lives.

Technological Inequality

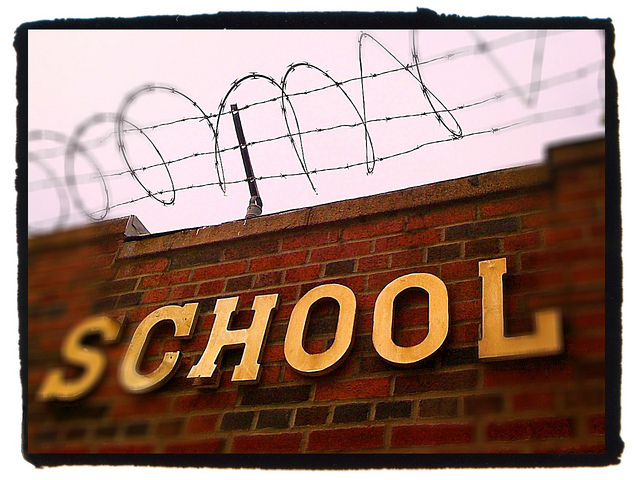

Figure 8.3. Some schools sport cutting-edge computer labs, while others sport barbed wire. Is your academic technology at the cusp of innovation, relatively disadvantaged, or somewhere in between? (Photo courtesy of Carlos Martinez/flickr)

As with any improvement to human society, not everyone has equal access. Technology, in particular, often creates changes that lead to ever greater inequalities. In short, the gap gets wider faster. This technological stratification has led to a new focus on ensuring better access for all.

There are two forms of technological stratification. The first is differential class-based access to technology in the form of the digital divide. This digital divide has led to the second form, a knowledge gap, which is, as it sounds, an ongoing and increasing gap in information for those who have less access to technology. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines the digital divide as “the gap between individuals, households, businesses and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard to both their opportunities to access information and communication technology (ICTs) and to their use of the Internet for a wide variety of activities.” (OECD 2001 p.5) For example, students in well-funded schools receive more exposure to technology than students in poorly funded schools. Those students with more exposure gain more proficiency, making them far more marketable in an increasingly technology-based job market, leaving our society divided into those with technological knowledge and those without. Even as we improve access, we have failed to address an increasingly evident gap in e-readiness, the ability to sort through, interpret, and process knowledge (Sciadas 2003).

Since the beginning of the millennium, social science researchers have tried to bring attention to the digital divide, the uneven access to technology along race, class, and geographic lines. The term became part of the common lexicon in 1996, when then U.S. Vice-President Al Gore used it in a speech. In part, the issue of the digital divide had to do with communities that received infrastructure upgrades that enabled high-speed internet access, upgrades that largely went to affluent urban and suburban areas, leaving out large swaths of the country.

At the end of the 20th century, technology access was also a big part of the school experience for those whose communities could afford it. Early in the millennium, poorer communities had little or no technology access, while well-off families had personal computers at home and wired classrooms in their schools. In Canada we see a clear relationship between youth computer access and use and socioeconomic status in the home. As one study points out, about a third of the youth whose parents have no formal or only elementary school education have no computer in their home compared to 13 percent of those whose parent has completed high school (Looker and Thiessen 2003). In the 2000s, however, the prices for low-end computers dropped considerably, and it appeared the digital divide was ending. And while it is true that internet usage, even among those with low annual incomes, continues to grow, it would be overly simplistic to say that the digital divide has been completely resolved.

In fact, new data from the Pew Research Center (2011) suggest the emergence of a new divide. As technological devices gets smaller and more mobile, larger percentages of minority groups are using their phones to connect to the internet. In fact, about 50 percent of people in these minority groups connect to the web via such devices, whereas only one-third of whites do (Washington 2011). And while it might seem that the internet is the internet, regardless of how you get there, there is a notable difference. Tasks like updating a résumé or filling out a job application are much harder on a cell phone than on a wired computer in the home. As a result, the digital divide might not mean access to computers or the internet, but rather access to the kind of online technology that allows for empowerment, not just entertainment (Washington 2011).

Liff and Shepard (2004) found that although the gender digital divide has decreased in the sense of access to technology, it remained in the sense that women, who are accessing technology shaped primarily by male users, feel less confident in their internet skills and have less internet access at both work and home. Finally, Guillen and Suarez (2005) found that the global digital divide resulted from both the economic and sociopolitical characteristics of countries.