And the People Came

Scientific Theories - the Role of Linguistics

As you move through this course, you will examine some of the migration patterns, settlement patterns, and interactions of the First Nations and Inuit Peoples in North America, Canada and in Alberta. You will note that a number of sciences are involved in the efforts to unravel the mystery of the past. Linguistics is still being explored as being a crucial piece of the puzzle.

An article in the Smithsonian.com suggests that Ancient Migration Patterns to North America Are Hidden in Languages Spoken Today. (Click on the link to learn more.)

In reconstructing the ancient Beringian environment, the researchers provided a new clue that could help explain this discrepancy. They drilled into the Bering Sea between Siberia and Alaska and recovered sediment cores, and found that they contained plant fossils and pollen from a wooded ecosystem. Such an ecosystem, the authors argue, would have been an ideal place for humans to live. And with ice covering much of Alaska, the ancestors of Native Americans needn't have just strolled through Beringia, they suggested—they could have lived there for about 10,000 years before moving on.

In reconstructing the ancient Beringian environment, the researchers provided a new clue that could help explain this discrepancy. They drilled into the Bering Sea between Siberia and Alaska and recovered sediment cores, and found that they contained plant fossils and pollen from a wooded ecosystem. Such an ecosystem, the authors argue, would have been an ideal place for humans to live. And with ice covering much of Alaska, the ancestors of Native Americans needn't have just strolled through Beringia, they suggested—they could have lived there for about 10,000 years before moving on.

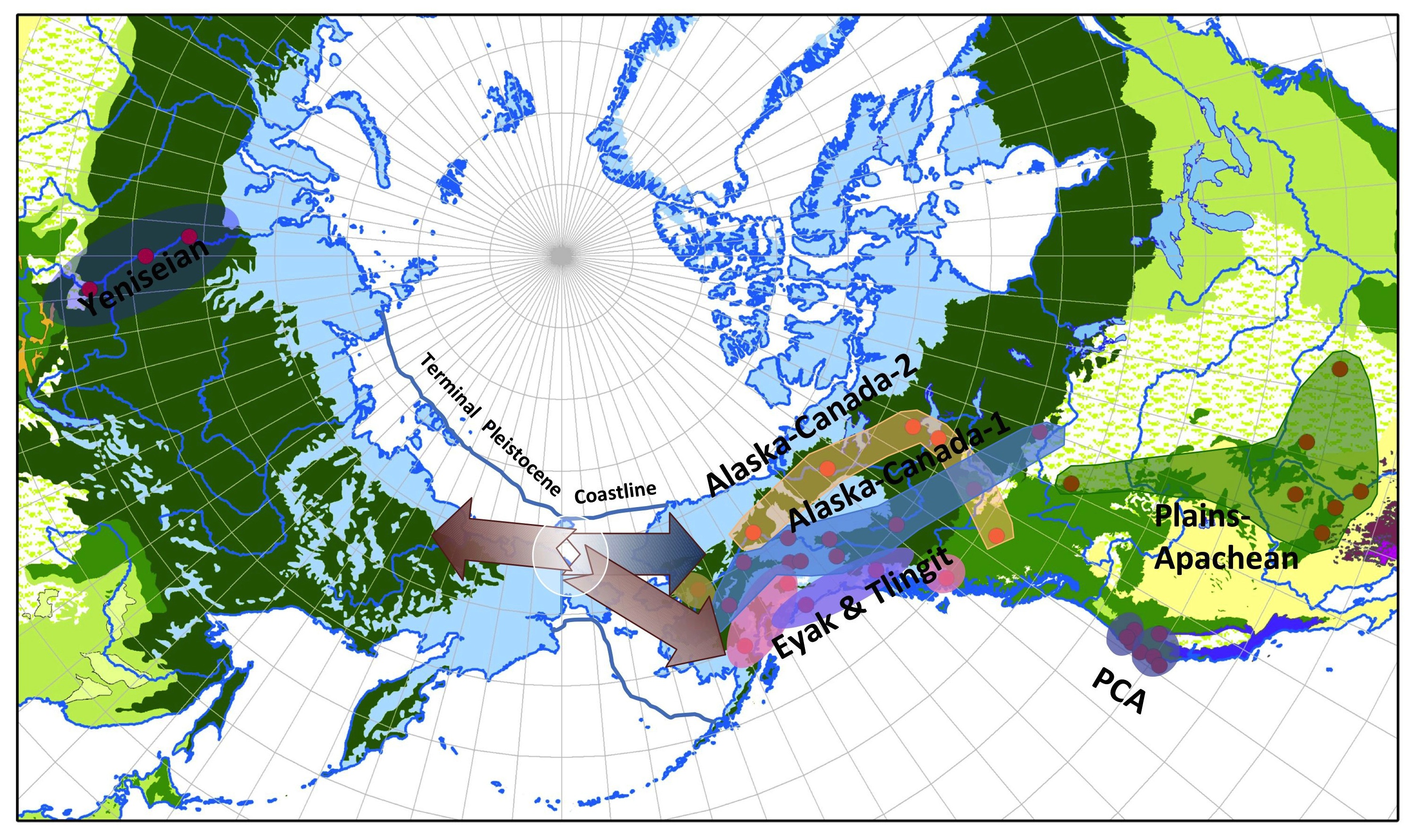

Now, more evidence for the idea comes from a seemingly unlikely source: languages still spoken in Asia and North America today. A pair of linguistics researchers, Mark Sicoli and Gary Holton, recently analyzed languages from North American Na-Dene family (traditionally spoken in Alaska, Canada and parts of the present-day U.S.) and the Asian Yeneseian family (spoken thousands of miles away, in central Siberia), using similarities and differences between the languages to construct a language family tree.

As they note in an article published today in PLOS ONE, they found that the two language families are indeed related—and both appear to descend from an ancestral language that can be traced to the Beringia region. Both Siberia and North America, it seems, were settled by the descendants of a community that lived in Beringia for some time. In other words, Sicoli says, "this makes it look like Beringia wasn't simply a bridge, but actually a homeland—a refuge, where people could build a life."