Great Plains Culture

At the time of initial European contact, the Plains buffalo culture had been established for thousands of years. Groups of extended families travelled together and joined seasonal camps for hunting, food gathering, and celebrations. These seasonal gatherings also served a social function. Plains peoples met for games and gambling, and they also renewed social ties. Councils and ceremonies were held for men's and women's societies. Women who were respected for their skills in crafts or hunting were consulted for their wisdom. Younger or less experienced women sought them as teachers and guides. The political leadership of these seasonal camps was based upon a system of consent. Family and peers considered each other primarily as equals and the leader held no power beyond influence. He was chosen because he was well respected within the community and because he was also an exceptional hunter. The Poundmaker was the winter village chief.

A unified armed force guarded against other bands killing bison within a given area. Peace negotiations were performed with ceremonial pipes, which solidified bonds or decisions. But if peaceful solutions failed, war was waged for territorial, political, and revenge issues. Conflicts on the Plains were common but there were few casualties. On the Plains war pits were dug so as to allow warriors to fight while under cover. Men were killed in battle, and enemy women and children were captured during warfare and adopted.

There developed a code of ritualised fighting, called "counting coup", which involved striking an enemy with a special stick. The game was judged on the degree of difficulty and danger a warrior faced when getting close enough to the enemy to actually land a blow. "Counting Coup" was also the term used to describe warriors recounting their exploits in battle. The greatest achievement for a warrior was stealing an enemy's weapons. Young males trying to establish their warrior status carried out raids on enemy camps. Men belonged to military warrior societies, which were formed around the image and character of an animal spirit. The wearer of the Buffalo headdress did not back down in battle. A headdress of feathers and scalps symbolised the defeat of an enemy in hand-to-hand combat and taking of the loser's scalp. A warrior with a headdress and scalp was entitled to marry and establish a household. A headdress that flowed down to the ground indicated that the wearer was a candidate for chief.

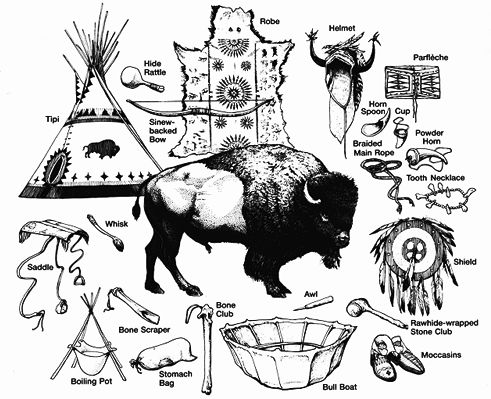

The Plains region was inhabited by as many as sixty million bison. The bison became the single most important animal to the Natives of the Plains, the primary source of meat in the Native diet and for raw material for manufactured goods. The bison provided food, shelter, clothing, containers, and tools. The bison's size and coat made it ideally adapted to the seasonal extremes of the Plains climate. Herds could locate grass under snow but they always left a small amount of grass so that it could replenish itself for the following season.

The Non-Food Products of the Buffalo

(Canada Historical Atlas)