Lesson 3 - Stereotypes, Labels, Sample Size, and Side Effects

Research Samples

Another problem with labelling involves sampling. Researchers in the late twentieth century designed experiments that focused on one subset of individuals and then assumed the results applied to everyone. For example, much research was done using Caucasian adult males. The results were then “carried over” or ascribed to women (who are not men), children (who are not adults), and men who were not Caucasian. Researchers discovered that the results could not simply be transferred to other demographic groups. How women, children, and other races respond to drugs, therapies, and other treatment methodologies is often different from how a Caucasian adult male responds. With psychological research, any study that uses only white males must ascribe any outcome only to white males, not to children, women, or other races. In some cases, a medication that is effective for an adult is ineffective for a child; in some cases it even has the opposite effect. In other cases, sometimes a smaller dose or larger dose of a medication has the same effect on a child that a standard adult dose has on an adult. Fortunately, current researchers take into account the fact that there are marked differences between adults, children, and adolescents in addition to men, women, and people of different races.

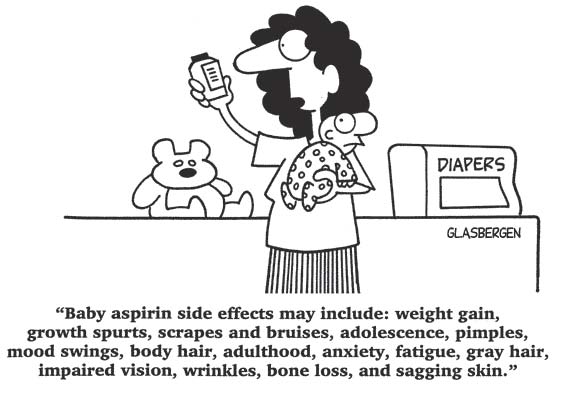

Not long ago scientists realized they lacked the necessary tools to properly diagnose children. Advances in this area are being made, but the long-term consequences of medication-based treatment have not been sufficiently documented. Many child psychologists note that non-pharmaceutical treatments can drastically reduce or even eliminate the need for medication in some children. Cognitive behavioural therapy, for example, helps children learn to manage their thoughts and control their behaviour. Some individuals, however, may need medications for the more debilitating symptoms despite side effects such as weight changes, jitteriness, or a dulled/flattened personality.

Not long ago scientists realized they lacked the necessary tools to properly diagnose children. Advances in this area are being made, but the long-term consequences of medication-based treatment have not been sufficiently documented. Many child psychologists note that non-pharmaceutical treatments can drastically reduce or even eliminate the need for medication in some children. Cognitive behavioural therapy, for example, helps children learn to manage their thoughts and control their behaviour. Some individuals, however, may need medications for the more debilitating symptoms despite side effects such as weight changes, jitteriness, or a dulled/flattened personality.

In studies published in the Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, kids with ADHD who exercised performed better on tests of attention, and had less impulsivity, even if they weren't taking stimulant medicines. Many kids with ADHD also struggle socially and with their behavior. Playing a sport can have the added benefits of improving both of these areas. (WebMD)

(http://www.webmd.com/add-adhd/childhood-adhd/exercise-for-children-with-adhd_?page=2)