Northeastern Woodlands Culture

At the time of European contact in the fifteenth century, the peoples of the Great Lakes region were organised into well-defined political alliances. The Northern Algonquians had a looser organisation. The government of these Northeastern Woodland cultures functioned as a three-tier political system, consisting of the village council, national council, and the confederacy council. The main objective of this political system was to maintain communal harmony and ensure the subsistence of the people. A position of power and responsibility was achieved through consent rather than coercion. Therefore, no hierarchical-based central governing authority existed. Instead, groups banded together in political and social alliances. Annual meetings of the confederacy council strengthened economic and political ties. A village council, composed of all the leaders of a village, met daily. Discussions often carried on late into the night until council members reached a satisfactory agreement. The council body was made up of men, but required the approval of women. Chiefs were demoted if female elders deemed them unfit. Each clan was ruled by two different leaders, the civil chief and the war chief. The civil chief was chosen for qualities like intelligence, ability to speak for the group, generosity, and performance as a warrior. The civil leader was responsible for all local and domestic affairs, such as organising communal work tasks.

In the fifteenth century, the Iroquoians formed an alliance that was known as the League of Five Nations. Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Onandaga, and Seneca were the original nation members. The Tuscarora joined later and the political union became the Six Nations Confederacy. Each nation within the union had a set number of chiefs or sachems who attended the council. When one of the league's fifty chiefs died, the clan matron chose a successor in consultation with other women of her clan. If the person chosen proved unsatisfactory, his position as chief could be revoked by the clan mother. The Iroquois called this process "dehorning the chief" because the deer antlers that signified his office were taken away. Decisions were consensual and the chiefs had to agree to each as if they were of one heart, one mind, and one law. The league itself was symbolised by the longhouse, with the Mohawk guarding the east door, the Onondaga tending the hearth, and the Seneca guarding the west door. Flanking the Onondaga at the central hearth were the Cayuga on the south wall and the Oneida on the north. Although the Six Nations Confederacy was built on this philosophy of unity and collective decision making, each nation was ultimately free to take its own course of action.

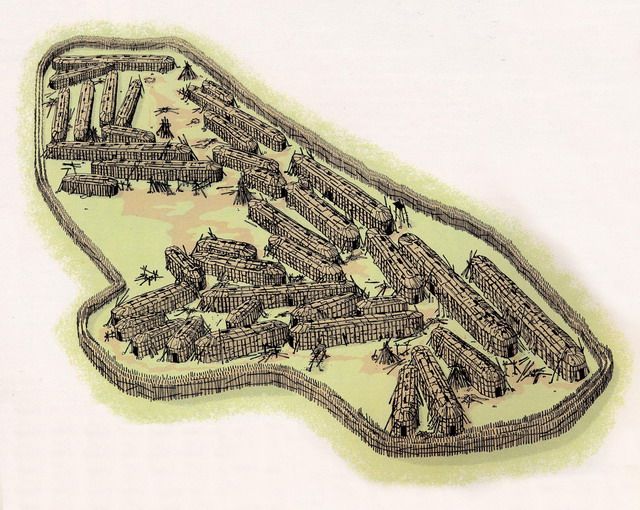

Warfare was open to negotiation within the nation and engaged only with the consensus of the elders. A family member killed in battle entitled the family to seek revenge on captured prisoners from the enemy band. Increased warfare also increased incidences of cannibalism and torture, which were carried out in ritualised ceremonies. Women and children captured in battle were adopted. Frequent warfare between the Iroquois and the Huron necessitated protection. The Huron built elaborate palisades (a fence made of wooden stakes) to help keep out their enemies. These palisades consisted of as many as three tightly-set rows of upright posts. Varying in height from five to eleven metres, these poles were often securely interlaced with branches and bark. At the top of the palisades, a balcony was positioned to provide space for warriors. From these balconies warriors could shoot arrows, drop rocks on those attempting to scale the walls, or throw water to extinguish fires set by the enemy.

Warfare was open to negotiation within the nation and engaged only with the consensus of the elders. A family member killed in battle entitled the family to seek revenge on captured prisoners from the enemy band. Increased warfare also increased incidences of cannibalism and torture, which were carried out in ritualised ceremonies. Women and children captured in battle were adopted. Frequent warfare between the Iroquois and the Huron necessitated protection. The Huron built elaborate palisades (a fence made of wooden stakes) to help keep out their enemies. These palisades consisted of as many as three tightly-set rows of upright posts. Varying in height from five to eleven metres, these poles were often securely interlaced with branches and bark. At the top of the palisades, a balcony was positioned to provide space for warriors. From these balconies warriors could shoot arrows, drop rocks on those attempting to scale the walls, or throw water to extinguish fires set by the enemy.

Semi-sedentary agricultural lifeways contributed to population increases, which did not occur because of increased food from trade, but rather local food diversity. Huron and Iroquois crop cultivation was so extensive that they operated as the granary for northern groups. Items bartered included corn, cornmeal, and tobacco in exchange for prime animal pelts and porcupine quills. In addition to direct trade with their allies and the Northern Algonquians, the Huron monopolised all the Petun or Tobacco nation's trading activities, acting as middlemen and profiting from the bartering activities. A monetary unit called wampum was made from coastal shell beads and was strung or woven into belts or collars. It was used for purchasing goods and was a symbol of wealth. Wampum held not only economic value but also spiritual power. Transportation routes are an important element in the trade networks, and a small number of families controlled the trade by controlling the routes, but wealth was distributed to maintain balance.